Introduction

Mental health challenges are among the most critical health issues facing young people in sub-Saharan Africa, but resources for mental health in the region are scant. Across 37 recent studies, adolescent prevalence rates in sub-Saharan Africa were estimated at 26.9% for depression, 29.8% for anxiety, and 40.8% for emotional and behavioural problems.1 In South Africa, a 2016 study found that 41% of adolescents experienced depression, 16% anxiety, and 21% post-traumatic stress disorder.2 Despite this burden, there is a severe lack of resources and trained, accessible providers in sub-Saharan Africa.3 Only about 5% of South African health spending is devoted to mental health,4 and fewer than 10% of those needing mental health care or treatment in the region will ever receive it.4

Adolescence is a critical period for mental health development and intervention. Nearly 50% of adult mental health conditions onset by age 14,5 and 75% onset by the age of 24 years.6 Adolescents with mental health problems have more difficulty with social relationships and school and work performance.7 Mental ill health also has implications for other health challenges, such as sexual and reproductive health issues (e.g. unintended pregnancy, gender-based violence, and HIV).8,9 Adolescence is an important period for intervention since adolescents develop lifelong health-related behaviours and habits as they take greater responsibility for their health.10 Without early intervention and treatment during adolescence, mental health conditions accrue additional comorbidity once they persist into adulthood.11

The opportunity for early intervention in adolescence through mental health promotion and prevention programming is immense. Group- and community-based programming can help promote positive mental health and prevent mental health challenges in young people. School- and community-based interventions can improve emotional and behavioural well-being, self-esteem, motivation, and self-efficacy,12 and interventions that address interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and alcohol and drug education can have significant effects over multiple outcomes.13 Universally delivered interventions, rather than those targeting only adolescents experiencing challenges, are recommended.14 Non-specialist lay providers can be trained to implement these interventions at community level, reaching more adolescents and supporting them in building positive mental health and social-emotional competencies.15

In South Africa, there is growing recognition that mental health promotion and prevention programming can help break the cycle of poverty and mental ill health by building resilience and improving self-regulation in environments full of mental health risks.16 The South African National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023─2030 recognises the importance of mental health promotion and mental illness prevention in key developmental stages, including adolescence, highlighting it as an area for action.16 The Strategic Plan additionally highlights opportunities within the education sector to improve screening and referral processes, integrate mental health literacy education into subjects such as Life Skills and Life Orientation, and train school-based support teams on mental health education to better support learners.16

Grassroot Soccer (GRS) began implementing soccer-based health programmes for youth in 2002, with a focus on HIV prevention. GRS programmes utilise a positive youth development approach that emphasises fun and activity, relatable caring ‘coach’ mentors from the community, and evidence-based programme content. GRS ‘SKILLZ’ programming has shown effectiveness in improving adolescent health knowledge, building resilience and self-efficacy, and increasing uptake of health services.17–19

In 2022, GRS developed a mental health strategy to integrate mental health content into existing SKILLZ programmes. This paper presents learnings from integrating mental health content into sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) programmes. Specifically, it: 1) documents the process of adapting the curriculum and providing training on the new curriculum content; 2) presents preliminary results based on programme monitoring data, and 3) shares challenges faced and addressed by GRS. From these experiences, we reflect on challenges faced while integrating mental health content into SRHR programmes and how GRS has addressed these challenges.

Case description

Setting: Alexandra

GRS operates in Alexandra, Johannesburg, where programmes are delivered at local schools and community sites, and a community football centre run by GRS. Alexandra (‘Alex’) is a vibrant, youthful, and diverse community that grapples with socio-economic challenges impacting mental well-being across all age groups. Housing is often substandard, lacking basic amenities and sanitation. Schools are often overcrowded and under-resourced,20 and only 39% of learners have matriculated by age 20.21 Crime and violence are also common, especially gender-based violence.22

Adolescents growing up in Alex face significant challenges to their health and well-being. Community and household socio-economic status are strong predictors of the prevalence and severity of mental health conditions.23 People in poverty are at increased risk of mental health disorders, and those with mental health challenges are at increased risk of social exclusion and losing employment and housing.24 Experiences of childhood adversity in South Africa have been significantly associated with mood disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder.25 Youth are affected by poor mental health due to continuous high stress, unequal opportunities, poverty, exposure to drugs and alcohol, teenage pregnancy, and lack of parental emotional and mental support. As in most of South Africa, there are few mental health professionals in Alex, leading to high demand for the under-resourced public services, as residents often cannot access private mental health services without assistance.26

