Introduction

Surgery plays a pivotal and irreplaceable role in the comprehensive management of 80% of patients with cancer.1 Surgical intervention may have a curative or palliative intent. The risks of complications are inherent in surgical procedures and can lead to delayed recovery, prolonged hospital stay, and increased healthcare costs.2 Actively reducing complications can have significant and far-reaching benefits. By prioritising and embedding efforts to minimise complications, healthcare providers not only mitigate the physical and emotional burdens on patients but also contribute to enhanced patient safety, reduced length of stay (LOS), earlier return to intended oncology treatment (RIOT), and a more streamlined and efficient healthcare system.3,4 Investing in strategies to improve perioperative care is thus crucial.

In this paper, insights from implementing an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programme for colorectal cancer patients in the public and private sector in Cape Town are presented.

Context

In South Africa (SA), perioperative cancer care is fragmented, seldom patient-centred or evidence-based with limited availability of well-functioning multidisciplinary teams and monitoring and evaluation tools. In addition, there is a lack of robust data on LOS, complications, mortality, quality of life (QoL), and RIOT after cancer surgery.5,6 The Global Surgery Collaborative study, a multicentre, prospective cohort study conducted in 82 countries and among 15 958 patients, provides a global perspective on perioperative outcomes in high and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).7 In that study, the proportion of patients who died after a major complication was highest in LMICs, with postoperative death after complications partly explained by patient (60%) and by hospital or country (40%) factors. Failure to identify and intervene in patients who were deteriorating after a complication (failure to rescue), was an important contributory factor to the higher mortality. The absence of consistent postoperative care facilities was associated with 7-10 times more deaths per 100 major complications in LMICs. Cancer stage alone explained little of the early variation in mortality or postoperative complications.

Improving perioperative care is complex. Every surgical procedure requires careful planning prior to commencement and a well-functioning perioperative multidisciplinary team (patient, nurses, anaesthetists, surgeons, pharmacists, hospital managers, policy makers). The teams need to implement 20-25 key perioperative care elements to achieve improved patient outcomes. Key micro (e.g., essential drugs, oxygen, sterilised equipment) and macro resources (e.g., reliable water, electricity supply) need to be available. Improving care also requires adequate change-management and ongoing quality assurance.

The ERAS programme is an innovative service delivery platform for improved perioperative care that leverages the key principles of the WHO quality improvement framework.3,8 Institutions that have implemented the ERAS programme in different countries across the globe have reported a reduction in complication rates (20-25%), hospital stay (20-25%), in-hospital costs (10-25%), and nursing workload.9–11 A recent study from Sweden reported that the 5-year cancer-specific mortality rate decreased by 42% when compliance with ERAS guidelines was above 70%.12 Fewer studies have been conducted in LMICs but studies that have been conducted in these settings have achieved comparable results.13,14

The ERAS programme

The ERAS programme is based on three pillars:

-

standardised evidence-based guidelines,

-

an implementation programme, and

-

a monitoring and evaluation tool.

Pillar 1: standardised evidence-based guidelines

The ERAS management guidelines address 20-25 elements of care in the pre-admission and pre-, intra- and postoperative period that are applicable to most cancer operations (Table1). Addressing these elements of care reduces the perioperative pathophysiological catabolic stress response and immunosuppression and allows the patient to eat, drink and mobilise sooner, i.e., faster recovery.

Pillar 2: implementation programme

The ERAS implementation programme focuses on establishing a well-functioning multidisciplinary team (MDT) able to implement the evidence-based guidelines. The 10-12-month implementation programme employs change management principles and features a series of MDT workshops and periods of active implementation. The MDT members include: the patient and their families, surgeon, anaesthetist, nurse care coordinator (NCC), nursing and theatre teams, physiotherapist, dietician, physician, data capturer, hospital management, and administrators. All members have a defined, unique and critical role in implementing the elements of perioperative care. A key member of the team is the ERAS NCC who supports the patient from the time of diagnosis to 30-days follow-up post discharge, manages the preoperative counselling, risk assessment and discharge planning, oversees intra- and postoperative care, data capture, and provides essential training to the MDT members.

Pillar 3: monitoring and evaluation tool

The ERAS monitoring and evaluation system, the ERAS interactive audit system (EIAS), allows the teams to continuously monitor adherence to the guidelines, measure outcomes and effect change. This is based on the Deming Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle.15 The ERAS database is web-based and available in real time. It is designed to allow centres to conduct relevant research and to benchmark results against other centres.

