Introduction

The global cancer burden is projected to increase from 19 million people diagnosed in 2020 to 28 million people by 2040.1 For South Africa (SA), between 2020 and 2040, the predicted increase in cancer incidence and mortality is 66% and 69%, respectively with significant socio-economic and health system consequences.1

Stage at diagnosis predicts cancer outcomes, with advanced stages being least responsive to curative treatment. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), most people are diagnosed with advanced stage cancer. Data from population-based registries show that almost two-thirds of women with cervical and breast cancer (65.8% and 64.9%, respectively) are diagnosed with advanced-stage disease.2,3 By comparison, fewer than a quarter of breast and cervical cancers (17.2 % and 21.4%, respectively) are diagnosed at an advanced stage in the United Kingdom (UK).4 Detecting cancer at an earlier stage improves outcomes and is an important goal in developing comprehensive cancer programmes.5 The World Health Organization recommends two early cancer detection approaches: screening of asymptomatic individuals, and early recognition and management of symptomatic individuals.5 This paper focuses on the latter.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have few cancer screening programmes, with most cancers diagnosed following symptomatic presentation. Even in high-income countries (HICs), most cancers (85-90%) are diagnosed following symptomatic presentation.6 Studies have shown that a shorter time between symptom recognition and first medical consultation is associated with better outcomes.7,8 Prompt help-seeking for possible cancer symptoms may facilitate earlier stage diagnosis and is influenced by community-level risk and symptom awareness, lay beliefs and access to care.9–11 The availability of locally validated measurement tools is key to measuring cancer awareness and developing and evaluating early diagnosis interventions.

In SA, people with possible cancer symptoms are first seen at primary healthcare (PHC) facilities with referral to secondary/tertiary facilities for diagnostic work-up. Minimising the time to diagnosis depends not only on public awareness of cancer symptoms but also on timely access to PHC providers, appropriate clinical assessment, and timely referral to diagnostic services.5

This paper maps the landscape of early recognition and management of people with potential cancer symptoms using results from the African Women Awareness of CANcer (AWACAN)12 project and other relevant local studies. It provides an overview of local community-level cancer symptom awareness, symptom appraisal, help-seeking behaviours and challenges faced by PHC providers in the management of potential cancer symptoms. This paper underscores the importance of prioritising early recognition and management of people with symptomatic cancer as part of comprehensive cancer control, providing insights for improving the journey to diagnosis.

Methods

This paper draws on the SA AWACAN project findings and a rapid narrative review of SA studies on journeys to cancer diagnosis.

SA findings from the AWACAN project

The AWACAN project, conducted in SA and Uganda from 2016 to 2020, focused on breast and cervical cancer. It included:

-

Developing and validating a tool to measure breast and cervical cancer awareness among women in SSA.13 The process included: item generation and refinement, and assessing test-retest reliability, construct validity and internal reliability, with translation of the tools into local languages.

-

Conducting a cross-sectional community-based survey in 2018.14 Data on symptom awareness, risk factors, lay beliefs, help-seeking behaviour, and barriers to care were collected using the AWACAN tool. Details of the methods are described elsewhere.14

-

Qualitative in-depth interviews (IDIs) with women with potential breast or cervical cancer symptoms identified during the cross-sectional survey.15 Interviews explored symptom recognition, appraisal and attribution, help-seeking behaviour, and barriers to accessing care, and were analysed thematically.

-

IDIs with PHC providers incorporating breast and cervical cancer vignettes explored provider symptom interpretation, reasoning, actions and challenges. Interviews were analysed thematically.16

In SA, the AWACAN studies were conducted in one rural site in the Eastern Cape Province (EC) and one urban site in the Western Cape Province (WC). The provinces were purposively selected as they represent different levels of wealth and health system infrastructure.

Narrative review of SA studies

A rapid narrative review, involving a scholarly summarisation with critical interpretation17 was undertaken. SA literature on community-level cancer symptom awareness, barriers to accessing care for cancer symptoms, the role of PHC providers in managing symptomatic patients, diagnostic challenges, and interventions to support symptom assessment, help-seeking and diagnosis, was summarised. Due to time and resource constraints, the review was limited to the PubMed database (Appendix 1). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 1.

Covidence was used for article screening, and data extraction. A narrative synthesis approach was used to analyse relevant findings.

