Introduction

South Africa is characterised by high levels of poverty, interpersonal violence, and a societal history of trauma, all of which are associated with a higher risk of mental health disorders. Studies have shown strong links between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as sexual abuse; physical abuse; neglect; family dysfunction; and domestic violence; and increased risk of psychological outcomes during adulthood.1–4 Recent social and economic struggles in South Africa have exacerbated this overarching environment, feeding into the rise of mental health disorders and closely associated problems like substance abuse.1,5 While positive parenting is protective against the impacts of ACEs,6,7 a negative early parental experience makes the child more vulnerable to their detrimental impacts,8,9 such as increased risk of learning and behavioural problems at school, chronic depression in adulthood, suicide attempts, drug and alcohol abuse,10,11 and many other detrimental long-term outcomes.12,13

Mental health disorders are increasingly being recognised as a major contributor to global disease burdens worldwide,1,14 with an associated need to focus on improving chronic care systems. Marais and Petersen, like others,1,15 have argued that “[i]ntegrating mental health into chronic care services, particularly at the primary health care level, is likely to lead to improved medication adherence and lower healthcare costs in low- and middle-income countries.”14 In South Africa, the Primary Health Care (PHC) system has historically not incorporated mental health services adequately.14,16 The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023─203017 reflects a strong commitment to addressing this gap, outlining how the district mental health system will be strengthened, including through routine screening for mental illness during pregnancy and other identified high-risk group services, such as those targeting schools.17 The Plan acknowledges that there are shortfalls in the availability of human resources for mental healthcare, including mental health practitioners. By making moderate changes to the current PHC system, major improvements in mental health services could be made, which would benefit patients, including substance abuse cases.1

Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in South Africa are a key population in terms of their high risk of contracting HIV.18 Along with the many social determinants of HIV risk, such as entrenched poverty and inequality, is their exposure to ACEs, including many of those already outlined. AGYW have thus become a specific focus for HIV prevention efforts designed to address a range of risk factors. One such leading initiative is the multi-country Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe (DREAMS) programme, which is implemented by a number of partners, including the non-profit organisation TB HIV Care (THC) in South Africa. While the DREAMS model is comprehensive in nature, THC identified the need to develop a specialised mental health intervention for AGYW, to further strengthen the programme’s ability to protect them from HIV.

This paper explores this innovative mental health model which THC developed in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape. It argues that this approach not only strengthens efforts to protect AGYW from the risk of HIV, but also provides lessons for the government as it seeks to address weaknesses and gaps in mental health services for the general population. It recommends that such approaches should be better integrated into the PHC system, especially to reduce the impact that mental health disorders have on young people.

Case description

DREAMS was launched in 2014 by the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The programme offers layered and multi-dimensional HIV prevention, incorporating a combination of structural, behavioural, biomedical, and psychosocial interventions aimed primarily at AGYW aged 10─24. This core package of interventions targets the social, cultural, behavioural, economic and biomedical vulnerabilities that place AGYW at greater risk of HIV infection. Between 2019 and 2025, THC was funded to implement DREAMS in four districts in KwaZulu-Natal and one in the Eastern Cape.

In addition to addressing the core vulnerabilities facing AGYW, THC identified mental health as a major area needing fundamental support, not least because of the high numbers of its AGYW clients reporting the experience of ACEs and the alarming rate of substance abuse. THC consequently developed an innovative mental health component which seeks to support AGYW and reduce their risk of various negative outcomes, including contracting HIV. THC, with the support of its funders, collaborated with Brown University, the Foundation for Professional Development, and the International Technology Transfer Centre at the University of Cape Town to develop its mental health component.