Methods

The ERAS programme was implemented in a public and three private sector hospitals in Cape Town, South Africa, for patients undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery (September 2016 to June 2023, and April 2015 to April 2020, respectively). The public sector arm commenced later due to delays in recruitment of the ERAS nurse coordinator.

A dedicated perioperative ERAS MDT was established in each sector, and each worked independently.

The private sector MDT included:

-

2 NCCs

-

9 surgeons

-

5 anaesthetists

-

3 physiotherapy teams

-

2 dieticians

-

1 stomatherapy team

The public sector MDT included:

-

1 NCC

-

2 senior colorectal surgeons

-

many surgical registrars in rotation annually

-

1 lead anaesthetist

-

1 physiotherapy team

-

1 dietician

-

1 stomatherapy team

-

2 hospital management personnel (CEO, surgical services manager)

The MDTs reviewed and implemented the ERAS evidence-based colorectal guidelines without any changes to the pre-admission and pre- and intraoperative period. For the postoperative period, the following items were added to the ERAS guidelines for the NCC: bi-daily ward visits, and telephone patient contact for a minimum of three days post discharge with a checklist questionnaire. Additionally, in the public sector hospital, every patient received a 24-hour emergency contact number, with a ‘call-me’ option. The lead surgeon and ERAS nurse coordinators met weekly and the entire MDT quarterly as part of the PDSA process.

Participant recruitment and measurements

Verbal consent to collect clinical data was obtained from all patients 18 years and older undergoing elective colorectal and/or small bowel surgery. Patients were enrolled consecutively. Although patients with both benign and malignant conditions were enrolled in the ERAS programme, for this analysis only patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer were included. All data were anonymised and entered in the database by the NCC. The following variables were measured: age, sex, pre-admission clinical details, pre-, intra- and postoperative clinical details, and compliance with the ERAS guidelines. See Appendix 1 for details on perioperative variables. Cancer stage was recorded using the stage and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, also called the Tumour, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging system. The primary outcome measures were LOS, complications, and compliance with the guidelines. The LOS was defined as the duration (nights) spent in hospital from the date of admission to discharge. Any patient requiring readmission and/or repeat surgery within 30 days after the index operation was recorded. All complications occurring within 30 days of the procedure were recorded. The complication rate was calculated as the total number of complications divided by the total number of patients undergoing surgery. The Clavien–Dindo grade classification was used to classify complication events, as defined in the ERAS guidelines.4 The calculation of compliance (yes/no) with the ERAS guidelines was generated by the EIAS software. Any missing compliance data were recorded as non-compliant. Overall compliance reflects the average of the pre-admission, pre-, intra- and postoperative compliance. The impact of the degree of compliance on LOS and complications was assessed. The learnings from the weekly and quarterly meetings and the implementation workshops were recorded.

Data analysis was conducted using STATA v.16.16 Public and private sector data were analysed separately and not compared due to potential confounders such as the timeframe and other unmeasured differences between the two sectors. For continuous normally distributed variables, means and standard deviations are reported, while medians and interquartile range are used for distributions that were significantly skewed (Shapiro-Wilks test, p<0.05). For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages are reported. Within each data set, associations between LOS, any complication at 30 days, and overall compliance were assessed using linear regression of log transformed LOS, and logistic regression, respectively.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.17 Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town, South Africa (HREC 980/2023).

Results

A total of 556 and 514 patients were enrolled from the public and private sectors, respectively. In total, 368 public and 325 private sector patients had elective colorectal cancer surgery. Tables 2 and 3 summarise key demographic and clinical data for both sectors. Of note, in the public sector there was a trend of high American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) scores, a greater number of patients requiring neoadjuvant therapy, and a prolonged use of opioids postoperatively.

The overall median LOS was 6 (IQR 4-9) and 4 (IQR 3-7) days in the public and private sectors, respectively, with a readmission rate of 12% in both sectors. The complication rate per Clavien-Dindo grade for complications and the common complications are shown in Table 4.