Findings

In SA, the AWACAN project recruited 873 participants (428 EC, 445 WC) for the cross-sectional survey. Thirty-one women with symptoms were invited to participate in the IDIs of which 18 were interviewed (10 urban, 8 rural, median age 34.5 years). In total 24 PHC providers (12 urban, 12 rural; median age 43 years) were interviewed.

The narrative review search yielded 167 studies, with one duplicate removed. The PRISMA diagram (Appendix 2) summarises the screening process, with 30 studies included in the final review. Included articles addressed the following cancers: breast only (9), breast and cervical (6), cervical only (2), lung (6), prostate (3), lymphoma (2), and general (2).

Findings from the AWACAN study and the narrative synthesis review are presented below.

Tools to measure cancer awareness

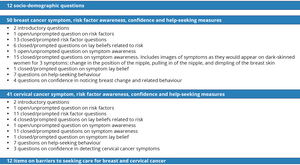

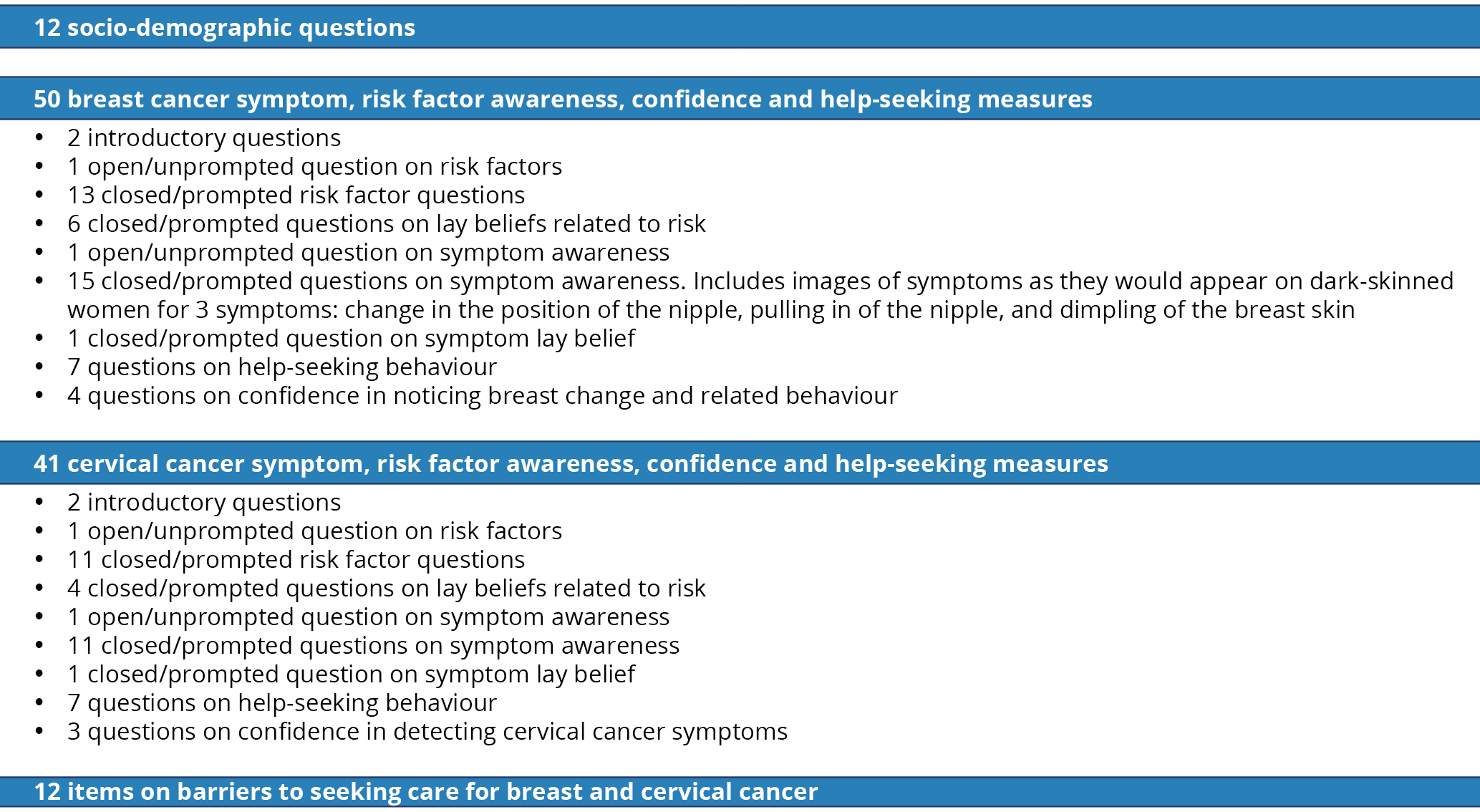

The AWACAN breast and cervical cancer tool demonstrated content, face, construct and internal validity, and test-retest reliability.13 The tool has 115 items (Figure 1) and is available online in English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa.12