Method

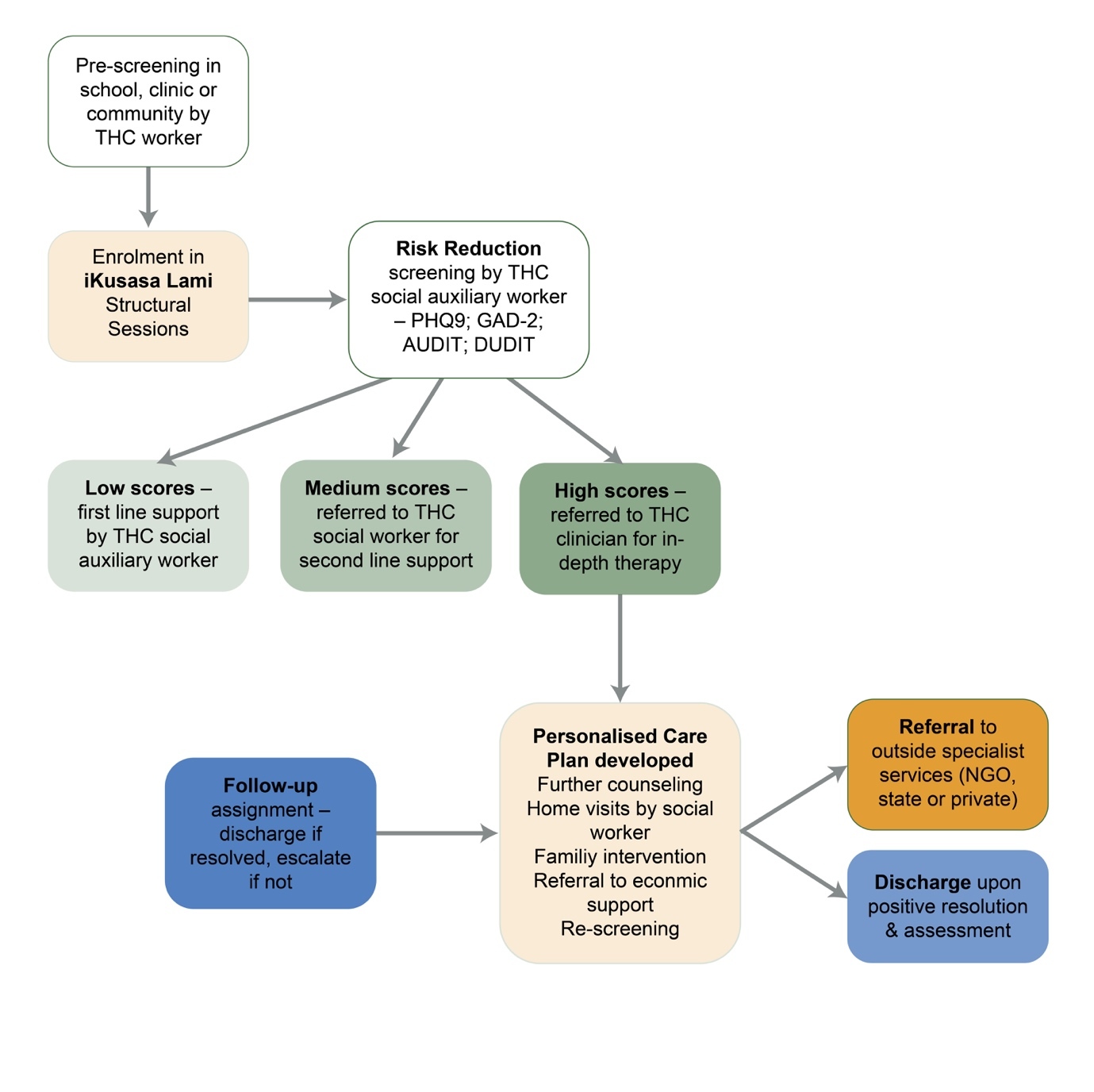

The approach adopted by THC involves their multi-disciplinary teams (i.e. structural programme facilitators, biomedical and economic support, and psychosocial personnel) targeting clusters consisting of identified schools, health facilities and community venues within their districts of operation. Each district has several clusters through which programme beneficiaries are recruited and offered services. The entry-point for the programme is the 14-session, age-appropriate iKusasa Lami (‘our tomorrow’) structural sessions comprising educational modules focusing on HIV, violence prevention, social asset building, and financial literacy. The programme is delivered to groups of AGYW in schools, health facilities, or community venues.

