Introduction

Globally, cancer is a major health and socio-economic concern.1 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to reduce premature mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cancer. The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs aims to reduce mortality due to NCDs, including cancer, by 25% by 2025.2

South Africa (SA) is faced with increasing incidence, significant morbidity among cancer survivors, and high mortality.3 In 2022, there were 111 321 new cases reported, and 64 547 deaths.4 Several factors contribute to the growing cancer burden in SA, including lifestyle changes, improved diagnosis and reporting, higher life expectancy of patients living with HIV, and an aging population.3 Research has identified several reasons for poor survival among cancer patients, including health systems issues.5,6 For example, delayed diagnosis and treatment is linked to the shortage of oncology specialists, the distances patients need to travel in order to access specialist services, poorly functioning referral systems, reduction in specialist posts in the public sector, and the unavailability of essential cancer medicines and radiation facilities, due to them being highly priced, out of stock, or discontinued. Thus, although access to effective cancer management is a complex issue involving every step from diagnosis to treatment, two key issues that should be addressed are (a) developing and implementing policies that prioritise cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment, and (b) providing referral pathways to comprehensive healthcare services, especially for those living in rural and underserved areas.

Addressing the complex challenges associated with cancer requires a co-ordinated effort, an all-of-government approach, involving healthcare providers, civil society and the community and the private sector.7 SA’s National Cancer Strategic Framework (NCSF) 2017-2022 encapsulates “government’s commitment to providing equitable and affordable access to cancer services and treatments”, but acknowledges that “treatment costs are often unacceptably high, making many standard-of-care treatments unaffordable for partially insured or uninsured patients.”7 Part of government’s commitment should be to ensure equitable access to all oncology medicines; an issue facing both the public and private sectors. While access to effective cancer treatment involves both affordable and less affordable medicines, the latter poses a globally important barrier to care.

Current pricing policies in South Africa

The focus of the South African Health Product Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) is predominantly on efficacy, quality and safety. The current medicines pricing interventions are administered by the National Department of Health (NDoH), advised by the Pricing Committee. In the SA private sector, a non-discriminatory ex-manufacturer price, the single exit price (SEP), is charged to all buyers, regardless of the volumes procured. The SEP includes a logistic fee component and value-added tax. The legislation also imposes a ban on volume discounts, rebates, or sampling. After the designation of a launch SEP, which is entirely at the discretion of the holder of the certificate of registration (HCR), the SEP is subject to a maximum annual SEP adjustment set by the Minister of Health, on the advice of the Pricing Committee.8 All SEPs for medicines marketed in the private sector are published on the NDoH website, to ensure visibility. Although described as transparent, the SEP does not disclose the components of the ex-manufacturer price, such as the actual cost of production.

Medicines selection in the private sector is complex and fragmented. Each of the 71 registered medical schemes may include different benefit options, although these are subject to the prescribed minimum benefits imposed in terms of the Medical Schemes Act of 1998.9

Medicines selection in the public sector follows an evidenced-based approach to develop Standard Treatment Guidelines (STGs), from which Essential Medicines Lists (EMLs) are extracted. Procurement is based on a national competitive tender process, limited to SAHPRA registered products. Although the STG/EML can be considered indicative, it does guide provincial procurement as the provinces participate in the transversal tenders.10 Cancer treatment is regarded as a tertiary/quaternary service, for which STGs are not developed, but items are included on the tertiary/quaternary EML and therefore procured on tender. However, where suppliers decline to tender, some essential medicines have to be procured on quotation by individual provinces.

While acknowledging the many health systems challenges to accessing cancer care, this project sought to understand the challenges with access to oncology medicines in SA and to identify viable solutions through engagements with the various stakeholders across the pharmaceutical value chain.

Methods

Medicines access issues previously identified by the Cancer Alliance were extracted and used to develop the case scenarios for dialogues with stakeholders.11–13 Dialogue is a well recognised tool for exploring different voices, and different experiences and as a space for clarifying issues and creating new understandings or solutions, and is based on grounded theory.14 It allows people to move beyond their entrenched positions once they view others’ input and experiences. The project sought to bring together stakeholders from various parts of the pharmaceutical supply value chain; each with their own voice and experiences.

