Introduction

Radiation oncology (RO) is the medical specialty that provides radiotherapy (RT), i.e., the use of ionising radiation to destroy cancer cells1 and forms an integral part of the comprehensive treatment of cancers. RT may be indicated as an adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment, alongside other modalities including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, and surgery.2 RT is indicated for greater than 50% of patients during the course of their cancer illness and has also been associated with 40% of curative cancer outcomes.3,4 In addition to providing curative treatment for many cancers, RT is also indicated for the local control of primary malignancies, as part of palliative care for metastatic disease, and for the prevention of recurrence of certain cancers, either primarily or in conjunction with chemotherapy and surgical interventions.5

The National Cancer Strategic Framework for South Africa 2017–2022 (NCSF)6 was a seminal strategy that provided direction for public health sector cancer policy and services in the country. The NCSF identified five priority cancers, based on the burden of disease in South Africa, i.e., lung, colorectal, cervical, prostate, and breast cancer. These five cancers accounted for just over a third of the cancers reported in South African in 2014 (36.9%; n = 27 496).7 Additionally, cancers of childhood, adolescence and young adulthood were included as a sixth national priority. The NCSF recommended integrative strategies for cancer control and described the availability of cancer services for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancers within the South African public health sector. The strategy also recognised the importance of strengthening RO treatment facilities given the unmet demand especially for RT, with related crises in a few provinces, and suggested significant areas for prioritised attention.7 There was, however, little strategic focus on the different treatment modalities and services, including RT provision, despite their havin been under the spotlight regularly in the previous decade due to inadequate access to RT in various provinces.8–12

In the South African public health sector, there are pervading challenges with equitable and timeous access to RT, depending on the type of cancer being treated.13 Public health services for the commencement and continuation of RO care have been constrained by various factors including variations in service coverage, lack of adequate equipment or related failure with regard to maintenance, and shortages of specialised human resources, including insufficient radiation oncologists, medical physicists, radiotherapists, planning radiotherapists, and nurses, all of whom are essential for ensuring proper access, efficacy, quality and safety of RT.14 Appropriate access to effective RT also requires the availability of sufficient medical, surgical, radiological, pathologic, and RT infrastructure, i.e., localising systems (computed tomography (CT) simulators), radiotherapy planning equipment and software, and radiotherapy treatment machines (e.g., linear accelerators).15

With an indisputable background disparity between the demand for and the supply of RT services within the South African public health sector, this article provides insights into the role of RT as a modality of cancer management within the South African context and applies a futurist approach, i.e., causal layered analysis (CLA), to interrogate issues related to access to RT from different perspectives in order to propose recommendations to strengthen RO services and improve access to RT for patients diagnosed with cancer in South Africa.

Methods

As a futurist theory and methodology, CLA provides a unique approach to explore the multifaceted factors and perceptions that influence access to RO services, presenting an opportunity to engage at a deeper level with alternative futures than some more traditional methodologies. The NCSF, relevant literature, and expert perspectives were used to explore the multiple levels of influence related to RO services in South Africa. In line with CLA, the first level of analysis considered was the litany, which described current scenarios in context, while the second layer deconstructed systemic issues that contribute to the litany. The third level delved deeper to understand the worldview that contributes to the systemic picture and reinforces the RO litany in the country. This enabled the identification of pervading perceptions behind the issues, so as to identify alternate scenarios that might inform future planning. The final layer of analysis explored myths, i.e., conscious and unconscious assumptions that are at the root of the worldview.16–18 The four CLA layers were used to explore RT services in South Africa and to make recommendations to address gaps in service provision.

Causal Layered Analysis

Litany

This level considers the current context of cancer diagnoses and public sector RO services in South Africa, including the burden of disease, indications for RT, and RO services within the public health sector.

Burden of disease

Cancer has been reported to be the leading cause of death globally, with greater than 70% of deaths occurring in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In South Africa, neoplasms (cancers and benign tumours) were the fourth leading cause of death in 2018, accounting for 9.7% of all mortality in the country.19

Table 1 lists the ten leading cancer diagnoses reported in South Africa in 2019, which together accounted for 80% (n = 68 367) of the total reported diagnoses. The five priority cancers from the NCSF represent approximately half of these cancers, i.e., 40.6% (n = 34 720).19 The most common cancers among females in the country included basal cell carcinoma of the skin (17.9%), breast cancer (12.1%), and cervical cancer (8.1%).20 Among males, the most frequently diagnosed cancer was prostate cancer (12.3%).20

Indications for radiotherapy

When considering management approaches for the ten leading cancer presentations in South Africa, RT may be indicated for the majority (72.46-80%) of cases (Table 1). With the understanding that these are high-level considerations and subject to RO evaluation and individual patient treatment plans, RT should form part of optimal cancer management in the following instances20:

-

RT can be considered for all stages of all skin cancers. Surgical resection is generally the primary method of treatment for early stages, but there may be indications for post-operative RT (e.g., positive margins). RT may also be offered upfront as a primary treatment modality, even in early stages (e.g., if cosmesis is thought to be better, or if adequate surgical margins or reconstruction will not be achievable). In metastatic disease, RT may be used for palliation, e.g., for bleeding or pain, from metastases or the primary cancer, or in RO emergencies (e.g., spinal cord compression).