Effective screening

On sign-up for the programme, an initial pre-screening is conducted with each AGYW client. In addition to socio-demographic information and data relating to each client’s health and HIV status, the screening seeks to identify key vulnerabilities such as alcohol abuse, multiple partners, or experiences of abuse, which may need urgent flagging with the psychosocial team – consisting of a social worker and several social auxiliary workers (SAWs). Since most clients come from a context of poverty, with many also experiencing trauma, loss and abandonment, THC then provides a full ‘risk-reduction’ screening for each participant during the course of the structural sessions. Previously, such screening was conducted only on graduation from the 14 sessions, but it is now conducted in batches from session 3 onwards, in order to catch cases quickly. In the early years of THC’s programme implementation, risk-reduction screening was initially conducted by a variety of THC staff, some of whom were not specifically trained in psychosocial support. This approach was discontinued when it was realised that screening is more effective when conducted by trained psychosocial staff.

The electronic risk-reduction tool

The risk-reduction tool used to screen clients for mental illness is an electronic form loaded onto a tablet computer belonging to the SAW. The tool is comprehensive, identifying and scoring a wide variety of key vulnerabilities relevant to AGYW including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, alcohol and drug abuse, sexual risk, and mental health issues. The tool is made up of the following components:

Pfizer’s Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Used to determine depression and its severity, this forms the bulk of the risk-reduction tool.19 The questionnaire asks clients to answer nine questions relating to how they have felt over the preceding two weeks in terms of mood, energy, appetite, sleep, self-esteem, and suicidality. A tenth question asks them to assess how difficult these problems have made doing their work, taking care of things, or getting along with people. Questions 1 to 9 have an associated score, with values ranging from 0 to 3. For questions where the ‘not at all’ option is selected, 0 is allocated, whereas 3 is scored if the problem has been experienced ‘nearly every day’. These scores are totalled to provide an overall score at the end of the PHQ9 form.

General Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2)

This form20 is also incorporated and asks two questions related to anxiety, with scores depending on the answers.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)21 and Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT)22

To ascertain substance and drug-use, questions from both the AUDIT and DUDIT tests are incorporated into the risk-reduction tool.

The risk-reduction tool also includes questions about experiences of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and clients’ sexual risk profile. The questions in this tool are used in their original form, as they are deemed relevant to the target population. Although they are presented in English, the SAWs who administer the tool translate the content as necessary into local languages (isiZulu and isiXhosa).

Triage and referral system

The SAWs who have been trained to provide first-line counselling using the LIVES (Listen, Inquire, Validate, Enhance safety, and Support) method, and to carry out this screening with each AGYW, taking about 20 minutes per client. Although the risk-reduction tool does not provide a full picture of the mental health status of a client, it automatically calculates their need for assistance based on their scores, and recommends the action that is needed:

-

0─4 (low risk)

Indicates the absence of depressive disorder, but in some instances the client may need support from the SAW. -

5─9 (mild risk for depressive disorder)

The clients are supported by the SAW or THC social worker for more in-depth investigation and counselling. -

10─14 (moderate risk)

In addition to clients scoring between 10 and 14 on the PHQ9, those answering ‘yes’ to the suicidality question, or who score 3 or more on the GAD-2 questions, are counselled by the social worker and if necessary, referred to a clinician employed by THC for in-depth assessment and therapy. -

15 and above (moderately severe or severe risk)

This indicates major depressive disorder and these clients are prioritised by the THC clinician, or referred to specialist services.

Figure 1 shows the mental health model developed by THC.