Participants

Dialogue sessions, termed ‘Solution Labs’, were held with a small group of selected stakeholders (N=20) across the pharmaceutical value chain between June 2022 and September 2023. A representation of participants across the pharmaceutical value chain was identified from the authors’ networks. Participants included policymakers, medical scheme funders, pharmaceutical industry representatives, civil society, patient advocacy groups, academics, and international experts. The same representatives were invited to all the sessions, but not all participants were able to contribute to every session.

Dialogue sessions

A total of eight 90-minute sessions were conducted, focussed on solutions to the identified challenges being faced in access to cancer treatment.6,11–13 The process was designed to encourage proactive advocacy and solution-building and to work with existing resources to find solutions that were considered to be contextually relevant, sustainable, and suitable. The number of participants was deliberately limited, to allow constructive debate and input from all stakeholders along the value chain. Each session started with presentations from invited guests, to create a platform for debate, to challenge and refine viable solutions, and to ensure buy-in and feasibility. Local and international presenters were purposively identified from the authors’ networks. Representatives from the national and provincial Departments of Health were invited to participate, but were not present at any of the sessions.

Themes for discussion

The discussion topics were extracted from previous publications by the Cancer Alliance.11–13 The identified topics related to access to high priced oncology medicines were:

-

the use of section 21 authorisation and section 36 exclusions for enabling access to high-priced and ‘abandoned’ older medicines;

-

the use of evidence in medicines selection;

-

pricing policies that might promote equitable and affordable access;

-

value-based care for cancer and the role of alternative reimbursement models (ARMs);

-

pooled procurement opportunities; and

-

effective use of the legal system.

The same thematic categories were therefore used to analyse the solutions generated, using a deductive approach.

Ethical considerations

The Solution Labs formed part of a broader project examining barriers and facilitators to access for innovative medicines. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC/00005116/2022). Sessions were recorded and key challenges with viable solutions were identified from the discussions and extracted from the sessions, without identifying participants in the value chain to ensure participant confidentiality.

Findings

The sub-sections below provide a brief overview of the session topics, the subsequent discussion, and the key solutions that were proposed.

Section 21 and access to oncology medicines

Section 21 of the Medicines and Related Substances Act of 1965 (as amended)8 enables access to unregistered medicines, usually for the treatment of a particular patient. Specific permission is required from SAHPRA. In addition to individual patient applications, SAHPRA may also consider bulk applications (where medicines are needed on an urgent basis and are held by health facilities in anticipation of specific patient needs) and applications from the Affordable Medicines Directorate of the NDoH when facing medicines stockouts. More recently, section 21 has also been relied upon to enable rapid responses to public health emergencies, particularly for COVID-19 vaccines.15,16