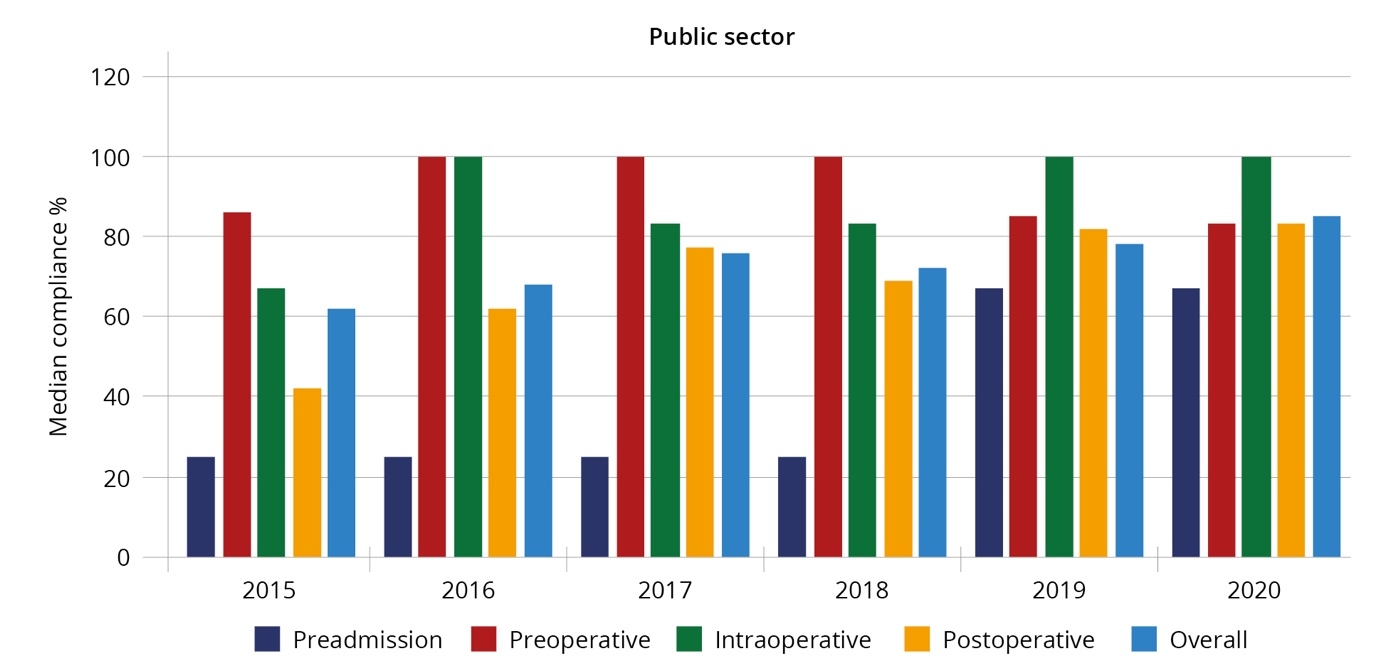

Compliance is reflected in Table 5. Over the study duration, pre-admission and postoperative compliance was lower than preoperative and intraoperative measures in both sectors.

The median pre-admission, pre-, intra-, and postoperative, and overall compliance with the ERAS guidelines in the public and private sectors per year are reflected in Figures 1a and 1b.

In both sectors, as overall compliance increased, LOS significantly decreased (Exp coefficient 0.98, 95% CI= 0.97-0.98; p<0.001[public]) and (Exp coefficient 0.98, 95% CI=0.98-0.99; p<0.001[private]). In both sectors, as compliance increased the odds of complications significantly decreased (OR (unadjusted)=0.96, 95% CI= 0.93-0.98; p=0.001[public]) and (OR (unadjusted)=0.97, 95% CI= 0.95-0.99; p=0.001[private]).

The key learnings of the weekly and quarterly meetings and the implementation workshops are summarised below. The NCCs’ notes identified lack of transport as a barrier to early discharge in the public sector. Implementing post discharge 24-hour availability for emergencies, and the daily telephone calls, helped to identify possible complications and reassured patients. Both sectors experienced a shortage of resources such as chairs and private spaces. Patients, surgeons, and nursing staff often challenged the early mobilisation and feeding guidelines as this was contrary to their previous knowledge and practice, and they feared medico-legal implications.