Results

Enabling a mental health support cascade

The result of this screening system is the enablement of a mental health support cascade. Table 1 shows screening data and consequent referral pathways of the psychosocial team for various degrees of mental health risk identified between October 2022 and May 2024. In a 19-month period across all five districts, 145 605 mental health screenings were performed, of which the vast majority (95.5%) returned a low score (PHQ9 score of 1─4). The uMgungundlovu and Zululand Districts had the highest proportion of positive mental health cases identified (11% and 7%, respectively), most of which were in the mild or moderate risk category. THC conducts repeat risk-reduction screening throughout the time it works in schools to ensure that mental health issues are picked up. Table 1 shows how just over 5 000 clients were identified for first-line counselling by SAWs for low-grade mental health needs; 934 were identified for higher-level support from the social workers for moderate to severe needs; and 506 moderately severe and severe cases were referred to the clinician for further action. Severe and moderately severe cases involved depression, anxiety, various forms of abuse and violence, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse, among others.

Moderate cases referred to social workers receive a follow-up consultation, which includes a home visit where possible. Not only is second-line counselling provided at this point, but efforts are made by the social worker to address the root causes of depression and anxiety as well as factors which may exacerbate or result from them. These may include substance abuse, unemployment, abuse, neglect, relationship problems, or problems at school. Referral to partners such as the Thuthuzela Centres which are government multi-sectoral facilities dealing with sexual violence, or to organisations addressing drug addiction, are also undertaken by the social worker. Clients raising concerns on AUDIT or DUDIT questions are dealt with by the social worker, and if there is a significant mental health problem, they will also be seen by the clinician. If a substance use disorder is indicated, they may be referred to a proven rehabilitation facility or support group. The social workers will also involve the family in offering support. Such cases need a comprehensive care plan including the possible provision of methadone or other medications, family therapy, meaningful work or livelihood opportunities, and ongoing psychosocial support.

Moderately severe and severe risk cases identified are referred to THC’s clinician, who works across all five of THC’s DREAMS districts. The clinician visits each district in a monthly cycle, seeing accumulated referrals wherever they are available ─ commonly in schools, tertiary education centres, community centres, clinics or in homes. The approach is flexible, AGYW-centred, and context-appropriate. While the clinician is unable to visit every identified client, social workers intervene in some cases, or refer them as needed.

In consultations, the clinician looks for a wider range of diagnostic entities than the risk-reduction tool can identify. These include psychosis, bereavement disorder, dissociation, personality traits and disorders, mental disability and physical illness. The clinician also attempts to identify underlying causes and vulnerabilities, and then offers appropriate therapies, including solution-focused therapy, trauma counselling, and even faith-based counselling where appropriate. The fundamental aim of the intervention is to restore the proper balance between the rational and emotional brain functions, so that the client can feel in charge of how they respond and conduct their lives, instead of being triggered into states of hyper- or hypo-arousal. The team thus works to address post-traumatic stress and the ways in which this is remembered in the body.3

Under ideal circumstances, all of those identified with mild risk or higher would be seen by the district-based psychosocial teams. However, THC’s small teams are unable to support every case due to time and resource constraints. They therefore have to prioritise the more severe cases. While THC’s tracking system was not fully developed in 2022 and 2023, more recent tracking data shows that in 2023 and 2024, around 10% of mild-risk cases were seen by SAWs; 38% of moderate cases were seen; 39% of moderately severe cases were seen by THC’s social workers; and 56% of severe cases were seen by the clinician. For the more severe cases, clients were referred to other services where it was not possible for THC to see them. THC’s recent focus on supporting school-based learner support agents (LSAs) has also allowed for an increasing number of mild risk cases to obtain a basic level of support at school, thereby freeing up other psychosocial staff to address the more serious cases.