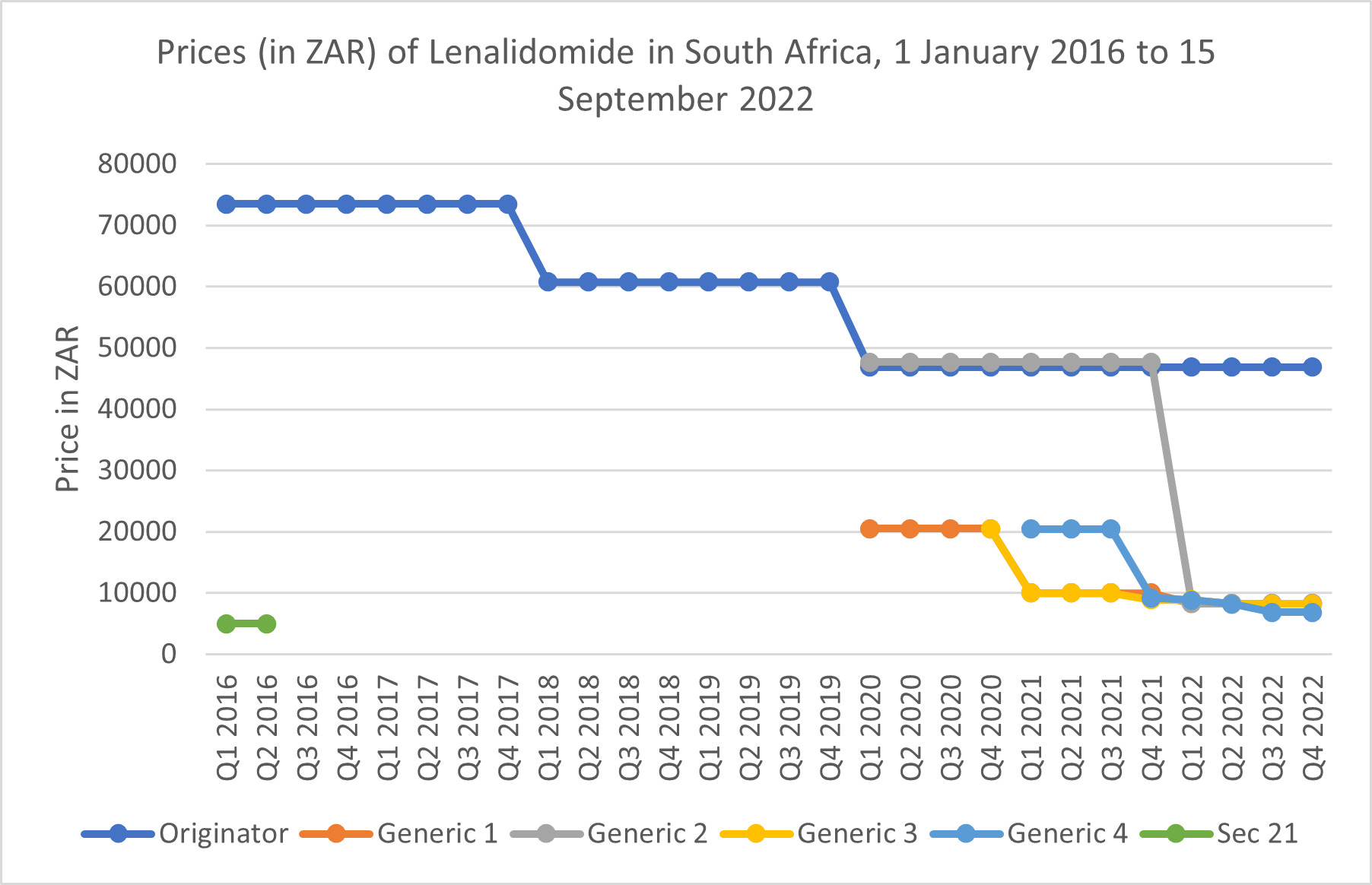

Two case studies based on real experiences of medicines that had not been formally registered and marketed in the country but were needed, were presented. The first looked at the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with an unregistered medicine (nivolumab), one at a public sector tertiary hospital and another in the private sector. Both patients were quoted vastly different prices for the same medicine by two different importing companies. The second case dealt with access to lenalidomide for the treatment of multiple myeloma in the private sector prior to the registration of this medicine by SAHPRA. Section 21 enabled access to generic lenalidomide before the originator product was registered by SAHPRA in 2016. The initial launch SEP for the registered originator product was far higher than the price previously charged for the section 21 generic product, but section 21 could no longer be used to enable access to the lower priced alternative once lenalidomide was commercially available. Generic lenalidomide products only became available after 2020, resulting in a marked reduction in the price of the innovator product. These experiences highlighted the non-transparency of pricing for products imported in terms of section 21. How those prices are set, and why they varied so much between companies and between opportunities for importation, were points of discussion.

Participants highlighted that price variation was due to a number of factors, including: where quality-assured medicine could be sourced, whether the quantities procured were for a single patient or a bulk order, and the distribution costs involved (such as air freight). Other participants also indicated that prices for unregistered medicines had to be negotiated between importers and suppliers outside of the control of South African regulators. Although a key issue remains the means to encourage registration of needed medicines in SA by innovator and generic companies, participants suggested that SAHPRA consider requiring applicants to obtain at least three quotes (where available) from possible suppliers, with lead times, so that patients can exercise some choice based on the urgency of their treatment. The participants also highlighted the need for enhanced transparency regarding section 21 decisions (such as a website detailing the approvals that have been issued), so that other prescribers and patients are able to access the details of previous approvals. This would address the current information asymmetry which places patients and their prescribers at a distinct disadvantage.

The second scenario looked at the difference between the launch price of lenalidomide compared to the previous price for generic products imported in terms of section 21 (see Figure 1). As can be seen, the launch SEP was far higher than the price for imported section 21 generics. Only after four generic products were registered did the SEPs approximate those paid previously for the imported product.

Participants highlighted that the process of determining an initial launch SEP is not transparent, as the ex-manufacturer price determination remains murky. At present, the NDoH has no influence on the determination of this price. Although section 15C of the Medicines and Related Substances Act of 1965 (as amended)8 enables parallel importation, this option has not been used by either the public or private sectors to access more affordable medicines. HCRs can apply for specific exemptions from the SEP mechanism for individual medicines. While, theoretically, this would enable the use of alternative pricing tools, such as negotiated volume discounts, some participants felt that it would not be a viable option for the large number of high-priced oncology medicines which might need exemptions.

South African prices are globally visible, as private sector SEPs are published on the NDoH web site, as are the prices awarded in transversal tenders for supply to the public sector. The pharmaceutical industry is concerned that SA prices are referenced by other countries in their own external reference pricing systems. Manufacturers are therefore reluctant to announce SEPs if those prices might be used to exert downward pressure on pricing in other markets. In typical application of market segmentation, manufacturers prefer to negotiate specific prices with medical schemes, accessible only to beneficiaries of those schemes. Some participants raised the challenges of the varying capacity of medical funders and their administrators to engage in such negotiations in SA if alternate pricing tools could be used. Potentially, this would result in inequitable access, not only for beneficiaries of smaller and less well-resourced schemes, but also for those who cannot access free care in the public sector, and also cannot afford private insurance, so they must pay out-of-pocket (the SEP) for medicines. Overall, this debate revolved around the attempt to parse the meaning of ‘transparency’ and ‘visibility,’ where HCRs claim not to oppose the former, but decry the latter.

Using health technology assessment in medicines selection

Although elements of health technology assessment (HTA) are used by both the National Essential Medicines List Committee (NEMLC) and by medical schemes,17 both sectors face difficulties with providing access to oncology medicines. An additional challenge facing the application of HTA is the paucity of evidence for the benefits of some newly developed and high-priced oncology medicines which rely on accelerated approval procedures.18

Medical schemes apply HTA techniques in reviewing the evidence base for therapies and defining a clinical pathway and target patient populations that can access these therapies. Within these HTA techniques, cost-effectiveness and budget impact are considered. However, they are constrained by the SEP policy, in that they are unable to access differential pricing or alternate reimbursement models, including those that propose to link payment to clinical performance. The public sector is able, by contrast, to use its buying power to exert downward pressure on prices.

Linking prices and reimbursement to clinical outcomes is challenging, according to participants, as it requires close tracking of patient experience and outcomes. Risk-sharing agreements demand that clear performance targets are set in advance. Such real-world evidence of effectiveness should be shared with regulators and policymakers, aiding in evidence-based decision-making, rather than being kept within the confines of single medical schemes. The objective of such risk-sharing arrangements is to reduce prices and/or to remove co-payments entirely, thereby reducing financial burdens on patients.

Overall, the participants proposed that a fundamental review of the entire pricing policy structure applied in both the public and private sectors was needed. It is particularly important to note that there is still considerable uncertainty about how medicine prices will be determined under National Health Insurance.19

Legal means to advance access to oncology medicines

A further dialogue session focussed on the legal tools, experiences, and opportunities that can be exploited to ensure access to affordable medicines. To set the scene, the Pharmaceutical Accountability Forum in the Netherlands was described.20 This is a non-government organisation focused on access to medicines, especially high-priced medicines. Using the human rights guidelines for pharmaceutical manufacturers initially outlined by Paul Hunt in 2008,21 the Pharmaceutical Accountability Forum has developed a 19-criterion scorecard which ranks pharmaceutical manufacturers in terms of access to medicines. Price transparency is key to such efforts. The World Health Assembly Resolution 72.8, adopted in 2019, calls on countries to “take steps to publicly share information on the net prices of health products (official/list prices less rebates and discounts)” and to “work collaboratively to improve the reporting by suppliers of sales revenue, prices, units sold, marketing costs, investments and subsidies.”22 Although this resolution is not legally binding, it does underscore the global concern about medicines access, affordability, and access to accurate price information.

Civil society actors in SA have previously used competition law to address alleged abuse of dominant positions in the pharmaceutical market, resulting in prices that were unaffordable. Examples included the cases brought by Hazel Tau and others against GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim, and by the Treatment Action Campaign against Bristol-Myers Squibb, which resulted in access to more affordable, generic antiretrovirals.23 It was emphasised that manufacturers could justify their prices by being transparent about the costs of research and development, production costs, and reasonable returns on investment. In this dialogue, representatives from the competition authorities indicated that they had been requested to investigate cases where a company registers a product but does not supply it (referred to as general exclusionary conduct). However, they pointed out that the SA legal system is slow paced and the challenge of accessing pricing information from manufacturers that are based outside of SA. Participants indicated the need for a global repository of accurate medicine pricing data. Finally, participants acknowledged the ongoing problems with the patent system in SA, which lacks an effective patent examination step linked to clear patentability criteria.

Evidence informed selection of oncology medicines

In the public sector, oncology medicines are listed in the tertiary/quaternary EML, and can only be accessed by cancer specialists in certain hospitals. Evidence-based selection for accelerated access pathways may face problems with reliance on surrogate outcomes in clinical trials in cancer. An invited speaker from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)24 described the scale developed to evaluate oncology therapies, using a well-validated, unbiased, and disciplined approach to data interpretation. This allows for a reliable and fair evaluation of clinical benefit, assisting in resource allocation decisions by medicine selection committees within countries, and helping to prioritise treatments with higher anticipated benefits. A second speaker described how the selection of oncology medicines that provide substantial benefits is prioritised in Pakistan, and which strategies are employed to make these medicines as accessible as possible. In addition to relying on lower-priced biosimilar trastuzumab options for patients with breast cancer, oncologists in Pakistan also used shorter course treatment (9 weeks, or 6 months from published studies25–27), which reduced the risk of cardiotoxicity with a small reduction in benefit.

Participants debated the idea of being able to use real-world evidence or post marketing surveillance evidence to adjust doses and durations, and thus reduce treatment costs. Good quality evidence would be needed if potential patient harms are to be avoided. Participants also debated the challenges of ensuring access to the necessary diagnostic capacity to make the best use of oncology medicines. Considerations of budget impact would be critical to the selection of affordable diagnostics and therapies.

Pooled procurement options

The final dialogue looked at pooled procurement, which seeks to exploit the monopsony power of combining a number of different buyers. Two invited speakers from the WHO described the development of a pooled procurement system for childhood cancer therapies, to be funded by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Significant inequities in access have been shown between countries, even though the incidence of childhood cancer is consistent across different cancer types and across different communities. The project plans to leverage existing centralised procurement structures, such as the United Nations Children’s Fund and the Pan-American Health Organization Strategic Fund. Such an effort requires overcoming a number of legal complexities and governance issues. A key lesson learnt was that having a guaranteed source of financing was crucial. Ensuring coherent and co-ordinated national treatment policies is also critical.

Although pooled procurement has been proposed in the Southern African region, there are legal and regulatory barriers to its implementation. In this regard, the African Medicines Agency holds the potential to improve harmonisation of regulatory systems on the continent.

Finally, all participants felt that having such discussions with the NDoH and its provincial counterparts on a regular basis would help in implementing access solutions for high-priced oncology medicines in both sectors. Solutions could also be implemented in collaboration with the private sector and civil society, as a shared responsibility.

Discussion

Most countries have a mechanism to allow access to unregistered medicines on compassionate grounds or to treat patients with special needs. In SA, although section 21 of the Medicines and Related Substances Act of 1965 (as amended)8 provides that access, it is silent on the pricing of such products and the need for transparency for these arrangements. These medicines fall outside the remit of the SEP provisions, as unregistered medicines that are not required to have a declared launch price. Attention is needed to this lacuna in the law. The Cancer Alliance is reviewing the legal framework to identify provisions in the legislation to allow for alternate pricing arrangements and access to high-priced and ‘abandoned’ older medicines. In addition, both the Pricing Committee and SAHPRA have previously had discussions on this issue (based on authors’ knowledge). It is not known whether these are continuing or whether any legal advice has been sought.