-

RT is a treatment option for early-stage prostate cancer. In early-stage patients, one may choose between radical prostatectomy, prostate brachytherapy (internal RT), external beam RT (EBRT), or possibly active surveillance, in some instances. Locally advanced prostate cancer almost always requires RT (external beam RT with or without brachytherapy and androgen deprivation therapy). Oligometastatic (stage IV) cancer may still require local therapy. EBRT +/- stereotactic radiosurgery can be considered for oligometastatic disease in addition to androgen deprivation or other systemic therapies. In widespread metastatic disease, EBRT plays a mainly palliative role.

-

RT is indicated for early-stage breast cancer, post breast-conserving surgery. More advanced breast cancer may require RT even if a mastectomy is performed. RT in metastatic (stage IV) disease is used for palliation (e.g., brain metastases, bone pain), or for RO emergencies (e.g., spinal cord compression).

-

In very early-stage cervical cancer, surgical resection (e.g., radical hysterectomy) is preferred. RT may still be necessary if high-risk features are seen (e.g., close/positive margins, positive lymph nodes, etc.) on the post-operative histology specimen. Most cervical cancers from FIGO stage II upwards require definitive RT or chemoradiation therapy (chemoRT) as their primary management and when surgery is not appropriate. In metastatic (stage IV) disease, RT may be used to palliate local symptoms (e.g., pain, bleeding), or in emergencies (e.g., acute spinal cord compression).

-

Neo-adjuvant pelvic RT is indicated in most cases of locally advanced rectal cancers. In early-stage rectal cancer, it may be required as an adjuvant to upfront surgery if there is an indication (e.g., positive lymph nodes). It is used mainly as palliation in metastatic (stage IV) rectal cancer. The role of RT in colon cancer is mainly palliative.

-

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for early-stage (stage I and II) lung cancer. In medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer, stereotactic radiosurgery may be considered as an alternative to lobectomy. In locally advanced (stage IIIB) lung cancer, chemoRT is the standard of care. In metastatic disease (stage IV), systemic therapy is usually indicated and the role of RT is mainly palliative.

-

RT is sometimes required after an inadequate response to primary chemotherapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or sometimes for bulky disease at presentation.

-

There is a limited role for RT in the management of melanomas. RT may occasionally be needed as an adjuvant to surgical resection. In metastatic disease, it plays a palliative role.

-

Primary chemoRT is the treatment of choice for locally advanced squamous cell or adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. In locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus, definitive chemoRT can also be considered. In metastatic disease, it can be used to palliate local symptoms (especially obstruction or bleeding), or to treat oncologic emergencies such as a spinal cord compression.

-

Radiotherapy is used as an adjuvant to total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in certain cases of uterine cancer (e.g., high grade of tumour or positive margins). In patients who are inoperable but do not have metastatic disease at presentation, definitive RT can be used as a treatment modality. In metastatic disease, RT plays a role in the palliation of local symptoms or in oncologic emergencies (e.g., spinal cord compression).

-

Radiotherapy can be used in patients with Kaposi sarcoma who are refractory to chemotherapy. It can also be used in localised disease on a case-by-case basis.

-

Definitive chemoRT is a treatment option for patients with bladder cancer who have good bladder and renal function and are inoperable or refuse a radical cystectomy. Patients often choose the option for chemoRT due to the morbidity associated with a radical cystectomy. In metastatic bladder cancer, RT is mainly used for palliation or to treat RO emergencies.

Access to RO services in South Africa

Access to RO services in South Africa is inequitable and dependent on factors including urban or rural location, public or private healthcare sector, and socioeconomic status. Within the public health sector, dedicated RO departments are primarily located at tertiary or central hospitals, which are found in major cities and provinces. Limited RO services are situated at a few regional hospitals. Due to the increasing incidence of cancer diagnoses, there is a high demand for the limited supply of services, and consequently waiting times for RT in the public sector range from weeks to even years. In 2021, waiting times to receive RT in Gauteng were reported to be up to five years for patients with prostate cancer, up to a year for patients with breast cancer, up to six months for patients with cervical cancer, and between two to four weeks for terminally ill patients requiring palliative care for immediate support and pain relief.10 Such delays with access to RT are not unique to Gauteng and can be found at many public sector RO units in South Africa.9

Consideration of the litany and proximal issues related to access to RO services in South Africa highlights the visible symptoms of the problem, including the burden of cancer, the indications for RT, and currently available RO services within the public health sector. This forms the basis for deeper exploration.

Systemic causes of decreased access to RT

Given the challenge of access to RO services within the South African public health sector, the second layer of CLA examined the systemic issues that contribute to the suboptimal availability and variable implementation of RO services across the country. Despite ongoing efforts to improve access to RT services, including enhanced strategic focus, the establishment of new centres, increasing training opportunities for radiation oncologists, and initiatives to address disparities in rural areas,6 equitable access to RO services remains restricted. At the systemic CLA level, the pathway for access to RT was mapped, following which the fundamental health system building blocks for RO services were reflected on in order to identify potential systemic solutions.

Patient pathway to access RO services

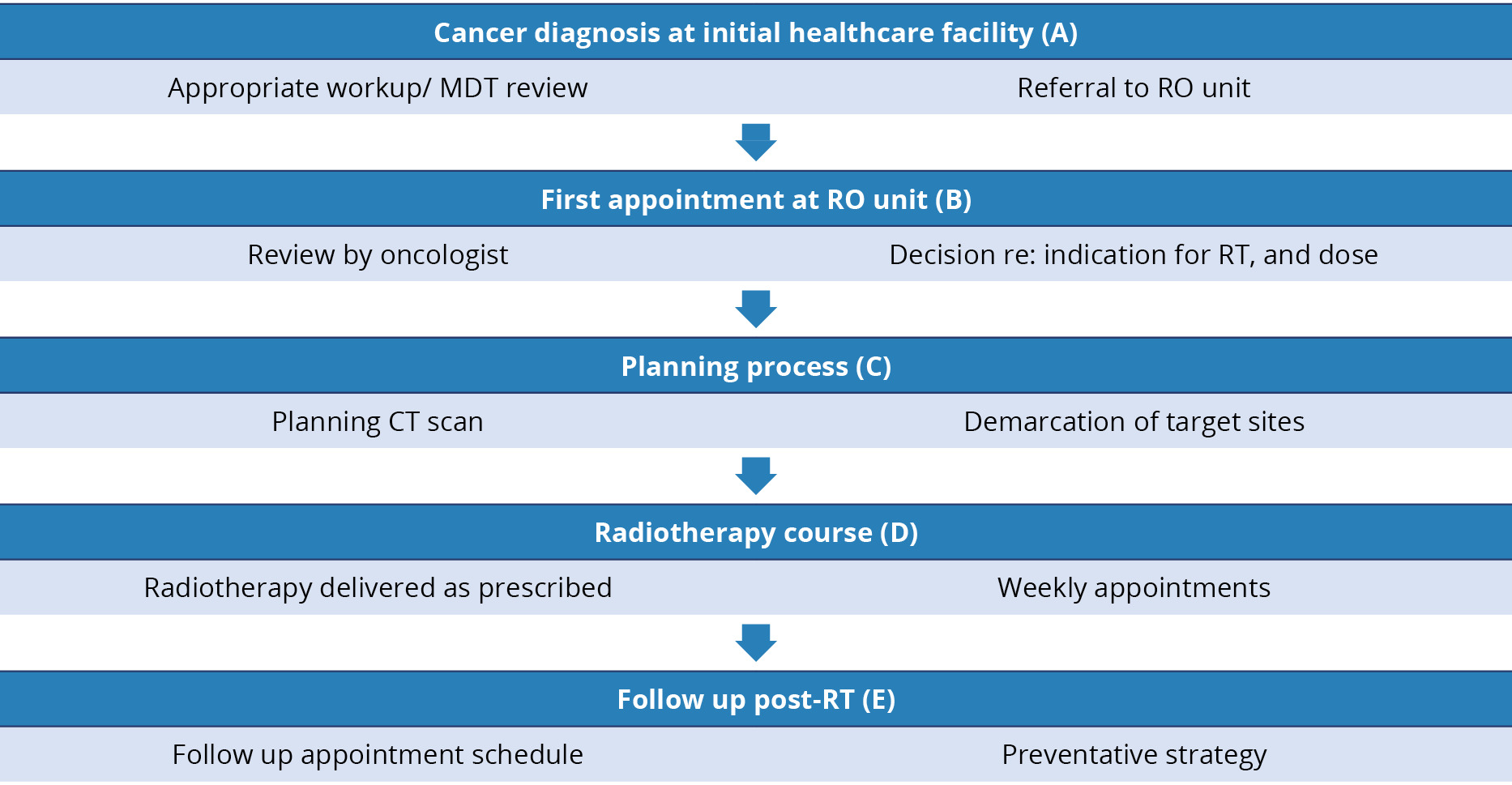

Once diagnosed with a cancer where RT may be indicated, a patient should ideally be discussed by a multidisciplinary tumour (MDT) board. If RT is required, then the patient should be referred to a specialist centre for their initial consult with an oncologist. If no MDT exists at the referring unit, patients may be referred to oncologists at an RO centre for assessment and decision-making regarding RT. However, if additional tests are required, the patient may be referred to the original referring site to have these done, potentially increasing the time to initiation of RT. When an oncologist determines or confirms that RT is indicated, the patient is referred for RT planning, which includes a radiation planning CT scan and subsequent determination of the individual’s RT plan. In extremely busy and/or understaffed public sector RT units, the RT planning process can take up to two months to complete and, only once completed, can RT commence. Once the course of radiation is completed, a follow-up appointment is scheduled to monitor outcomes. Figure 1 shows the typical journey of a patient through tertiary level RO services.21

Knowledge of all processes related to accessing RO services within the public health sector allows for focussed attention and optimisation of implementation. Early areas to reinforce (A, B) include ensuring the availability of protocols at both the RO unit and referral facilities. These include information on the RO service delivery platform, i.e., referral pathways, referral criteria regarding cancer types and treatment options, descriptions of the full workup required for a patient to be comprehensively assessed at the first consult with RO, an overview of appointment systems, the various reporting requirements, as well as platforms for bi-directional feedback. Additionally, guidelines for MDT reviews at referral facilities would further enhance RO processes and patient experiences.

The RT planning process uses various imaging approaches to identify the cancers and select appropriate RT options for the patient that aim to deliver an adequate dose to the tumour while minimising RT exposure to surrounding tissues.2

Attention to this process (C), including forecasting the demand for planning CT scans at an RO unit, and identifying opportunities for streamlining the treatment planning process, would also decrease overall waiting times for RT. A current pilot project at a central hospital RO unit is investigating the feasibility of using artificial intelligence to generate patients’ RT plans, with hybrid offsite radiotherapy planners and an artificial intelligence neural network.22 This has the potential to address certain contextual challenges, including shortages of trained staff as well as reducing waiting times for RT.

Consideration of alternative RT dosing strategies (D) using evidence-based, shorter treatment regimens, may also benefit the individual patient as well as improve the capacity of the RO system to allow more patients to access treatment. The choice of regimen depends on various factors related to the tumour, the patient’s general health status, treatment goals, and alternatives to the standard RT dosing regimen, i.e., conventional fractionation (usually delivered once daily over several weeks, five days a week). These alternatives might include hypofractionation (larger doses of radiation per fraction over a shorter treatment period), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), i.e., a highly precise form of RT that delivers very high doses of radiation in a few fractions, or accelerated fractionation (delivering the total prescribed dose in a shorter overall treatment time by increasing the number of fractions per day or by treating twice daily).2

Health system considerations

Appropriate structural requirements at all levels of the health system need to be in place to support optimal RT access and patient flow. Table 2 considers these from a health systems’ perspective and proposes solutions for pervading constraints.

The systemic causal layer delved deeper to examine structural and organisational factors and identified systemic barriers to accessing RO services and RT, i.e., the root causes of the surface-level issues described at the litany level. Areas that offer future solutions relate to enhancing clinical governance for improved patient experiences, and health systems strengthening to support sustainable provision of RO care.

Worldview

The third CLA level sought to understand the worldview that reinforces the RO litany in South Africa, in order to identify pervading perceptions from different stakeholder perspectives. South Africa is signatory to the UN resolution on Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,23 whereby countries committed to adopting an integrated approach to cancer prevention and control. Additionally, the Ministerial Advisory Committee on the Prevention and Control of Cancer (MACC) was established in 2013, which convened diverse stakeholders committed to cancer care and who were critical in the adoption of the NCSF. The global and local high-level commitments to improving cancer prevention, treatment, and control create a positive environment for planning appropriate services in the country. This is supported by the NCSF; however, the translation of policy to practice and improved patient outcomes across the country is variable and RO services have been in the public spotlight due to inadequate provision of adequate care for cancer patients, including access to RT.

In June 2017, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) released a report following investigations related to a complaint about the inadequate provision of RO services in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) public health sector. The investigation determined that the respondents (Addington Hospital, Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central (IALC) Hospital, the Department of Health KZN, and the MEC of Health in KZN) had “violated the rights of oncology patients at the Addington and IALC Hospitals to have access to healthcare services as a result of their failure to comply with applicable norms and standards set out in legislation and policies.”11 This was found to be related to staff shortages and non-functioning equipment. The Commission recommended that the respondents took immediate steps to address the issues related to equipment, and that a plan to address the backlog of access to treatment of cancer be implemented.11 The recommendations included the development of public-private partnerships for screening, diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

In response to provincial legislature queries in May 2021, the Gauteng Department of Health MEC revealed that the cancer unit at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Hospital was short-staffed, was frequently out of stock of chemotherapy drugs, and had broken and outdated radiation machines.9 Apparently, the unit had a deficit of 71 out of 175 required staff, including 16 specialist oncologists, 15 radiation therapists, nine specialists in training, nine medical physics interns, six registered nurses, five staff nurses, three oncology trained pharmacists, two medical registrars and two medical officers.8 In November 2021, health activists from the Cancer Alliance, the Treatment Action Campaign, and SECTION27 led a march to highlight the dire state of cancer services in Gauteng and to demand that the Premier urgently address the crisis in the province.9

These diverse vantage points have a common purpose, i.e., to improve access to cancer services, including RT, for patients in South Africa and should be leveraged to create a momentum for change and drive significant improvements in cancer care and RT services in the country. Active stakeholder engagement with government officials, healthcare professionals, private providers, patient advocacy groups, civil society organisations, and donor organisations to discuss the challenges with cancer care and RT services could foster novel approaches and meaningful collaborations to develop comprehensive solutions. Additionally, educational initiatives via media campaigns and public forums to inform the public about promotive and preventive approaches to cancer control, as well as the challenges faced and the need for improved RT services, could all have a positive impact on cancer care and patient outcomes.

The worldview layer considered high-level commitments, stakeholder perspectives, and societal perceptions about cancer policies and practices that shape attitudes towards RO services in South Africa. Despite longstanding high-level commitment to the provision of optimal cancer services in the country, there are serious gaps in the provision of RT in the South African public sector.

Myths

The final layer of analysis questions myths which, in this context, refer to commonly held beliefs or misconceptions regarding RO services in South Africa. These may be conscious or unconscious beliefs at the root of the worldview and are crucial to address and provide accurate information about perceptions of RO services.

The first myth considered is that RT is used as a last resort when other treatments fail; however, in reality, RT is often used as the primary treatment for cancer, alone or in combination with other modalities of treatment. It is also indicated for the management of the majority of commonly occurring cancers and may be used at various stages of disease, depending on the cancer type.3,4

Another myth within the media is that the silver bullet to solve the crises related to cancer treatments is ensuring that more radiation oncologists are employed. Various media headlines alluding to this include: “The state of cancer services: Are oncologists a dying breed in SA”,24 “Cancer crisis: Where are South Africa’s radiation oncologists?”,24 and “Limpopo: 0. Mpumalanga: 0. That’s how many radiation oncologists these provinces have”.11 Despite this cadre of staff being a crucial component of RO services, it is important to understand that for RO services to function, in addition to radiation oncologists, various other staff categories are also required, including RO nurses, RT technicians, medical physicists, etc. Additionally, appropriate infrastructure, better service coverage, and enhanced coordination of RO services is critical to meet the demand for care. Thus, the business case for RO service provision is vital to inform appropriate planning and adequate staffing.

This final layer examined assumptions and misconceptions associated with RO services in South Africa in order to understand the narratives shaping public discourse, and to challenge prevailing myths and offer alternative approaches to inform policy and practice.

Conclusion

Using CLA to explore the different aspects of RO services provided an optimal framework to consider the multidimensional factors that impact access to care. RT is indicated in the management of the majority of cancer diagnoses and stages in South Africa; thus, it is imperative to improve access to RO services within the public health sector. Mapping of the continuum of care and RT processes, as well as identification of barriers at each stage, served to identify important areas to address to improve future cancer care. Consideration of existing public health sector RO services from the health system perspective further highlighted strategies that could strengthen RO services. A key consideration for RO provision in South Africa is articulation of the related business case. Relatedly, comprehensive policies, improving provisions at all levels and locations, enhancing coordination of care, continual stakeholder engagement, and advocacy for policy reforms, including lobbying for increased funding, improved infrastructure, improved workforce planning, and the development of comprehensive cancer care strategies, could all lead to sustainable improvements in access to RT and overall cancer care in South Africa.