Introduction

Similar to many parts of the world, cancer is emerging as a critical public health problem in South Africa (SA).1 Advanced-stage diagnosis of cancer among SA communities relying on public healthcare services is mainly associated with the patient- and health systems-related barriers to care.2,3 Lung cancer patients in SA are bearing the effect of not only the disease but also the health systems.4,5 SA’s mortality rate of lung cancer has been reported at 13.4%, ranking highest among all cancers.1 This burden is aggravated by patients’ and healthcare providers’ low suspicion index, limited financial and human resources, poorly developed healthcare systems, and limited quality care.2,6–8

Cancer management is complex as it requires multi-specialty investigations, treatment rounds, and follow-ups.2,4,9–11 Care involves multiple transfers between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and settings where critical information must be effectively communicated.4,12,13 With so many HCP services and geographical settings involved, the care of these patients can become fragmented and uncoordinated, with patients in distant and underserved areas being the worst affected, given that cancer care typically requires travel to distant healthcare facilities.4,8,14,15 Arising from the complexities of cancer care, effective care coordination is needed to ensure all patients receive timely, appropriate, and equitable care to maximise the improvement of their experiences and health outcomes.

SA has parallel and highly unequal private and public healthcare systems operating in tandem, where most of the population, over 70%, depend on the public healthcare system for care.16–18 Conversely, an estimated 80% of doctors work in the private system, serving only about 20% of the population.18 The public health sector’s structure is based on a strict referral system6,12 that needs to be revised and better managed.19 It is divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary health services provided through various health facilities.18,20 These levels of healthcare can be thought of as a pyramid going from less specialised at the bottom to more specialised healthcare at the top (Figure 1).

Primary care facilities are meant to be the first point of contact for patients and provide an initial assessment of the patient. At this level, doctors and primary healthcare nurses deliver most care.20 The next layer comprises the district hospitals with general practitioners (GPs) and clinical nurses.20 Following that are regional hospitals that serve patients based on referrals from district hospitals and usually have 200-800 beds.20 Between the regional and central hospitals are tertiary hospitals, which generally operate through referrals from the regional hospitals. These facilities provide supervised specialist and intensive care services. Central hospitals are at the top of the pyramidal referral pathway and offer an environment for multi-specialty clinical services, innovation, and research. This system influences how the transition occurs and whether critical information is effectively shared.18 In a well-functioning health system, patients are matched up with the right level of care, so only those who need the more specialised services access them.

While patients with lung cancer initially contact primary care as their first point of care, they often transition between appointments from primary to tertiary and specialty care providers. They are particularly at risk of receiving poorly organised and fragmented care due to the complex nature of the disease and its management.2,3,7,13,21 To be comprehensive, cancer care must be coordinated between HCPs. However, achieving this has proven considerably challenging.3,4,22–25 The high inconsistency of practices and the diversity of definitions and underlying concepts increases the difficulty of standardising, replicating, transposing, and assessing care coordination, especially within the context of South African health systems.4,6,7,10,11 Recognising the importance of coordination and gaps in cancer care in SA, it is essential to investigate stakeholders’ perspectives on the multi-level barriers that threaten care coordination across different settings, levels, and services.

An essential step toward improving health outcomes for cancer care is identifying and analysing barriers to effective coordination from the perspectives of those involved in receiving and providing healthcare.26 As such, this paper explores HCPs’ views on issues related to the coordination of lung cancer care among the various levels of care.

Methods

Study design

The study draws from a grounded theory (GT) design in exploring HCPs’ perspectives, practices, and experiences in cancer care coordination. This comprehensive qualitative research methodology is particularly suitable when the research aims to explain a process centred on the concerns of those involved, which cannot be predetermined.27 Owing to the challenges imposed by COVID-19, some in-depth interviews were conducted virtually, but face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted when it was permissible to do so. In-depth interviews enabled a rich exploration of the phenomenon from the perspectives of the HCPs.