Considering the limited resources and services available to support adolescent mental health in Alex and throughout South Africa,16 GRS takes an approach of positive youth development to develop young people’s social and emotional learning (SEL) competencies. Building foundational social and emotional competencies positively affects multiple health and development outcomes, including relief from depressive symptoms, reductions in perpetration of violence and bullying, and reduced use of alcohol and other substances.27

GRS’s approach to youth mental health focuses on positive development by building on young people’s existing strengths and relationships. This approach recognises that young people are more likely to thrive when they feel competent, connected and empowered. The skills covered in GRS adolescent mental health programming are beneficial across multiple health areas. Instead of merely addressing problems or focusing on a single issue, a positive youth development approach is essential for fostering overall well-being.

GRS’s SKILLZ programmes

GRS implements multiple programmes under the umbrella brand ‘SKILLZ’ that are tailored for different segments of young people: ‘SKILLZ Girl’, initially developed in 2010, targets adolescent girls aged 15─19; while ‘SKILLZ Guyz’, first implemented in 2017, targets adolescent boys age 15─19.

The SKILLZ approach is built on a model of 3Cs:

-

Curriculum: adolescent-friendly, evidence-based health curricula use soccer language and activities to convey health concepts and spark important discussions.17

-

Coaches: ‘Caring coaches’ are near-peer mentors, trained in youth facilitation skills and health content to be positive role models. Coaches are recruited through a competitive process and must have completed high school. GRS staff train coaches on evidence-based skills to engage with youth, including giving effective praise, building personal connections, facilitating vital conversations, creating safe spaces, and conveying accurate health information. These skills draw on youth development evidence on the positive impacts of praise28 and the importance of caring relationships with trusted adults.29 The use of slightly older coaches from the same communities as participants allows participants to model the behaviours of people like themselves.30 Coaches receive ongoing supportive supervision and professional development activities.

-

Culture: GRS programmes emphasise fun, safe spaces that provide engaging, play-based experiences. Programmes include energiser activities, group praise, and interactive discussion to differentiate GRS from other health programmes. GRS culture uses the familiarity of soccer to help young people feel comfortable when discussing sensitive topics and to naturally foster relationship-building.

GRS aims to achieve impact by addressing assets, access, and adherence in adolescents. GRS programmes build youth assets, or skills, knowledge, and capabilities that youth can use to shape their lives.31 GRS also increases youth access to health services, facilitating bi-directional referrals through coaches who help young people to navigate the health system and host community health events with service providers. GRS additionally aims to increase adherence to medical treatment, therapy, and healthy behaviours.

GRS conducts routine monitoring to ensure programme quality and to explore effects on participants. Attendance data are captured at every programme session, and a sample of participants takes a brief pre- and post-intervention survey to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. Routine monitoring data, particularly the pre- and post-surveys, also help to inform curriculum revisions.

The GRS SKILLZ approach and impact model was developed to guide SRHR-focused programmes such as SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz, articulating the GRS positive youth development approach. Prior to 2022, this approach supported the well-being of young people without explicitly addressing mental health as a key focus area.

Method

Development of GRS’s mental health strategy

As a first step to integrating mental health into existing programmes, GRS developed a mental health strategy in 2022. Through consultations with staff, mental health experts, and young people, GRS built on institutional knowledge and experience to articulate strategic priorities and develop a theory of change. Key principles of GRS mental health work state that it is:

-

Grassroots-driven: co-developed alongside young people.

-

Relationship-focused: nurturing positive relationships between adolescents and trained coaches that create safe spaces and open dialogue.

-

Powered by play: using play and fun to enhance social-emotional learning and ease fears around discussing mental health.

-

Strengths-based: supporting adolescents to build upon their existing skills, assets, and strengths instead of ‘fixing deficits’.

-

Provides supportive environments: engaging with parents, teachers, and other people in adolescents’ lives to de-stigmatise mental health.

-

Trauma-informed: following best practices by providing safety, trustworthiness, play, peer support, empowerment, and collaboration.32

-

SEL-aligned: building SEL competencies such as forming strong relationships, managing stress, and regulating emotions.