The narrative review identified tools, other than the AWACAN tool, used to measure cancer awareness (Table 2).18–26 Three studies used the Cancer Research UK Cancer Awareness Measures tools (lung, breast and cervical cancer), with limited local validation.18,20,26 Another tool had some validation for use in the SA setting.21 Four studies used questionnaires, with few details provided on item development or validation.19,22–24

Community-level cancer awareness and lay beliefs

In the AWACAN survey, 85.7% of participants had heard of breast cancer (79.9 % rural, 91.2% urban) and 81.1% of cervical cancer (79.9 % rural, 82.2% urban).14 Recognition (prompted questions) of risk factors and symptoms was higher than recall (unprompted questions) for both cancers and at both sites. Recognition of breast and cervical cancer risk factors and symptoms by site is shown in Figure 2. Overall, the most recognised breast cancer risk factors were family and history of breast cancer, 66.4% and 63%, respectively.14 Modifiable risk factors, e.g., lack of physical activity, were poorly recognised. Overall, approximately a quarter of women were unaware that Human papillomavirus and not being screened were risk factors for cervical cancer, and 41.5% did not identify HIV as a risk factor.14 For breast cancer, a lump was the most recognised symptom (94.6%), while armpit symptoms were least recognised (78.0% armpit lump and 70.9% armpit pain). Abnormal vaginal bleeding and discharge were commonly recognised symptoms of cervical cancer (Figure 2d). Urban compared to rural women had significantly higher symptom (p<0.001) and risk factor (p<0.001) awareness for both cancers.14

The AWACAN survey found several lay beliefs: 89.8% viewed vaginal substance insertion as a cervical cancer risk, 75.0% believed wearing tight undergarments, and 92.0% thought putting money in a bra were breast cancer risks.14 The IDIs with symptomatic women also highlighted these lay beliefs, as illustrated below.

It is caused by putting money on the breast, putting a cell phone on the breast and always having something attached to your skin, that causes cancer. When you are going to put something on your breast, you must wrap it with a cloth… Yes, like you can put it in a handkerchief, don’t put something that will be in direct contact with your breast, or to your skin. That mark left by the money will cause cancer. [P015 age 39, urban, breast lump].15

The narrative review identified eight studies on community-level cancer awareness and beliefs (Table 3). Scholarship on breast, cervical, lung and prostate cancer demonstrates that community awareness of symptoms and risks is limited.14,19,24,27–34 Findings across studies showed that the most commonly recognised breast cancer symptom was a breast lump, with armpit symptoms less commonly recognised.22,26,29,34 Lung cancer symptoms, other than coughing blood, were poorly recognised, as were risk factors other than smoking.18 This is supported by findings from studies with key stakeholders, including oncology experts, who identified low community awareness as an important issue.31,32

Reported lay beliefs included cancer being a “white person’s” disease, resulting from witchcraft or curses, insertion of money in a bra, using soaps, and being contagious.28,29,32,35

Symptom appraisal, attribution and triggers to seeking care

In the AWACAN study, breast symptoms were often initially attributed to daily activities such as manual labour, wearing a tight bra, and placing money in one’s bra.15 Symptoms were monitored, and when persistent or painful, women sought help at healthcare facilities. For some, interpreting symptoms as possibly being due to cancer was informed by messaging from radio, social media and clinic staff, as illustrated below.