Discussion

Both LOS and complication rates are fundamental, albeit indirect, measures of the quality of care provided. The limited available data reflects a median LOS of 9 (IQR 9-16),18 and 11 days (IQR 7-15)19 for colorectal cancer surgery in SA. Both these studies imply that 25% of patients have a LOS of 15 or more days. Encouragingly, in this study, the overall median LOS in the public sector (6 days, IQR 4-9) and private sector (4 days, IQR 3-7) are more favourable than others reported in SA and comparable to international benchmarks. The readmission rate of 12% in both sectors is in keeping with results of established ERAS centres. There are several benefits associated with a reduced LOS for the patient and healthcare system. For the patient, streamlined service delivery and shortened recovery offer the possibility of fewer complications, improved QoL, and earlier RIOT. The healthcare system benefits include increased bed availability, improved efficiency, and cost reduction.3

Whilst there are numerous benefits to reducing LOS, this must be achieved without compromising the quality and safety of care. Establishing and maintaining appropriate support systems, such as effective preoperative discharge planning, adequate outpatient care, and follow-up need to be in place to ensure that patients receive the necessary care after hospital discharge. An important public sector barrier to early discharge was lack of transportation. Addressing this requires intersectoral collaboration.

The overall median complication rate compared favourably with international benchmarks from established ERAS centres worldwide.3 Scaling up ERAS has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes, facilitate resource allocation, and improve the health service delivery platform in SA. The common complications of postoperative ileus, surgical site infection, pulmonary atelectasis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections were less frequent than those reported in the literature for patients undergoing traditional care. This is probably a reflection on the benefits of optimal perioperative care.

Compliance measures adherence to the guidelines and is an indirect measure of the effectiveness of the MDT. Established ERAS centres with compliance levels greater than 70% consistently report lower LOS and fewer complications, with a reduction in LOS and complications as compliance improves.20 In this study’s ERAS programme, the overall median compliance was 72% in the public and 79% in the private sector, with a significant impact on LOS and complication rates. Post-operative compliance, a key measure of patient recovery, improved in both sectors, but the public sector was not able to reach the target of 70%. Possible contributing factors include: the high use of opioids postoperatively, need for ongoing staff training, and shortage of resources (e.g., space and chairs). Achieving postoperative compliance (e.g., feeding and mobilisation) challenges many long-held belief systems by patients and healthcare professionals. Future ERAS programmes need to adequately address these.

Each healthcare professional involved holds a distinct and vital role in addressing the various elements of care, necessitating mutual understanding and collaborative efforts. Nursing staff play a pivotal role in supporting and facilitating the implementation of early feeding and mobilisation. Dieticians must ensure that nutritional requirements are established and consistently met. Surgeons, anaesthetists, physicians, and pharmacists collectively contribute to optimal pain and fluid management, while physiotherapists are essential in initiating patient mobilisation. Operationally, creating dedicated spaces for seating and mobilisation is essential. Successful and sustained implementation of these changes relies on the synergy, coordination and shared commitment of the entire healthcare team.

The NCC serves as the vital link connecting patients and the MDT across the entire spectrum of care and provides essential support and training. In SA, although the SA Nursing Council (SANC) has ring-fenced perioperative care as a nursing speciality, to date there is no dedicated teaching for nurses at under- or postgraduate level.

A limitation of the study was the lack of baseline data which would have enabled a pre- and post-ERAS comparative analysis. International data show cost savings of between 20–25% and a return on investment between 5–7: 1 within the first year.21,22 If similar savings can be achieved in SA, there is a possibility of optimising the use of current resources and improving patient outcomes. Costing studies that include the entire patient journey are required to achieve uptake at the scale of ERAS programmes in the SA setting. User experience, particularly that of the patient, has been generally positive from anecdotal reports, but needs to be fully assessed. This could be achieved through collection of patients’ reported outcome measures or using a qualitative approach incorporating patient interviews and the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) tool.

The results achieved in these pilot projects hinged on the following key factors: strong leadership, well-functioning MDTs, a dedicated implementation programme, and a robust quality improvement framework. Although these results were achieved in elective colorectal cancer surgery, the programme lends itself to, and is available for, the management of major cancers across all disciplines.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the following are recommend:

-

Tertiary and quaternary academic units in SA establish perioperative hubs to implement the ERAS programme or similar and establish centres of excellence in perioperative care.

-

Intersectoral collaboration to address the identified barriers.

-

Liaison between the MDT, oncologists and palliative care specialists in ongoing patient care.

-

Development of national policy and guidelines on perioperative best practice.

-

Training at under- and postgraduate level for all MDT disciplines on perioperative care.

-

Once established, the academic hubs should collaborate with secondary hospital clinical leads, hospital managers and policy-makers to develop tailored implementation programmes with monitoring and evaluation tools.

Conclusion

The ERAS programme, with its focus on improving perioperative care, has the potential to significantly and meaningfully improve outcomes for cancer patients requiring surgical interventions in South Africa.