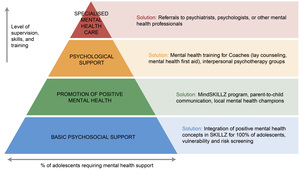

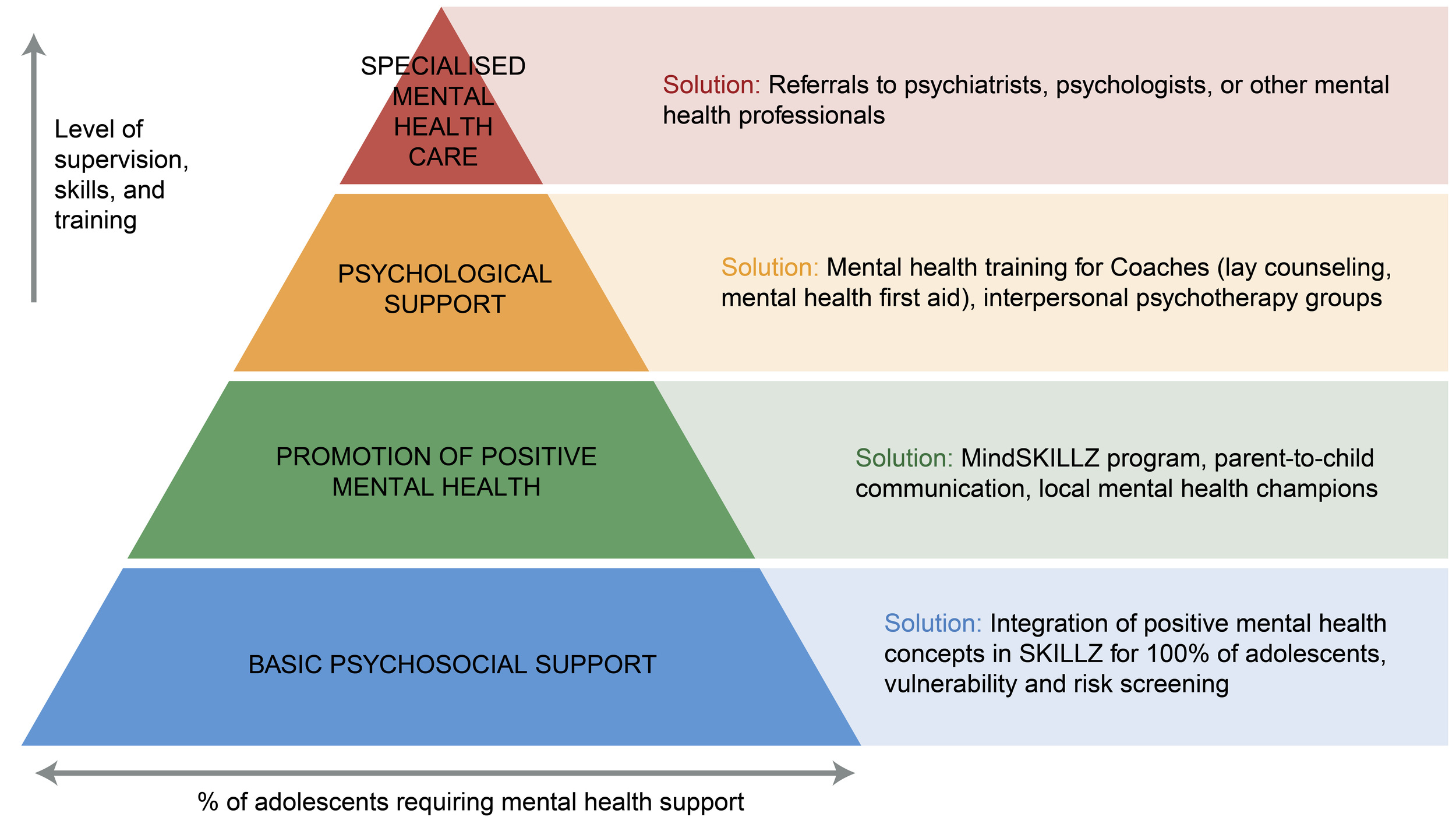

A critical component of the GRS mental health strategy is alignment with best practices for providing mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) in resource-limited settings. GRS adapted the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s MHPSS intervention pyramid, which shows layers of support for mental well-being33 (Figure 1) similar to the services organisation pyramid highlighted in the National Strategic Plan.16

GRS focuses on the lower pyramid levels to provide basic psychosocial support and build mental health awareness. The focus at the lower levels, especially ‘basic psychosocial support’, is based on two premises: 1) all adolescents can benefit from basic support when it is integrated into adolescent health programmes, and 2) GRS coaches can be easily trained to provide this level of support through layering onto existing training.

GRS’s approach to integrating mental health into existing SRHR programmes

Integration of positive mental health promotion into existing programmes has multiple potential benefits. It not only introduces the topic to all beneficiaries and supports building basic coping skills, but it also allows programmes to continue addressing other key health topics for young people, such as SRHR topics, healthy relationships, HIV prevention, and communication skills. In 2022 and 2023, GRS undertook this integration process with the SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz programmes, implementing the programmes with adolescent participants.

The integration approach GRS took for SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz in Alexandra included the following key activities:

-

Adaptation to the curriculum and its delivery: GRS staff reviewed the existing curricula for SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz as starting points. One focus group discussion was held with eight SKILLZ Girl coaches to hear their perspectives on curriculum revisions and programme delivery recommendations. GRS also invited staff from implementing partner organisations to participate in a participatory curriculum review and design workshop alongside male adolescent participants. In the workshop, attendees reviewed existing topics in SKILLZ Guyz, suggested new ones, and helped in brainstorming how the topics should flow. Changes to curricula were documented in memos and reports, and curriculum frameworks were clarified to align with the overall mental health theory of change, and guide the development of routine monitoring tools and processes. Locally available MHPSS services, though few, were identified for potential referrals.

-

Training of GRS staff, partners and coaches: Training staff and partners is a critical activity in the integration process, since levels of mental health knowledge, attitudes, and perspectives differ. GRS trained key staff through discussion-based sessions, encouraging team members to reflect on their ideas about mental health and how it impacts adolescent well-being. GRS also conducted two five-day trainings of SKILLZ Guyz and SKILLZ Girl coaches covering the revised programme content and facilitation skills. SKILLZ Girl coaches who were trained before integrating mental health content attended a one-day MHPSS training to build their capacity to facilitate mental health content and familiarise them with locally available services.

-

Delivering programmes and collecting routine programme monitoring data: GRS implemented the revised SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz programmes in Alex beginning in 2022 and collected monitoring data for each intervention group. Coaches took attendance at each session to document participant reach. A sample of SKILLZ Guyz and SKILLZ Girl participants also completed brief 20-item pre- and post-intervention surveys to assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours related to SRHR, mental health, and positive self-concept outcomes. Items in the pre-post surveys were aligned with curriculum content and outcomes in the theory of change. Minor revisions were made to the SKILLZ Girl pre/post questionnaire in late 2023.

Outcomes

Adaptations to the curriculum and its delivery

The review of the existing GRS curriculum highlighted opportunities for integrating mental health into existing activities. Team members recognised the importance of not simply adding mental health content in separate sessions, but incorporating it within existing activities. For example, in a session focused on healthy and unhealthy relationships, mental health was integrated by adding content on how relationships can make us feel, and how they can affect our mental health.

The primary theme in the focus group with SKILLZ Girl coaches was the coaches’ need for mental health support to support youth participants. Coming from the same under-served communities and similar backgrounds as participants, coaches highlighted that their own mental health is essential for executing their facilitation and mentorship roles, as described by one SKILLZ Girl coach:

I shut down certain conversations with participants because I’m scared they will share something that triggers me that I haven’t dealt with.

Coaches also articulated that they needed more training on mental health concepts such as stress, depression, and anxiety in order to convey these concepts to participants effectively. Additionally, coaches stated that their roles as caring mentors necessitated them having more explicit guidelines on their responsibilities and limitations regarding participant mental health support. They highlighted the need for a clear referral system for connecting youth participants to local mental health services where needed. Finally, coaches highlighted a need to continue building their skills and to increase their confidence in delivering mental health content that was new to them. While it was challenging to develop a well-defined referral system for mental health issues, especially in areas with limited mental health providers, the GRS team in Alex reached out to form new linkages, resulting in connections to nearby occupational therapists at a local mental health clinic.

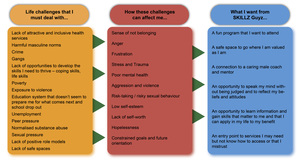

The SKILLZ Guyz participatory design workshop also yielded key takeaways for curriculum revisions. Participants brainstormed and prioritised challenges facing adolescent boys and young men, how those challenges affect them, and the characteristics of an appealing programme that could support them in addressing those challenges (Figure 2). This process helped to highlight and prioritise critical topics to address in the curriculum.

Workshop participants reviewed the existing programme topics and identified those that could be reduced or removed to make space for the mental health content. They brainstormed ideas for new topics and mental health-focused sessions while considering how SRHR and other topics are linked and could be delivered together with mental health content. The resulting curriculum integrated mental health topics such as stress management, emotional regulation, drug and alcohol abuse, and awareness of local MHPSS services. Providing definitions of and information on common mental health conditions was suggested, but ultimately the group agreed to emphasise building skills that promote good mental health rather than defining conditions.

Training of coaches, staff, and partners

Following the completion of the revised SKILLZ Guyz and SKILLZ Girl curricula, GRS conducted multiple trainings of coaches to facilitate the programmes. From September 2022 to July 2024, 38 GRS coaches were trained: 13 young men to deliver SKILLZ Guyz, and 25 young women to deliver SKILLZ Girl. GRS also trained 83 SKILLZ Guyz coaches from three different implementing partner organisations to implement the programme across nine provinces. Finally, four additional trainers were certified to train coaches within GRS and partner organisations so as to increase the GRS training capacity.

Participant reach and preliminary effectiveness

Since GRS integrated mental health content into SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz in 2022, over 4 000 young people have taken part in SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz programming, as shown in Table 1.

Overall, participants in SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz show modest improvement in pre- and post-survey scores, with overall results shown in Table 2.

Table 3 presents results from specific pre- and post-survey items administered to SKILLZ Girl participants, showing modest improvements in basic mental health knowledge, with large improvements observed on select SRHR items examining knowledge of where to access contraception and use of PEP.

SKILLZ Guyz participants showed slightly larger improvements in understanding that stress is a normal part of life, and similar changes in knowledge about the effects of alcohol, as shown in Table 4. Notably, SKILLZ Guyz participants had lower-than-expected baseline knowledge of the risks of multiple sexual partners.

Discussion

GRS continues to integrate mental health content into existing programmes in South Africa and other countries, approaching this as an ongoing learning process. Participant retention exceeding 60% and promising signals from pre/post monitoring data indicate that integrated mental health and SRHR programmes can be feasibly delivered in Alex and potentially scaled. GRS has also developed a stand-alone mental health intervention, ‘MindSKILLZ’, which can be delivered to mixed-gender groups ranging from ages 10─19. Building on the work presented in this paper and recognising the important role of government in these efforts, the GRS team in Alex is actively working with the South African Department of Basic Education to explore integration of its mental health approach into school-based adolescent services.

Through the activities described in this paper, GRS has identified several challenges and limitations that will continue to be ongoing areas for improvement.

Need for further programme refinement to improve knowledge retention

With modest results in knowledge retention, GRS is reviewing the content of both programmes to ensure that they have concise, developmentally appropriate learning objectives and well-aligned content. By ensuring that sessions connect clearly to intended learning outcomes, GRS can increase the likelihood that participants retain what they learn. Additionally, GRS is adding supplemental take-home magazines ─ comic book-style print resources that allow participants to review content at their own pace. The magazines include questions, prompts, space for written responses, and games and puzzles to make them more appealing. Magazines implemented by GRS in other settings have been highly acceptable and have helped participants to start conversations about mental health with friends and family members.34

Limited participant contact time

GRS programmes generally include 10 to 12 sessions, which presents a challenge to covering multiple, complex health topics in an adolescent-friendly way. Partner organisations may request even fewer sessions due to implementation or budgetary constraints, forcing even stricter prioritisation of topics for the curriculum. Demands on adolescents’ time due to schoolwork, household chores and responsibilities, and other activities also pressure GRS intervention sessions. The use of GRS magazines aims to address this challenge while also reinforcing content covered during in-person sessions.

Connecting mental health and SRHR topics

GRS teams initially struggled to identify thematic connections between mental health and SRHR topics in existing programmes. This improved through continuous learning processes, and identifying natural opportunities to connect topics has ultimately improved the logic and flow of integrated curriculum products. For example, connecting healthy relationships to mental well-being may work as a fluid extension. Additionally, GRS has restructured sessions to include a mindful breathing exercise at the start of each session, ensuring that participants learn and practise a coping skill.

Supporting coach mental health

As highlighted in coach debriefings and feedback, many coaches struggle with life challenges and mental health difficulties themselves. In settings with limited mental health service providers, prioritising coach mental health needs can present a greater challenge as they may additionally bear the burden of vicarious trauma from working with participants. GRS has created a safe space through debriefings for open discussion, and has engaged local counsellors to facilitate sessions. GRS is also formalising a coach wellness programme focused on ‘Caring for the Carers’.

Adolescent mental health measurement

The integration process described above used routine programme monitoring tools adapted by GRS. GRS continues to explore best practices in adolescent mental health measurement, aiming to collect informative data from participants that are also meaningful to external stakeholders. These include the use of mental health measurement tools such as the WHO-5 mental health literacy scale, and measures of emotional regulation in research projects, aiming to ultimately include relevant measures in routine programme monitoring. Combined interventions jointly addressing adolescent SRHR and mental health have been relatively under-studied, and few recommendations for integrating mental health into SRHR delivery exist.35,36 GRS hopes to help fill these gaps through continued exploration of appropriate programme monitoring tools and future research. More rigorous research, including longitudinal study designs, will aid in further understanding the effectiveness of integrated mental health content on desired outcomes among adolescents.

Recommendations

Based on GRS experiences, we offer several recommendations for integrating mental health into existing adolescent health programming.

Seek collaboration with multi-sectoral stakeholders to sustainably promote mental health integration

With significant recent reductions in the global funding landscape for adolescent health that directly affect South Africa, particularly from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), it is critical to explore how mental health can be integrated into other well-established services and platforms, such as education, youth development, and health services.37 Implementers, government, civil society, and private sector actors involved in adolescent health and youth programmes should actively seek collaboration on integrating mental health into existing programmes and structures. This could include integrating mental health promotion and prevention activities into basic education curricula, exploring ways to strengthen mental health screening and referrals in schools and youth-friendly SRHR services, and planning adequate funds for integrated mental health activities. GRS is seeking formal collaboration with the South African Department of Basic Education on a teen suicide prevention toolkit, mental health telehealth programme, and mental health literacy training framework for teachers and learner support agents. Additionally, the Global Fund has recognised the importance of integrating mental health into its HIV and TB investments, which presents a timely opportunity to scale up access to integrated mental health programmes through existing health infrastructure.38

Meaningfully engage beneficiaries in participatory design and adaptation processes

Including adolescents and young people representative of participant groups is critical to ensure that programme content and activities are acceptable and relevant to the adolescents who are meant to benefit from them. Adolescent participants and young adult facilitators are valuable human resources who know what works best for them and can provide fresh ideas for natural opportunities to connect mental health with other topics. Pre-testing of activities and content is required to ensure that programmes are fun and engaging.

Prioritise facilitator training and support

Careful planning is required to ensure facilitators are comfortable with mental health content that may be more challenging or new to them. Multiple opportunities to debrief and discuss questions should be included throughout the training. Continued support for facilitator mental health must be carefully considered when planning integrated programmes. Facilitators should have access to a package of support and resources that promotes both self-care and access to mental health services when needed.

Conclusion

This paper presents GRS’s iterative process of integrating mental health into its SKILLZ Girl and SKILLZ Guyz SRHR programmes. Programme monitoring results provide insight into how integrated mental health and SRHR programmes can be delivered by young adult facilitators to improve knowledge, attitudes, and skills in both domains. GRS will continue integrating mental health into all existing SKILLZ programmes in South Africa and further afield throughout 2025 and beyond. GRS recommends that stakeholders in the SRHR and HIV space explore how to integrate mental health content into existing programmes, particularly in the current global health context where low-cost, promotive and preventive mental health models are not only viable, but essential.