Study area and settings

This study was conducted in the province of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), SA. Clinics and hospitals in Durban communities and Pietermaritzburg within the province were selected as study sites. The communities were: Umlazi, Chatsworth, South Durban Basin, Cator Manor in Durban, Imbali, and Sobantu in Pietermaritzburg. Primary clinics to tertiary hospitals were included in the study to ensure that the data captured diverse insights from a broad spectrum of cancer care HCPs. The facilities comprised: Prince Mshiyeni Memorial Hospital, RK Khan Hospital, two Umlazi clinics, and Sobantu clinic. Furthermore, all three public hospitals (Greys Hospital, Addington Hospital, and Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital) with oncology units in KZN were recruited to participate in the study.

Study population and sampling

The study population encompassed HCPs drawn from the participating healthcare facilities, including pulmonologists, radio-oncologists, medical oncologists, GPs, nurse practitioners, social workers, and dieticians, all of whom had some experience and/or involvement in coordinating care activities for patients living with cancer. Purposive sampling was used to initiate participants’ selection and to ensure that participating HCPs had diverse views and experiences in cancer care coordination. The targeted potential participants were those with extensive experience in the care of patients living with lung cancer across various healthcare settings and disciplines. To identify and follow clues from the analysis, fill gaps, and clarify uncertainties, the initial purposive sampling was followed by theoretical sampling, which continued until saturation was reached.28

Ethical considerations

Before participant recruitment and data collection started, ethics approval was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC). Furthermore, gatekeeper permission and site permissions were obtained from the KZN Department of Health and participating health facilities, respectively. All potential participants signed informed consent before being interviewed. Existing professional networks assisted in consolidating the list of all potential participants across all the facilities participating in the study.

Data collection and sample size

Participant interviews took place from June 2021 to December 2022 at locations/platforms and times suitable for participants, and all COVID-19 precautions were taken in accordance with prevailing regulations. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions and probes was used to deepen understanding of care coordination. The topics covered centred on coordination, the interface between the different levels of care approaches used in the participants’ disciplines and the hospital, and their understanding, practices, and aspects affecting interdisciplinary collaboration and coordination in caring for cancer patients. Participants were later asked to recommend strategies to improve continuous and coordinated cancer care delivery in public health facilities. Data saturation was reached at 29 in-depth interviews, with three being repeat interviews (for further probing), bringing the total number of participants to 26 across eight health facilities. The average interview duration was 47 minutes across HCPs at all levels of care.

Data management and analysis

Concurrent data generation and analysis are fundamental to GT research design.28 Therefore, data generation, coding, and analysis were done iteratively. Theoretical sensitivity encompassed the entire research process, enabling the identification of data segments important to the development of the theory and thereby directing the ongoing data generation.28 Interview recordings were de-identified, transcribed by a professional and experienced transcriber, and imported into NVivo for data management and to facilitate analysis. No fixed theory was used before data analysis. The first author analysed the content of each interview, as recorded in both tapes and notes. Finally, this data was sorted into four themes. The construction process of these thematic categories and coding was hybrid, drawing from both inductive and deductive approaches because the development of themes and subthemes rested on literature and emerging categories of the empirical analysis. Ongoing analysis and recruitment continued until saturation of themes was reached. Lastly, all the authors discussed themes to reach a consensus. Direct quotes from participants are used to support the interpretations of the findings.

Findings

Participants’ characteristics

Most (77%) participants were female. Participants included four radiotherapists, four professional nurses, three pulmonologists, three oncologists, three social workers, two oncology nurses, two medical officers, one physiotherapist, a dietician, a speech therapist, and a GP (Table 1). Seventy-three percent of HCPs ranged between 30 and 49 years of age, with the remaining 27% being 50 years and above. Most (62%) HCPs were from tertiary or specialty care.

In the following sections, the presentation of results is divided into four main thematic areas, namely: (i) understated notions of care coordination; (ii) cracks in the organisation among entities of the public healthcare system; (iii) inefficiencies in written communication disrupting continuity of care, and; (iv) opportunities for enhanced care coordination. Primarily, the study wanted to know what the term ‘coordination’ meant to HCPs in the context of cancer care. The interviewed HCPs had various opinions on what coordination encompasses. Nevertheless, care coordination was primarily defined as relevant information transferred between providers and settings and was agreed to be crucial if a patient is to receive consistent and cohesive care. The narratives contained below reveal additional insight.

Understated notions of care coordination

While the need for care coordination is clear, obstacles within the KZN public healthcare system must be overcome to provide this type of care (HCP02-09, 12-14, and 17-26). One challenge encountered throughout the care coordination notion was the difficulty relating not just to understanding what coordination is but the need for more emphasis on coordinated patient care in the public health sector (HCP02-08, 12, 14, 23, 25, and 26). Primary and secondary HCPs recognised that redesigning and establishing a healthcare system that supports and emphasises the coordination of patients’ care is essential (HCP12, 20-23, 25 and 26).

Inadequate public service and working conditions

With most HCPs, inadequate coordination across the care levels in their networks emerged as they shared their experiences (HCP02-09, 12-14, and 17-26). Underlying most challenges is the increasing pressure on the HCPs within the public sector (HCP01-26). Participants asserted that the growing number of patients accessing cancer services limits the care and support that HCPs can provide to their patients (HCP05, 08-10, 12, 20-22, 25, and 26). Provider fatigue and burnout permeated through various interviews as an overarching phenomenon in healthcare facilities (HCP02, 04, 06-08, 13, 15, 21, and 26). Health professionals were of the view that the healthcare system was not designed in a manner that enabled them to provide organised and consistent patient care.

Primary care clinics experience high patient volume, often resulting in scheduling backlogs for existing patients and prolonged delays for new patients (HCP08, 12, 20, 25, and 26). This overcrowding is reportedly negatively affecting HCPs’ performance and patient health outcomes. Tertiary HCPs echoed this sentiment (HCP03, 14, 15, 17, and 18), saying that when a patient has endured a long wait or their diagnosis journey has not gone well, they experience long-lasting trauma that never goes away. “I spend more time with patients trying to reassure them and build trust in the system,” said an oncologist (HCP15). This statement is testimony to the damage the delays can create, culminating in patients losing confidence in the system. More than deploying additional resources, a patient-centred approach requires priority for implementing coordinated patient care, as asserted by about one-third of the participants (HCP05, 07-10, 13, 17, 20, 25, and 26).

As a service provider in the public sector, we do not have enough resources to offer to patients, so the perception says public service or public health in SA do not provide good services. Therefore, I think for us, is to try and improve the service to the public, there should be more efficiency so that when the patients come, we minimise their stay at the hospital, and we try and help the patient as soon as possible so that they do not wait. (HCP17)

Furthermore, the HCPs emphasised the importance of having enough time to help the patients identify and express their needs and explore their self-care abilities, which may be constrained by high patient volume. While the tertiary health level was said to be well-established and reasonably resourced, patients’ health outcomes and experiences still need improvement (HCP02, 06-08, 15, 21, and 25). HCPs concluded that resources are not rationally distributed, and healthcare delivery needs to be coordinated (HCP02-09, 12-14, and 17-26).

Patients’ lack of understanding of the healthcare structure

The problem of uncoordinated cancer care is not solely attributable to limited resources but also systemic issues resulting from gaps in knowledge of systems and structures of care in SA (HCP01, 13, 17, and 23). An aspect perceived as facilitating good coordination among the HCPs was the patients’ knowledge about the work of HCPs and care levels in the system. The South African healthcare system is organised around a strict referral structure, for which patients are often unclear about why they are being referred from primary care to a specialist, how to make appointments, and what to do after seeing a specialist (HCP01, 13, 17, 18 and 21-23). All participants emphasised the need for all stakeholders to understand the healthcare systems for effective patient care coordination (HCP 1-26). One participant suggested that people in communities should be educated on the systems and structures of healthcare, especially relating to the public health system and design:

We need community caregivers, and we do not need those people alone, but there are those retired nurses who can still work if the government could employ such people to educate communities and do home visits… Educate them because it is of no use for me to educate somebody at Albert [tertiary level] already requiring help. If I send him back to the base hospital, it is like you are neglecting him. (HCP13)

Moreover, patients should be provided with written care pathways of what to expect along their care management (HCP04, 06, 21, and 25). A physician shared: “When we refer them back to base hospitals, it is like you are denying them treatment and their life, whereas you are trying to correct, you know” (HCP19). From this statement, it is evident that the healthcare system frustrates not only patients but also healthcare professionals. One oncology nurse asserted:

So now they end up totally believing in us [tertiary level]. Even when they have minor alignments, they do not want to go to their base hospitals because they understand that these people [primary care providers] do not know; only we at Luthuli [specialty care providers] know. This then ends up disturbing the entire structure, we are overworked, and it becomes a mess. (HCP16)

Cracks in the organisation between entities of the public healthcare system

Non-standardised transitioning management

Participants reported an overall lack of integration and poorly designed referral systems, which they asserted could be more cohesive, and also that processes vary among and between primary and specialty care sites (HCP01-26). Participants considered the development of a strategy for a standardised care referral approach across all HCPs and facilities as essential, including providing a complete medical history with the referral (HCP01-26), as shared below:

… for different levels of care, we have not seen anything about cancer care protocol; we assume, not necessarily assume, we just do what people have been doing. You do things because that is how things have always been done, but I have never seen a clear protocol that is written down, yah [yes]. (HCP15)

Furthermore, participants recommended improvements to the current hospital administrative processes, especially concerning communication, continuity, and care coordination between services (HCP01-19, 22, and 24).

Lack of interoperability across healthcare services

Interoperability is crucial for seamless data transfer between healthcare systems and patient care delivery. Still, HCPs across the care spectrum reported a need for an effective referral system between services and health facilities, particularly from tertiary hospitals of specialty back to the local primary services from which patients sought support (HCP01-26). Most HCPs viewed systemic failures as placing the burden of coordinating care onto patients (HCP01-07, 10-11, 13-21, and 24). One oncologist (HCP07) admitted that she often relied on patients to communicate about their care management:

The other problem is that we as nurses can do our best, but if the other departments, like the pharmacy, say no, I am closing at 13:00, it compromises whatever good work you have done. So, the problem is, there is quite a number of us who are involved, but yet disjointed and … yah [sighs] it is hard. (HCP13)

In addition to the above results, several primary and tertiary care professionals also spoke of barriers, such as hospitals working in isolation (HCP03, 04, 06, 07, 10, 17, 21, and 24), essentially everyone working in their own ‘corner’ trying to service their part. While one tertiary hospital developed an effective electronic information system to facilitate information transfer among care providers, communication with systems outside this facility remains difficult. Some participants saw the inflexibility of the healthcare system and professionals as restricting many protocols that could have potentially become productive (HCP09-11 and 14-16). One pulmonologist gave the following comment on this:

Outside of Albert Luthuli, they [other facilities] do not have access to any of our electronic records, so we try to make a letter of the discharge summary as detailed as possible because outside of that letter, there is no other information that the receiving doctor will have. (HCP14)

In combination with the need for more streamlined processes, lack of interoperability sometimes impacts the continuity of patients’ care. One of the nurse practitioners maintained that if one chain breaks, it disrupts the entire process of patient care, which might work against the patient in terms of delaying the start of treatment and supportive care (HCP25).

Inefficiencies in written communication disrupting continuity of care

Continuity of care in a coordinated manner, in spite of all the complexities of the healthcare system and the different HCPs in different care settings, is ideal. However, this can barely be achieved without patient-centred care, whereby knowledge and information sharing transcend disciplinary and organisational boundaries. The exchange of information enables operating partners to understand the needs of patients and organise the correct response, increase timely response, and undertake appropriate coordination among themselves. Yet, issues mentioned by HCPs were instabilities in the continuity of care, specifically the transition from the community to the hospital and back to the community. The phenomenon described by continuity of care has been given various names in the literature, such as fragmentation of care.

Inconsistent communication as patients move through the system

There was a convergence of views among HCPs in that unreliable, delayed, and incomplete communication amongst the healthcare team were key barriers that inhibited the delivery of coordinated patient care (HCP01-26). Although participants identified collaboration of the healthcare team between and across specialties as foundational in the planning and implementation of coordinated care plans, they all felt communication between them was lacking, especially during care transitions (HCP01-26). Specialists do not consistently receive clear reasons for the referral, and primary care HCPs do not often receive information about what happened in a referral visit (HCP12, 20, 21, 24, and 25). Patients get down-referred to primary care for continued management without pertinent patient updates, as HCPs at the primary care would have lost touch with their patients while receiving treatment at a higher care level. Therefore, they advocated for more streamlined processes and direct communication from oncologists about managing patients’ cancer-related primary care needs, as delays in information risked patient care (HCP12, 20, 21, 24, and 25):

We [primary care] usually do not know why such a long delay exists. Maybe if we had a person referring the patient, informing us, please manage this patient because maybe they have got a long list of patients waiting for treatment or, you know, something like that. So, we have never been curious to say let’s find out why they are sending them back to us; we have never done that. Remember there was a time when it was reported on the news that only one machine works in our province [KZN]? We only learned that time. We did not know; maybe if it were well communicated, we would have known that nothing can be done because only one machine is used. (HCP12)

Physical distance did, to some extent, also facilitate or impede communication, although telephone and clinical notes should mitigate the impact of distance on patient care (HCP03, 07, 11, 15, 19, and 22). Yet, in most cases, mitigation was impossible as HCPs did not know who to contact in the healthcare team to get the required information (HCP05, 09, 21, and 24), as asserted by a social worker:

When a patient comes to us from other hospitals, they generally come with very poor referral letters with insufficient information about the patient’s comorbidities or their mobility history. And most of the time, we start from scratch when the patient comes to us even though they have a referral letter, which is a bit of a challenge. (HCP10)

Inadequate patient follow-up

In this study, systematic follow-up to ensure patients completed their appointments was not observed. None of the health facilities had done much to standardise processes for tracking and following up on cancer care provided to their patients. Most participants, especially from the primary level, suggested that opportunities to gather and talk with colleagues with whom they share the care of many patients should regularly be scheduled (HCP02, 06, 09, 21, 23, and 24). A radiotherapist and a medical officer gave the following comment on this:

…the computer is only for entering the information of what we have done, so there is no one responsible for whether the care was received or not. (HCP17)

Furthermore, it was explained that patients living with cancer were often seen by different doctors each time they were attended to due to limited resources (HCP12,13, 15, 16, 23, and 24). This becomes a limitation in terms of adequate follow-up and continuity of care and is a barrier that was recognised as being important in achieving coordinated care:

… you would find that in the district hospitals, different doctors rotate. This time you see this one, and next time you will see another one, but basically, we are just hoping that the next one that will attend to them will be able to carry on with the instructions and record too. (HCP24)

Opportunities for enhanced care coordination

Generally, participants’ recommendations to improve continuity and coordination of cancer care between services centred around providing timely and complete patient information from the primary hospital to the treating hospital and vice versa (HCP01-26). Participants encouraged smoother transitions back to primary care, which should include psychosocial and palliative care services (HCP02, 05-10, 12, 21, 24, and 25). The potential value of psychosocial services in providing patients with otherwise lacking services was mentioned numerous times (HCP02, 03, 05, 06, 08-10, 17 and 21). As a result, psychosocial support integration along the entire cancer care continuum was recommended to ensure patients receive support from a HCP with the appropriate skill set (HCP02, 05-10, 12, 21, 24, and 25).

The patient is the only person expected to carry information between providers at every appointment. For many patients, the nuances of who they need to connect with, and how and what to do to complete their care plan are not always apparent, as is the case for HCPs. Thus, participants proposed a case manager position to ensure that the patient’s proper connections and services were provided (HCP02, 03, 07, 13, 14, 16, 18, 21, 23, and 24). HCPs identified that allocating a ‘key contact’ (case manager) person was essential throughout the cancer journey, as asserted by the participant below:

Well, I suppose with coordinated care, what I would think is that there is somebody always in a specific department who is in charge of facilitating everything and keeping track of exactly what’s entailed in managing the specific patients. So, in this case, it would be patients with suspected or confirmed malignancy because often, multiple departments are involved. Things can get lost within communication, and along the way, so with coordinated care, it’s an entity, whether a department or a person, who will monitor these patients and ensure that they see the correct disciplines in the correct form. (HCP14)

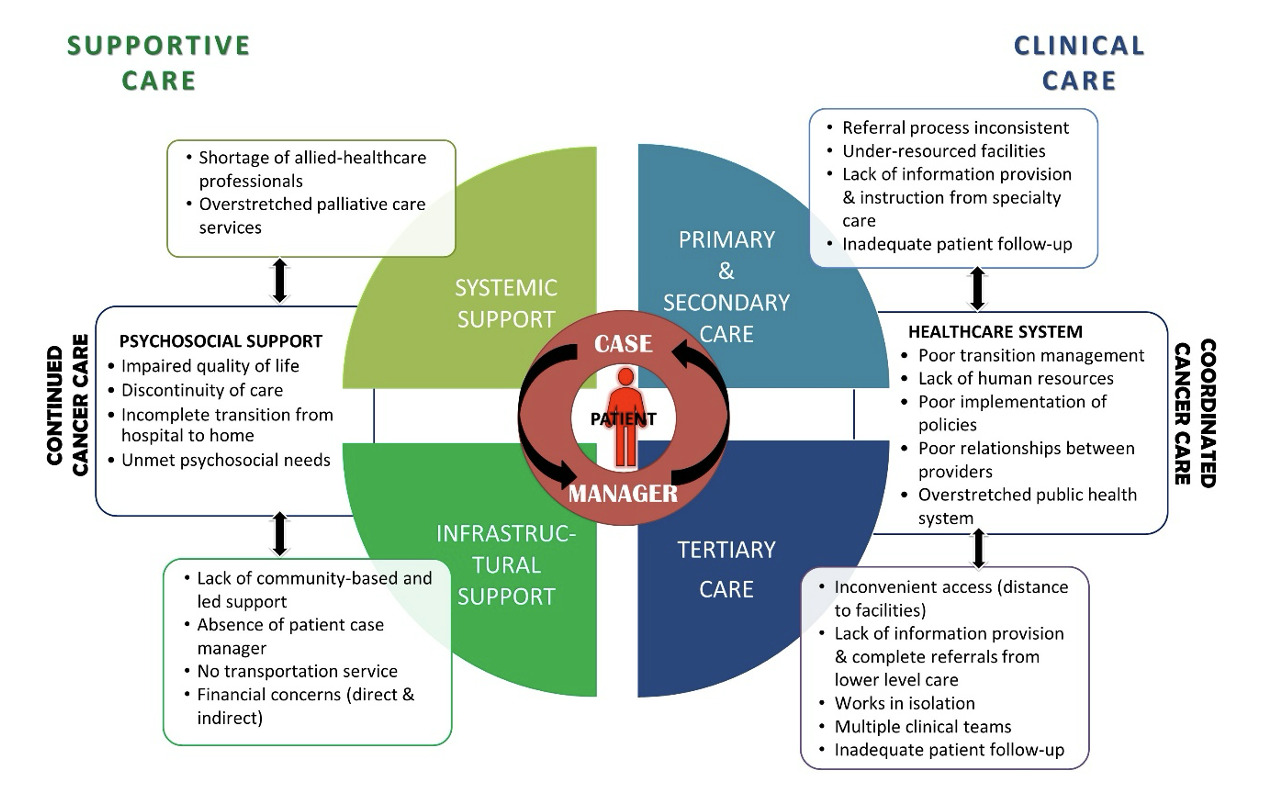

The findings presented in this paper can be summarised through the illustrative diagram in Figure 2. In addition, how patient care components could be linked have been added. Through bringing together several service functions, service coherence could increase and fragmentation decrease, thereby improving access, utilisation, and efficiency.

Discussion

This study’s principle findings were identifying the ten themes and sub-themes of cancer coordination-related challenges. Lack of coordination between care levels was found to be the key challenge in current care provision, and this is consistent with other studies.2,4,8,10,15,29,30 Service fragmentation, staff shortages, and referral problems emerged as overall public health system challenges, and these relate to systemic and structural challenges, resulting in widespread inefficiencies in healthcare delivery.2,4,8,10,29,30 Given health professionals’ views on how the fragmentation, lack of coordination, and weak referral chain of public health service provisioning influence the inefficiency of the health system, addressing the interaction among entities of this complex system is seen as the priority area which, in turn, is anticipated to decrease the chance of losing critical information as care responsibility transitions from one HCP to another.31,32

The contributing factors to the lack of care coordination were multifactorial and varied widely, with existing data pointing to multiple patient, provider, and health system factors.4,10,30,32 The most important barrier highlighted was the physical separation of the healthcare team members across different geographical locations, which reduced both the opportunity and frequency of communication. Furthermore, this barrier compromised the accuracy of patient information shared, which inadvertently weakened the care continuum. The limited interactive arrangement of systems also inhibited consultation and knowledge sharing among HCPs. This finding is consistent with a study in 2020 by Malakoane and colleagues, which posited ineffective information exchange as a critical factor contributing to HCPs’ inability to stay current with their patients’ care.32

Apart from an inadequate understanding of coordination, the lack of human resources and equipment was recognised as a limitation to coordinated cancer care. Congruent with other studies,4,9,30 a significant source of the problems is the understaffing of public hospitals, thereby placing high workloads on fewer staff. In the words of one participant (HCP16): “To say that the staff of public hospitals are overworked would be an understatement.” In this study, it was not established whether these factors led to a delay in entry to healthcare; however, other studies have shown that such factors can hinder timely healthcare.2,4,14,33 Nevertheless, participants recommended better communication, interoperability, and improved care transitions between providers and health systems.

The results of this study are consistent with conclusions reached in previous studies that care coordination is a complex concept intertwined with quality, delivery, and care organisation notions.33,34 Enabling the primary healthcare level to play a substantial role in care coordination may provide a plausible intervention to circumvent these complexities. Organisational structures and communication methods influence care coordination; hence, health system reform17,30 is worth considering, with the greatest efforts focused on healthcare system pathways. Notably, owing to the complexities of care coordination, extensive reorganisation and governmental improvements could result in new challenges30; thus a cancer care coordination model may need to be used as a pilot.

This paper presents a robust qualitative study of intersectoral care coordination for cancer patients based on individual in-depth interviews with primary to specialty public HCPs. The study’s strength is that all interviews were conducted by the same person (first author) who is experienced in qualitative research, thereby supporting the consistency of the methods.35 Its analysis is strengthened by its GT approach, where iterative data collection and analysis facilitated both the interpretation and development of probes.28 Although the study sought to involve a broad range of stakeholder views, insights from healthcare specialists at the secondary level may be under-represented. While the geographical spread of health facilities and care levels may limit the transferability of the findings, this was mitigated by the use of a maximum variation approach in recruiting participants from different organisations and specialties.

Recommendations

The knowledge gained through this study provides an opportunity to inform policy with future strategic and operational planning in so far as cancer care coordination is concerned. The study participants suggested improving cancer patients’ experiences by standardising care, adhering to guidelines, and using case managers.32 Government and healthcare organisations should incorporate principles of collaboration, care coordination, and insight into healthcare as a complex adaptive system in their induction programmes. As shown in other studies,36–40 the authors of this study believe that improved coordination has long-term benefits, including reduced costs and a more simplified and uniform approach to delivering cancer care across the system. Recent studies on cancer care coordination interventions have identified patient navigation, designated case managers, and collaborative care models as some of the proven common approaches.37–42 Care coordinators establish a remarkable continuity of care due to their availability outside regular hours and when urgent issues arise. Several areas within the lung cancer care continuum need to be addressed or improved in KZN. Some of the priorities identified in this study require financial resources, which were also listed as an important issue affecting lung cancer management in KZN.

Conclusion

The characteristics of a delivery system determine the timeliness, efficiency, and appropriateness of healthcare. As such, to strengthen the fragmented public healthcare system in KZN, there is particularly a need to improve integration and address human and financial deficiencies in this setting. This study’s important conclusion is not the challenges associated with documentation of communication and transitioning, but rather, that documentation of communication and transitioning still need to be adequately addressed. A fundamental change is required to shift the direction of the KZN public health system towards one that embraces comprehensive and coordinated care. National government needs to create a policy environment that enables citizens to have high-quality health systems. Recommendations from the HCPs generate an agenda to foster further research, practice, and policy innovations in cross-system care coordination. By pursuing this research agenda, it should be possible to develop novel approaches that successfully coordinate the increasingly complex nature of cancer care. The public health system needs to be patient-centred and responsive to patients’ needs at all levels, given that 80% of the population uses the public health system.17