Personalised care plan and follow-up system

When the clinician has worked with severe risk clients, they will then report back to the psychosocial team and together they develop a care plan for the client. This care plan is individualised for each client, acknowledging that social and economic support is essential to recovery, and taking account of adverse childhood experiences and associated trauma. The plan thus takes into account diagnosis, social support, ongoing trauma, safety issues, risk, resilience, the need for medication, and external referral. The latter may include referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist, other mental health support, the Department of Social Development, faith-based organisations, or other community support services. Certain cases are also referred to THC’s intensive economic support interventions.

Online tracking system

THC has developed an online application containing the risk-reduction tool, which includes the ability to conduct further assessments with clients during implementation of the care plan. This allows the psychosocial team to obtain follow-up scores and track change over time. The team assesses improvement through administering these tools, as well as other observations made during follow-up visits. The social worker and clinician listen to, engage with and observe the client, and speak to her family members or supporters to ascertain whether she feels safe and calm; if she can maintain this state; if she can engage with others; if she feels fully alive; whether she can share secrets with herself and others, and whether her PHQ9 and GAD-2 scores improve. Clients who have experienced chronic trauma are at risk of ongoing vulnerability despite therapy and support. The capturing of these data on the psychosocial app allows THC teams to monitor follow-up over time and reduce vulnerability. The follow-up process also allows the psychosocial team to maintain contact with the client and support them in various ways which contribute to their recovery. Unfortunately, the development of this online tracking system was completed only in late 2024, so data-tracking outcomes (e.g. follow-up PHQ9 scores, reductions in other risk factors) for the cohort presented in Table 1 are not available. However, anecdotal evidence from the case reports of SAWs, social workers and the clinician indicate that their interventions typically lead to a positive outcome.

Discussion

Early and effective mental health screening for key populations like AGYW is critical to ensure early detection and intervention. On the face of it, the very high proportion of low-risk cases identified in THC’s screening (95.5% with scores under 4) appears encouraging, given the circumstances in which most AGYW have grown up. However, other studies which have used the PHQ-9 tool with similarly positioned AGYW in urban South Africa have found much higher proportions of clients (up to a third of those screened) with scores of over 10.23,24 Given that the PHQ9 tool has been found to be suitable and effective for identifying depression and anxiety among South African AGYW,25 THC’s low number of positive mental health screenings may thus reflect the high stigma associated with mental health, especially in rural areas, or some inadequacies in THC’s initial approach to screening in 2022 and 2023. Indeed, THC’s experience has shown that screening is best done by properly trained psychosocial support workers, as when lay staff, such as peer educators, initially conducted the screening, fewer mental health clients were identified than when SAWs did the screening.

The tools also need careful consideration. THC’s risk-reduction tool, which incorporates PHQ9, GAD-2, AUDIT and DUDIT, is a good model, but may need further adaptation for and validation by the specific AGYW targets of the intervention. Moreover, to enhance the relevance of the diagnostic categories for AGYW, the acceptance of developmental trauma disorder,25 which is more representative of AGYW issues, might assist to more effectively address the root causes of disorders and offer appropriate treatment and care.

THC has also found that AGYW are much more likely to be open during screenings when they have participated in the structural sessions, and are more aware of their own health issues. This suggests that mental health screening should take place in conjunction with other support programmes, such as the educational and peer-support programmes provided in DREAMS. This is particularly important in the cultural contexts in which THC works, where mental health issues are still highly stigmatised, complicating disclosure and treatment. It emphasises the need for trained workers to conduct screening, with sound tools and a relational and educational context in which to conduct screening.

Another important area of learning is in the treatment of identified patients. THC’s support cascade and care planning work well for the majority of cases whom they are able to reach, and clients are assisted according to their needs. THC’s social workers and the clinician have reported that low and moderate cases respond well to the counselling and support they receive from the SAWs and social workers. Unfortunately, until recently, THC was not able to track systematically the other indicators of positive care outcomes, such as client satisfaction, reduced screening scores, or negative HIV status. However, the fact that THC struggles to see all identified mild-risk and moderate-risk cases is an impediment, especially in relation to catching and addressing such cases before they become more severe. This emphasises the need to incorporate such a screening and treatment cascade into larger and more resourced public health systems, so that early detection and treatment can be effective.