Globally, increasing attention is being paid to transparency in medicine pricing. Apart from the World Health Assembly Resolution 72.8, courts in a number of jurisdictions have ruled on access to prices and procurement contracts.28–30 The Spanish Council of Transparency and Good Governance (Resolution 079/2019) stressed that it is critical to understand the decision-making process of policymakers that affect public health and its financing.29 This council stressed that it is a democratic right to access public information. France and Italy have both created legal requirements for pharmaceutical manufacturers to disclose the extent of public investments in research and development of new medicines when applying for reimbursement. In the WHO European Region, 15 countries use publicly accessible online platforms to publish several types of medicines prices.29 South African private sector prices are made visible, even though the components of the SEP are not entirely transparent. However, to date, little research has focused on the impact of these transparency provisions on access to medicines or pricing of medicines. The discussions with participants viewed this as a negative aspect. The key issue remains: to whom should prices be made transparent and how?

In SA, the NCSF7 recognises the importance of the EML process and the rigorous evidence-based approach that is used to develop STGs and select medicines for the public sector. Although the policy points to the unaffordability of many oncology medicines, little is said about the access strategies or pricing policies that could be employed to improve access. The NCSF does not consider the problem of the pricing of unregistered medicines accessed via section 21, nor how to ensure continued access to older medicines which are no longer marketed in SA. The participants explored ways in which section 21 applications could be improved and made more transparent. The next review of the NCSF should also consider how alternate pathways to access by patients are made transparent. Whether effective incentives for pharmaceutical manufacturers can be found to ensure that needed medicines are registered in SA, and subsequently marketed, remains to be seen.

Since the completion of the dialogue sessions, lenalidomide was added to the EML in 2022 and the latest tender was awarded at a tender price closer to the actual manufacturing cost of this medicine.31 In addition, as of 19 February 2024, the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention approved a pooled procurement mechanism for medical products from the African markets. This potentially holds promise to improve equitable and affordable access to high-priced medicines.32

This study faced some limitations. While the selected participants were representatives of the pharmaceutical supply value chain, and reflect those that play a role in access to high-priced oncology medicines, some voices may have been missed, and therefore, some challenges and solutions may not have been explored. In addition, the focus was largely on high-priced medicines, not the entirety of the health systems challenges facing the provision of comprehensive and effective oncology care.

Recommendations

Based on outcomes of the Solution Labs, the following recommendation were developed:

-

The NDoH should explore other pricing tools, such as negotiations, volumes, and discount arrangements to make more oncology medicines available to patients in the public and private sectors, and in time for National Health Insurance. Current legislation should be reviewed to identify possible amendments which would enable specific pricing policies for high-priced medicines.

-

There needs to be a global repository that collects all components of pricing information from different countries to be able to make meaningful price comparisons possible. SA should work with the WHO on this issue, in collaboration with other African and low- and middle-income countries.

-

The NEMLC should consider using good quality real-world evidence, in addition to data from meta analyses or randomised controlled trials, in devising affordable treatment guidelines for cancer. These could be local (if available) or adapted from other countries (such as the European Union) that are making this information publicly available.

-

When considering pooled procurement opportunities, care should be taken to address regulatory harmonisation across participating countries. There are important lessons to be learnt from other regulatory harmonisation and task-sharing arrangements, such as Zazibona33 and BeNeLuxA.34

-

SAHPRA, in conjunction with NDoH, should review the current section 21 guidelines to include attention to the prices offered (e.g., requiring at least three supplier quotes, where available, and lead times), so that patients and their prescribers can exercise informed choices based on the urgency of their treatment. The outcomes of section 21 approvals also need to be available in a transparent manner to other prescribers and patients via the SAHPRA website and/or email distribution lists set up by SAHPRA.

Conclusion

There is a clear need for a national forum where all stakeholders in this field can engage in discussions with the NDoH and its provincial counterparts, to find solutions to the oncology medicines access conundrum. Reviewing access to medicine policies regularly, as well as challenges experienced within the healthcare system, in collaboration with private sector and civil society, will improve access to these medicines.

Acknowledgements

Paul Malherbe, Economic Consultant, Cancer Alliance, South Africa, for his assistance with Figure 1.