I was shocked [on finding a breast lump]. The reason was they are always talking about breast cancer, they say you first get a lump. And I also listen to the radio … and they [radio] say you must be shocked when you see a lump in your breast, so I was also shocked by that because I don’t want breast cancer. [P015 age 39, urban, breast lump].15

Cervical symptoms were attributed to possible cervical cancer, sexually transmitted infections, and the use of long-acting hormonal contraception.15

Most women discussed their symptoms within social networks, seeking opinions on the possible cause and guidance on further action.15 Some women with intimate symptoms were guarded in discussing symptoms for fear of stigma and gossiping. Triggers to seeking care included fear of cancer (see quote below), encouragement from family and friends, media and clinic health messaging, and interference of cervical symptoms with daily lives and sexual relationships.15

I was afraid. I wanted to get help as soon as possible. I have seen older women, especially in our village; there are so many older who have gone [passed away] because of cancer, …older women who would just bleed … then end up passing away, and then they find out that she had cancer… [P012, age 36, rural persistent lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge].

The narrative review findings on symptom appraisal, attribution and triggers to seeking care are summarised in Table 4. Scholarship demonstrates that many people do not appraise their symptoms as urgent and so are unaware of the urgency for care.26,28,32,34–37 In a study with patients with prostate cancer, Kim et al.38 noted that some attributed symptoms, such as erectile dysfunction, to ageing. Similarly, patients with breast cancer attributed symptoms such as loss of appetite and weight to ageing.34

Trupe et al.22 noted that, while participants had moderate levels of breast cancer knowledge, increased knowledge levels did not predict healthcare-seeking. Few participants had ever received a clinical breast examination (24.8%) or conducted a self-breast examination (33.3%).

For some patients with cancer symptoms, the absence of pain caused delays in accessing care as symptoms were appraised as minor.22,34 Worsening pain or other symptoms often prompted healthcare-seeking.14,26,36 Joffe et al.21 noted that women who took more than three months from breast symptom recognition to seeking care were more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage. There was diverging evidence on the role of traditional healers, with some studies noting that rural communities seek support from their traditional healers before seeking care for symptoms, and others noting that traditional healers are rarely consulted.27,32,34 Increased cancer awareness through social media, television and radio campaigns triggered health-seeking behaviour, as did supportive partners.29,34,36

Barriers to accessing care for cancer symptoms

The AWACAN cross-sectional study reported on anticipated personal, emotional, health service and practical barriers.25 Among urban participants, the most common anticipated barrier to seeking care was long health facility waiting times (18.7%); while among rural participants, it was not having money for transport or clinic costs (18.7%). Both barriers were mentioned in the qualitative IDIs, as were past negative experiences of language barriers, poor communication, and staff judgmental attitudes (as illustrated below), competing priorities, home commitments, and difficult unsafe travel to clinics.15

The doctor doesn’t ask you, he takes your folder, reads what’s inside, reads what’s written in there and then signs off your ARVs and after that he would just ask ‘Any problem?’ And then you say ‘No I have this, and this problem.’ You know sometimes English is not our mother tongue, so we become confused, you are sometimes unable to find the English word for something, you see. The doctor is then unable to understand what you are saying. And when the nurse comes in and just laughs at you… [P 001 age 36, urban, smelly vaginal discharge, abnormal vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain].

The narrative review identified several barriers to accessing care, notably fear of diagnosis and treatments, stigma, uncertainty about how to seek healthcare, distance to health facilities, long wait-times in clinics, cost of treatments, lack of transport funds, being turned away from clinics because of late arrival, competing personal responsibilities, bureaucracy at health facilities, lack of care coordination and referral across different healthcare levels.14,21,22,29,31,32,35,36,39

Experiences of PHC providers in managing patients with possible cancer symptoms

In the AWACAN study PHC providers demonstrated comprehensive clinical assessment for patients with breast and cervical symptoms.16 Cancer was considered as a possible diagnosis, as were infectious causes such as HIV and sexually transmitted infections and sexual assault (for cervical symptoms). Challenges experienced related to inadequate booking, referral and feedback systems. The need for provider and patient education to improve timely diagnosis of breast and cervical cancer was identified. Most PHC providers were unaware of breast or cervical cancer policy guidelines.16

The narrative review highlighted issues of symptom overlap and resulting delays. For example, lymphoma and lung cancer symptoms being misclassified as TB and women noting their breast symptoms had been treated with pain medication or antibiotics suggesting symptom misclassification.28,30,32,36,40 In contrast to the AWACAN findings, Tshabalala et al.28 reported that healthcare providers and managers were unsure about how to identify symptoms of cancer. Similar to AWACAN, there was an overarching sentiment that PHC providers required more support with early diagnosis and referral.30,32,39

A few studies highlighted the lack of communication between PHC providers and secondary or tertiary care providers. A qualitative study exploring cancer challenges noted that the trajectory of care in SA is saturated with service barriers, backlogs and language barriers.37 This was confirmed by an interventional study in KwaZulu-Natal.18

Interventions to support timely diagnosis

Based on the AWACAN findings, the project has extended to the AWACAN-ED (African aWAreness of CANcer and Early Diagnosis)12 programme, which aims to develop and evaluate interventions to support early breast, cervical and colorectal cancer diagnosis in Southern Africa.

The narrative review identified two intervention studies. A quasi-experimental study examined the impact of a community intervention on lung cancer awareness.18 One month after implementation, lung cancer symptom and risk factor awareness significantly increased. The lack of details on the intervention and the short time between the pre- and post-intervention assessments limit conclusions. Another study assessed the feasibility of a short training intervention supporting rural PHC providers to use ultrasound for breast assessments.41 Pre-post results indicated programme acceptance and increased competency, suggesting that ultrasound may be a viable option for breast symptom assessment.

Discussion

Timely diagnosis and management of people with possible cancer symptoms is an important distinct approach to improving early cancer diagnosis. This paper has summarised relevant SA studies. Although several studies measured cancer awareness and lay beliefs,14,18–26 comparison across studies is hampered as most did not use validated tools or provided limited information on the tool/questionnaire development. The AWACAN tool adds a much needed validated tool in this setting and is now available for future use to measure the impact of awareness initiatives. It can be adapted for other cancers. A wealth of literature on psychometric principles and validation is available and must be used to guide cancer awareness measurement.42 Where tools have been validated in other countries, local validation, beyond translation, is important to account for contextual differences.

Community-level cancer symptom and risk awareness is an important first step on the journey to cancer care. The few SA studies that measured community knowledge reported concerningly low awareness across different cancers. Participants mentioned receiving information from the media, indicating an opportunity to address awareness with well-designed media campaigns. Studies elsewhere have shown positive results with carefully designed community awareness programmes.9,11,43 The AWACAN study showed significant urban/rural differences in cancer awareness, which must be taken into account in developing targeted interventions. Awareness programmes also need to address lay beliefs as these impact symptom interpretation and timely healthcare seeking.

Social networks are important for symptom appraisal and health-seeking behaviour. Efforts to address ongoing stigma and cultural barriers are urgently needed and will require multi-stakeholder involvement, including engagement with local leaders and communities.

In SA, PHC providers are the first point-of-contact in the public sector. PHC providers manage a range of patients and undifferentiated problems, making the task of triaging and managing those with possible cancer challenging. PHC providers identified training and support needs. Elsewhere, tools have been developed to assist PHC providers.44,45 SA tools that support PHC providers and consider the local disease context and health system technology infrastructure are needed. Adapting existing SA PHC provider tools such as Vula Mobile could be explored.46

This study identified several barriers to accessing timely care within the healthcare system (e.g., cumbersome referral), and outside it (e.g., safety and distance). For many people, accessing care is a complicated process of negotiating intersecting barriers. Barriers should address the use of a whole-of-society approach, as benefits extend beyond cancer care.

Very few interventions to improve timely diagnosis for people with symptoms have been developed and evaluated in SA. This is an urgent need, given the increasing cancer burden and advanced-stage presentation.

Recommendations

-

Efforts to support early diagnosis of people with possible cancer symptoms receive attention, alongside screening for asymptomatic people.

-

Implement multi-sectoral initiatives to overcome early diagnosis barriers at individual, community, and health systems levels.

-

Researchers commit to developing locally validated cancer awareness measurement tools to guide and evaluate early diagnosis interventions.

-

Prioritise efforts to support PHC providers in managing people with possible cancer symptoms.

-

Adapt referral systems to prioritise patients suspected of having cancer.

-

Engage diverse stakeholders (e.g., policymakers, community leaders, patient advocates) in designing and implementing strategies for early diagnosis, to ensure feasibility, acceptability, and responsiveness to local needs.

Conclusion

Ensuring earlier diagnosis of people with possible cancer symptoms is achievable with accurate cancer awareness measurement, a better-informed population, a strengthened health system, and multi-sectoral commitment. Overcoming barriers and leveraging enablers in the early diagnosis of symptomatic cancer holds potential for improved outcomes.