Severe cases also respond well to the more intensive support of the clinician, as demonstrated by falling screening scores in follow-up visits and subsequent discharge. Others are referred to more specialist services. However, because of the difficulty of addressing trauma using conventional therapies, additional treatment modalities should be considered, including mindfulness, yoga, music, movement, rhythm and action. However, resource constraints and large travel distances make offering such therapies to clients difficult, even for THC’s teams. It is therefore crucial that sound referral and continuum-of-care pathways are established with other partners who can provide these specialised trauma and substance abuse therapies. THC itself is not funded adequately for this psychosocial aspect of its work, so it is unable to expand its services by, for example, recruiting more psychosocial staff, or purchasing more vehicles for care follow-up. The high mobility of AGYW clients also presents a major challenge for anyone attempting to implement care plans with such clients, and there are very few other organisations to which clients can be referred.

While the PHC system may not be able to go to such lengths in treatment, the expansion of screening at health facilities, schools and community venues using the mental health screening tools described would be a major step forward in identifying mental health risks and disorders, especially among AGYW. First-line support and treatment could be provided by trained health workers and other cohorts of school- and community-based workers. Through the provision of effective referral pathways, more intensive support could also be developed using multi-sectoral partnerships with non-State service providers, as suggested by the latest government policy framework.17 Non-governmental organisations such as THC, in partnership with the Department of Health (DoH) and others, could also explore innovations such as digital mental health screening tools and case-management solutions.

This paper has provided an example of a model which is being tested and refined to ensure that the best possible approach is adopted. While many challenges have been faced in providing the reach and scale needed to care for identified cases, the lessons that THC has identified suggest the following recommendations.

Recommendations

Based on the lessons from this practice case, the following recommendations for policy-makers and public health role-players should be considered:

-

To fully realise the aims of the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023─2030, a model similar to that developed by THC for mental health screening, referral and treatment should be adopted into the PHC system in South Africa, especially focusing on the most at-risk populations such as AGYW.

-

As this case demonstrates, mental health screening can be integrated into existing HIV prevention efforts targeting high-risk populations such as AGYW in community settings such as schools. This could have major systemic benefits, including reducing the burden on PHC facilities, improved community awareness, and reduced mental health stigma.

-

A similar electronic tool incorporating all the questions used in THC’s DREAMS risk-reduction screening and a similar scoring and triage system should be adopted at PHC level. Questions should be adapted, validated and translated for specific populations.

-

Based on lessons from THC’s DREAMS implementation, healthcare and other outreach workers should receive targeted training in order to ensure that the screening tools can be used effectively and that they can provide effective first-line support and referral services.

-

Where possible, mental health screening should take place in conjunction with other support and health education programmes, for example, in schools, youth clubs or postnatal support groups.

-

Since the DoH cannot provide all specialist treatment services, sound referral and continuum-of-care pathways should be established with other government and non-government partners who can provide specialised trauma and substance abuse therapies.

-

More research is needed on the outcomes of the care plans for clients with all levels of mental health risk.

Conclusion

Given the pervasiveness of ACEs among vulnerable populations, and consequences such as mental health conditions and substance abuse disorders, it is vital that mental health screening is properly incorporated into routine health services. THC has developed and tested a mental health screening and referral model with a vulnerable population of AGYW. This paper provides lessons from THC’s implementation of this model, which can help the government to address weaknesses and gaps in existing mental health services. It provides a range of recommendations not only on how to incorporate this model into existing public health systems, but also on how to strengthen it so that health workers can accurately screen patients and identify various risk categories of mental health, and refer them for appropriate and timely intervention. The adoption of this model could assist the government to properly implement the aims of its current Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan.