Introduction

Mental health conditions in South Africa represent a leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Despite their burden, resources allocated to their prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation are low and disproportionately allocated to centralised, hospital-based care.1

South Africa has a very high treatment gap; recent estimates suggest that 92% of medically uninsured individuals with a mental health condition will not receive treatment.1 The 2018 Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health expanded the concept of the treatment gap to include a ‘prevention gap’ (the gap in coverage of interventions aimed at preventing illness), and a ‘quality gap’ (the gap in the quality of care received by individuals with mental health conditions).2 The disproportional distribution of services means that these gaps are greater for individuals in lower socio-economic communities and rural areas.3

Over the past 50 years, mental health care has shifted towards a human rights-based, recovery-orientated approach, promoting care in the least restrictive environment, as close to home as possible, valuing lived experience and cultural relevance, and advocating for an end to stigma and discrimination.4–7

The World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed a tiered system of care which recommends limiting long-term specialist hospital-based care, while simultaneously strengthening services in general hospitals and community health centres, supporting community, religious and traditional mental healthcare, and promoting self-care.8

Since 1994, new South African legislation has supported this. The National Health Act 61 of 20039 and the Mental Health Care Act 17 of 200210 re-organised the healthcare system to one based on WHO’s Primary Health Care (PHC) approach, and advocated for the integration of mental healthcare services into general health care at all levels. However, supportive legislation has not translated into greater health sector reform,3 nor has it addressed the underlying issues of stigma, discrimination, and poorly implemented rapid de-institutionalisation.7,11–13

The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023─2030 (NMHPFSP)14 calls for scaling up community services and strengthening district mental healthcare systems. Ideally, these services should be interconnected, bi-directional, and integrated into general health services at all levels, extending beyond health care into schools, workplaces, housing and social services.8

In the past, effective integration and upscaling of community-based mental health services have been severely constrained by several factors1,3 ─ specifically, human resource scarcity and the limited availability of specialist mental healthcare practitioners. The most recent national estimations show an average of 0.31 public sector psychiatrists and 0.97 psychologists per 100 000 uninsured population.1,14

The NMHPFSP advocates for a task-shifting approach, where tasks typically performed by specialists (e.g. psychiatrists or clinical psychologists) are assigned to generalists who undergo specific training and provide services under the supervision of the specialist.14 The concept of task-shifting is not new; it has been successfully implemented in both communicable and non-communicable disease settings.15 Evidence for its effectiveness in serious mental illness, however, is limited,16 and the negative perception that the language of ‘task-shifting’ triggers in both healthcare workers and the general public is being increasingly recognised.16–18 The terminology of ‘task-shifting’ may contribute to the stigmatisation of mental distress.

In recognition of these critiques, collaborative care (CC) has emerged as an alternative to task-shifting for mental healthcare service delivery in South Africa. CC interventions aim to stimulate and strengthen working relationships between primary care and specialist care, recognising that mental health is integral to all health care. All healthcare providers should be equipped and supported to provide caring and compassionate healthcare.19,20 Reilly, et al. propose a formal definition of CC with ‘Type A collaborative care’ being that which incorporates four core components: a multi-professional approach to patient care; structured, evidence-based management protocols; scheduled patient follow-ups; and enhanced inter-professional communication. Type B collaborative care incorporates some but not all of the four components.21

Collaborative care also facilitates better collaboration between healing paradigms. It allows Western mental healthcare providers (psychologists, psychiatrists, mental health nurses (on which the current health system is dependent) and alternative care providers such as African traditional healers and other faith-based healers (with whom most South African patients initially consult),22–24 to work jointly in holistic, culturally appropriate health care.17,23

Additionally, the NMHPFSP requires that outreach specialists provide input beyond clinical care and advocates for a multi-faceted approach that includes clinical supervision and teaching, as well as guidance on policy development, implementation, and clinical governance to management levels.14

Following the Life Esidemeni tragedy, the Gauteng Department of Health established a mental health technical advisory committee tasked with developing a strategy to strengthen district (community-based) mental healthcare services. Their plan advised the formation of three district-based teams: a clinical community psychiatric team, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) governance and compliance team, and a district specialist mental health team.25 While grounded in evidence and well thought through for the urban and semi-urban environment of Gauteng, the plan is unlikely to be feasible in geographically distant, resource-scarce, rural health environment such as that of the northern part of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), where a collaborative care-based, multi-faceted outreach model would be more appropriate.

This paper describes the experience of, and model used to implement, a mental health outreach service in northern KZN. It is hoped that by publishing this information, other rural mental healthcare services may be supported through the initiation of similar outreach models, thus furthering the implementation of the NMHPFSP and ultimately improving access to quality mental healthcare services in rural communities.

Case description: the northern KZN Mental Health outreach programme

Context

The northern part of KZN is predominantly rural, covering approximately 37 000 km2, with a population density of 84 people/km2. It includes the districts of King Cetshwayo, uMkhanyakude, and Zululand (Figure 1). The population of approximately 3 million people, 2.3 million of whom are uninsured,26 is served by 16 district hospitals (DHs) and three community health centres (CHCs), which provide a base for many PHC clinics. These are supported by referral regional and tertiary level services provided by Ngwelezana Hospital and Queen Nandi Mother and Child Hospital. Covering distances between district and referral hospitals can require a drive of up to five hours.

KZN has an estimated 0.12 psychiatrists and 0.61 psychologists per 100 000 population, most of whom are located further away in the larger metropolitan areas of eThekwini (Durban) and uMgungundlovu (Pietermaritzburg).1 Additionally, there is a Provincial Mental Health Directorate, with a mental health director and three deputy directors based at the Provincial Head Office; and most Health Districts have a mental health co-ordinator at their district head office, appointed to co-ordinate services within the district. Although a psychiatric unit exists at Ngwelezana Hospital, the region lacks a specialist psychiatric hospital. Mental healthcare users (MHCUs) requiring extended in-patient care are referred to Madadeni Hospital (in Amajuba District, 301km or a four-and-a-half-hour drive), or to Town Hill Hospital (in uMgungundlovu, 240km or a three-hour drive).

At DHs, mental health care is primarily provided by mental health nurses, supported by medical doctors, social workers, and, in some hospitals, occupational therapists and psychologists. Most people receiving mental health care present with serious mental illness, defined as cognitive, behavioural or emotional disorders resulting in severe functional impairment.27

MHCUs requiring admission for 72-hour observation are usually admitted into general hospital wards, with few DHs having customised separate secure areas. Three DHs have permanent clinical psychologists, with one to two community service clinical psychologists allocated within the region. Each CHC has a registered psychological counsellor. Two psychiatrists, a psychiatry registrar (from the University of KwaZulu-Natal – UKZN), and a team of variously experienced medical officers (MOs) are based at Ngwelezana Hospital, which has a 30-bed in-patient psychiatry unit and provides general out-patient services, forensic assessments, and a child and adolescent clinic. Clinical psychologists at Ngwelezana Hospital and Queen Nandi Regional Hospital provide psychological in-patient and out-patient services, as well as forensic victim and child justice assessments.

The outreach model

An adapted, multi-faceted, collaborative model guides outreach activities.17 The key elements of the outreach programme can be organised into those relating to clinical care, and those of upskilling providers and improving clinical governance.

Clinical care

While all four core components of Type A CC21 are seldom fulfilled, CC is implemented as much as possible in resource-constrained settings according to the Type A components:

-

Multi-disciplinary approach: at most sites, a professional nurse or community service MO based at the DH or CHC acts as a case manager and co-ordinates generalist primary care. Outreach specialists (psychiatrists and clinical psychologists) based at Ngwelezana Hospital and the local (DH or CHC) facility’s multi-disciplinary team members, such as social workers, occupational therapists, pharmacists and dietitians, collaborate as appropriate. The outreach psychologist at hospitals provides psychological services without a local psychologist, through regular onsite visits.

-

Structured management plan: use of the National Department of Health’s (NDoH) PHC, Paediatric and Adult Hospital-level Standard Treatment Guidelines as well as other evidence-based guidelines, including the Adult Primary Care clinical tool,29 the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme,30 and screening tools, are encouraged.

-

Scheduled follow-ups are conducted with patients and their families to monitor clinical status and provide therapeutic interventions. However, these have not been manualised and are guided by clinical judgement of need.

-

Enhanced inter-professional communication: outreach specialists aim to make themselves more collaborative than hierarchical by engaging in regular physical visits, and allowing for clinical advice and case reviews to be provided via mobile phone and messaging service platforms between visits.

Complex cases are identified and referred for review at Ngwelezana Hospital, and gate-keeping referrals to psychiatric hospitals reduce the burden of inappropriate referrals on patients and the system.

Upskilling providers and improving clinical governance

Initiatives included:

-

regular psychiatrist/psychologist outreach visits to DHs with a focus on training hospital staff, case-based teaching rounds, identifying and developing staff interested in mental health care, and supporting service development;

-

in-reach and training for DH MOs, including preparation for the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa’s Diploma in Mental Health;

-

collaborative support to the district mental healthcare co-ordinators;

-

regional training workshops for mental healthcare teams; and

-

mental health awareness and training for district managers, hospital and PHC staff, and intersectoral partners.

Funding/logistics

The outreach programme is supported by provincial, district and senior hospital management, and funded via Ngwelezana Hospital’s KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health (KZNDoH) budget. Additionally, the programme has been awarded two Institutional Awards from the Discovery Foundation, for psychiatry and psychology respectively.

Ngwelezana Hospital provides a dedicated mental healthcare vehicle for hospitals within a two-hour radius. For more distant sites, visits are supported by Red Cross Air Mercy Service, through a provincial agreement.

Application and outcomes of the model

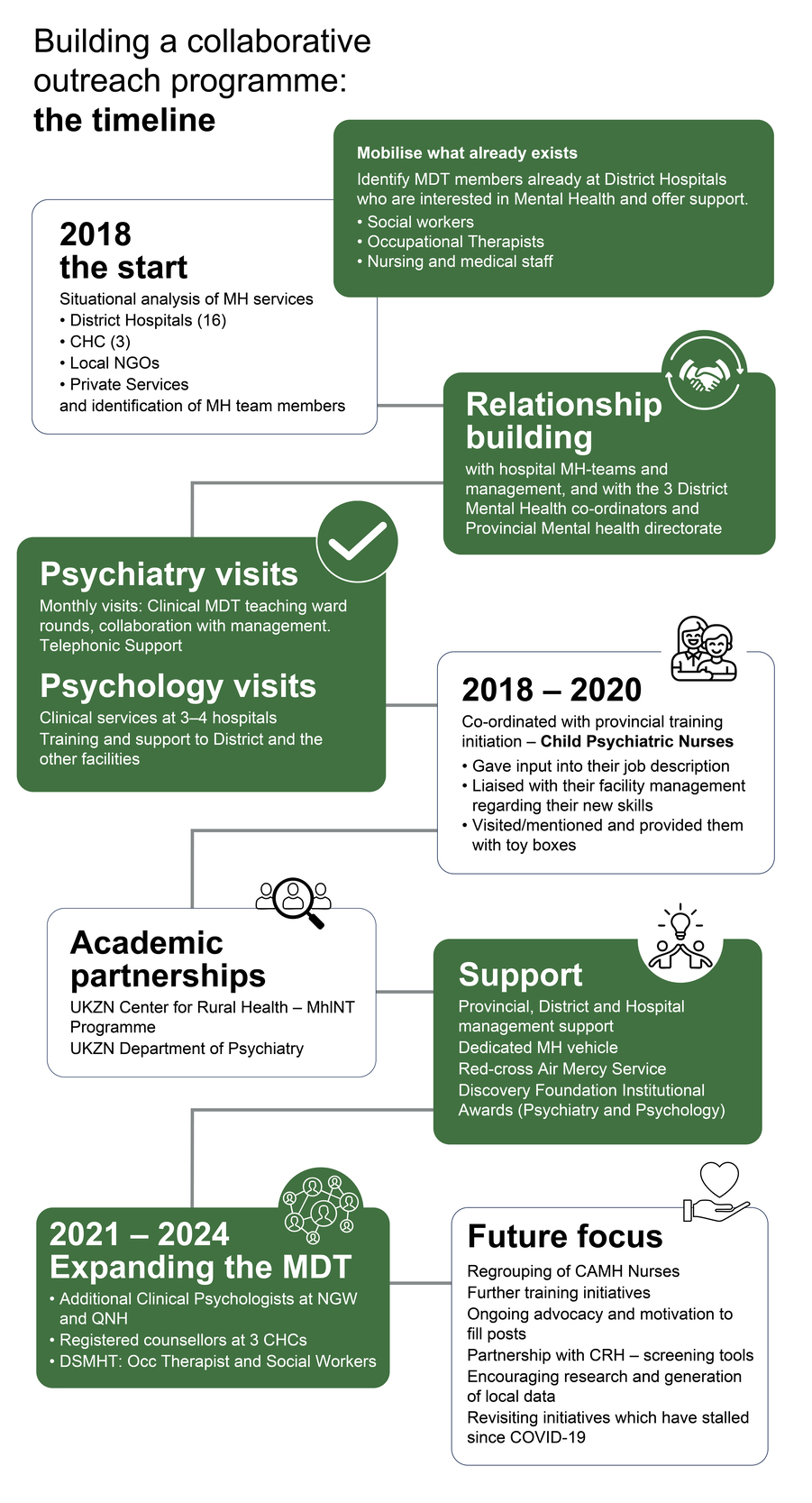

The focus has been on building a sustainable system and strengthening existing resources. This is a dynamic process, with some areas of service provision developing while others struggle. Key milestones in the process from initiation in 2018 to date are highlighted in Figure 2 and then discussed.

Situational analysis and relationship-building

In late 2018, the process began by collaboratively partnering with the three district mental healthcare co-ordinators, listening to their concerns, and identifying available resources. The Provincial Mental Health Technical Advisory Committee was reconstituted, facilitating synergy with the Provincial Mental Health Directorate. Situational analysis and relationship-building through visits and engagement with hospital staff is an ongoing process, as rural healthcare staff turnover is frequent. Relationships have also been formed with mental health NGOs, intersectoral departments, and private colleagues.

Developing child and adolescent mental health

Between 2018 and 2020, an initiative by the Provincial Mental Health Directorate sent 20 mental health nurses from the region for further training in child psychiatric nursing. Through collaborative engagement, the Psychology Department at Ngwelezana Hospital assisted in developing a job description for this group and provided support, including site visits, ongoing training, mentorship, and provision of toy boxes. An important task was engaging with nursing management regarding their new role and appropriate placement upon returning from their training. In 2019, a weekly child mental health clinic was established at Queen Nandi Regional Hospital in collaboration with the Paediatric Department. Up-referral of complex cases was to this clinic or to the weekly child and adolescent clinic at Ngwelezana Hospital. Subsequently, referral pathways have further developed to include the Psychology Department at Queen Nandi, in collaboration with Paediatrics, Social Work, and Occupational Therapy.

District hospital strategies

The initial approach was to identify multi-disciplinary team (MDT) members interested in mental health. This required flexibility, as each hospital’s staff component and organisational structure is unique. Consequently, DH MDTs could include mental health nurses, MOs, community service staff, social workers, occupational therapists, psychologists, and registered counsellors (RC).

Ngwelezana’s Psychiatry team initiated monthly outreach visits to all the DHs, with a primary focus on teaching MDT ward rounds. These visits fostered supportive relationships with key staff, and provided opportunities for presentation, discussion, and collaboration regarding psychiatric management. Further telephonic discussion of complex cases was encouraged, and the visits help staff to know who they are talking to on the phone.

The Psychology team began regular clinical service visits to four hospitals and provided support and training at district level and to the district mental healthcare co-ordinators.

Research and academic collaboration

Locally produced evidence is essential for quality care. In 2018, the outreach team partnered with the UKZN Centre for Rural Health (CRH) Mental Health Integration into Primary Care (MhINT) programme team. MhINT is an implementation research programme aimed at integrating mental health into PHC through improved detection of common mental health conditions, referral pathways, and community-based counsellors’ training on depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and non-adherence. The programme also involves the implementation of a PHC-based group intervention model with structured supervision, support, and a referral system. Following initial consultations, training and orientation, the programme was piloted at an identified DH.31

Ngwelezana Hospital is a training site for the UKZN Department of Psychiatry. Psychiatry registrars rotating through Ngwelezana participate in rural outreach, which exposes them to collaborative psychiatry and highlights the needs of patients and staff in rural DHs. This exposure is advantageous, as they are trained in systems relevant to South Africa’s healthcare needs.

COVID-19

In 2020, all outreach and training stopped due to the COVID-19 lockdown. As restrictions eased, systems had to be rebuilt, and some initiatives have yet to be restarted. However, mental health awareness has grown substantially among the wider health MDT and hospital management since the pandemic.

Human resources

Staffing at rural hospitals can be challenging, and even tertiary centres like Ngwelezana struggle with limited capacity and high staff turnover. Psychiatry has lost specialists to private practice or more urbanised centres, although MO staffing has remained reasonably stable, with turnover mainly as a result of personnel joining registrar training. Psychology capacity has increased due to pandemic-driven mental health awareness. Ngwelezana Psychology Department received additional posts, and Queen Nandi posts were unfrozen and filled, resulting in a significant reduction of out-patient waiting times at both hospitals and improved outreach capacity. Currently, two outreach psychologists per district provide clinical services at DHs with no permanent psychologist by visiting every six to eight weeks.

The wider mental health MDT

In 2022, RCs were appointed on contract at three CHCs in the region. Ngwelezana’s outreach psychologist initially co-ordinated with management regarding their role and resources, and now provides clinical support and a referral pathway for complex cases.

In 2023/24, as part of an initiative to develop district mental health specialist teams as outlined in the NMHPFSP, a social worker, occupational therapist (OT) and clinical psychologist were appointed in King Cetshwayo District. This will hopefully contribute to the greater integration and upskilling of these key groups of health professionals in the provision of mental healthcare services. The outreach team has initiated a collaborative process to support their work. The areas of focus include:

-

strengthening the OT’s rehabilitation role in mental health;

-

parenting skills training for social workers, with an initial target group being parents of adolescents who have attempted suicide;

-

motivation for the filling of mental health-related vacant posts;

-

continuity of and retention in care between hospital and community mental health services;

-

mental health awareness initiatives; and

-

intersectoral collaboration.

Training

The outreach team has focused on various forms of formal and informal training, with ongoing support and implementation being key. These include:

-

clinical training through direct patient consultations and ward rounds;

-

meetings on outreach visits with the hospital staff to address identified topics;

-

day-long workshops at district level with mental healthcare staff from all the hospitals in the district;

-

targeted training for particular groups within the mental healthcare team or wider healthcare team;

-

MOs spending time at Ngwelezana with the psychiatry team (in-reach) to upskill and complete the Diploma in Mental Health;

-

supporting MOs at Ngwelezana to up-skill in preparation towards entering specialist training;

-

encouraging and supporting staff in academic and further professional development;

-

clinical supervision and mentorship for community service psychologists and RCs; and

-

an application to train intern clinical psychologists and expose them to working within this setting.

Recognition of interests and further professional development is important for retaining staff. Areas of research and further training have included diverse but important areas: traditional medicine approaches to mental health; gender-affirming health care; palliative care; pain management; intellectual disability; child and adolescent mental health; group therapy; neuropsychology, and neurodevelopmental assessment of children with multiple disabilities.

While training has primarily focused on facility-based staff, collaborative relationships with district mental healthcare co-ordinators and UKZN MhINT teams have allowed for some integration with outreach nurses and community health workers who provide home- and community-based services.

Current focus areas

-

Regrouping of Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMH) nurses: this group, in particular, has struggled with attrition due to movement to major centres, promotion into management positions away from clinical services, retirement, and death.

-

Use of Discovery Foundation funding in further targeted training and skills development within the MH MDT.

-

Ongoing motivation and support of management for filling of psychology, OT and social worker posts at DHs.

-

Development of culturally appropriate child and adolescent mental health screening tools in collaboration with UKZN CRH.

-

Support and development of psychology and MH teams in terms of particular areas of professional interest or research.

-

Revisiting training and support of PHC staff, given that the MhINT initiative had stalled during COVID-19.

-

Research collaboration as a means of implementing and evaluating innovative approaches.

Lessons learnt

Work with what you have

The mix of mental health professionals varies widely across hospitals. Some have full MDTs, while others have limited staff. The best approach is to work with interested staff, adapt according to available resources, and focus efforts where there is traction. An example of this is the role of retired mental health nurses who work within the NGO sector, providing vital community-based follow-up and liaison with families.

Prioritise staff retention through targeted strategies

High staff turnover at district and regional hospitals is an inevitable feature of rural health care. Junior medical staff, OTs and psychologists are allocated to rural hospitals for a community service year and then move on. Nursing staff are rotated out of mental health roles or are promoted into management, away from direct mental health clinical services. Losses also occur due to death, retirement, relocation for personal reasons, or pursuit of specialist training.

Retention strategies must consider both DH staff receiving the outreach and staff providing the outreach. Effective strategies include:

-

actively identifying and supporting new staff with an interest in mental health;

-

collaborating with management to align training with mental health service needs, then providing opportunities for further professional development through online courses, conferences, and meetings; this maintains and develops skilled practitioners and provides staff with the satisfaction of their own professional development;

-

fostering research and academic links to address the isolation that can be experienced away from urban centres; and

-

investing in capacity-building to strengthen the system as a whole.

Identify mental health champions

A key element has been the identification of mental health champions, who have variously been MOs with an interest in mental health, mental health professional nurses, social workers, RCs, OTs, or a combination of these. A single individual in a DH who knows the patients with mental illness and acts as a local ‘specialist’ can make a huge difference, with the longer-term goal of building and valuing the MDT.

Supervision must be collaborative, informed and accessible

Community workers cannot be expected to provide emotional support to families and individuals in often complex emotional situations without strong support, clear boundaries, and defined referral pathways.

The expectation that certain mental health roles can be task-shifted to other health professionals does not remove but in fact increases the need for ongoing supervision and support. Effective, informed supervision relies on collaborative relationships, with the freedom and accessibility to ask the necessary questions. Ongoing support and training are key. Collaborative care models provide a pragmatic strategy to integrate mental health care into PHC.10

Lack of supervision has also been shown to contribute to burn-out and staff attrition in rural hospitals.32 In addition to clinical supervision, staff mentorship, psycho-education on self-care, and a staff psychology clinic should be provided.

The in-person visits are important

While it is possible to consult remotely, in-person visits are essential for building relationships with the DH staff and management, facilitating on-site teaching, and seeing patients directly. Sometimes, the patients who are not referred have the greatest need for specialist input.

Technology has its limitations

Digital platforms such as VULA and WhatsApp have significantly improved access to specialist advice. However, psychiatric patients are complex, and a telephonic consultation is often needed. Limited network connectivity in rural areas hinders the wide-scale implementation of tele-psychiatry platforms. The reality of rural situations is that even telephonic contact can be unreliable.

Promote consistent use of evidence-based tools and guidelines

Standard treatment guidelines are essential in improving the quality of care. The NDoH Standard Treatment Guidelines33 are a valuable resource readily available on the EM Guidance App.34 DH staff need regular reminders about these guidelines. Validated screening tools help in identifying substance use disorders, Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and behavioural difficulties in children. Useful open-access assessment tools for patient evaluation include the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; the SNAP IV for evaluating ADHD; a battery of open-access neuropsychological assessment tools; and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Proprietary psychological assessment tools require proper asset management control.

Modest infrastructure upgrades could facilitate better service delivery

A significant proportion of urgent consultations require advice regarding the management of severely behaviourally disturbed patients, and most DHs lack adequate infrastructure to manage these patients safely. Confidential counselling space is also limited. Modest and cost-effective infrastructure upgrades should be prioritised to fulfil these growing service delivery needs.

Robust, bi-directional referral pathways are required

Reliable referral pathways are crucial for empowering and reassuring DH staff who manage complex cases. Regional referral pathways are complicated by insufficient psychiatric beds; skewed MH staffing, with more staff at regional/specialist level than at community level; no specialist psychiatric hospital, and long geographical distances, meaning that patients are often treated far from home. Simply shifting staff and resources to the community level risks a system-wide collapse; rather, system-wide capacity must be built, with mental health being integrated into PHC services, and a robust, bi-directional referral pathway being developed.

Dedicated transport helps efficiency

Distances between district and regional hospitals are long, and for some rural hospitals, driving out and back in a day is not possible. The Red Cross Air Mercy Service has provided flights to various landing strips, from which DHs can collect visiting outreach staff, ensuring a vital service by reducing travel times and enabling specialists to have more ‘time on the ground’ during their outreach visits. Having a dedicated mental health vehicle has enabled more consistency in accessing transport for more local outreach visits.

Specialist outreach adds strategic and governance value.

Specialist outreach adds value beyond clinical consultation and teaching; it must also support clinical governance at DH with patient safety incidents, staff deployment, medico-legal and forensic matters, and assessment of impaired staff.

Intersectoral collaboration is a cornerstone

Given the complex nature of mental health, collaboration with the Departments of Education, Social Development, Justice, the police service and the NGO sector is essential. Building these constructive, working relationships is an ongoing process.

Movement is not always forward

There are instances where processes start and stop. Negative impacts on the programme have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, key staff leaving, plans falling apart, road closures, vehicle hijackings, and cancelled training. Additionally, staff are sometimes resistant to taking on mental health roles, and new staff are dropped into situations with limited support or direction. It is helpful to take time to reflect, re-evaluate, and collaboratively plan a way forward again.

Conclusion

Providing quality rural district mental health services presents a particular challenge to health departments due to long distances, limited staffing and infrastructure, and high turnover rates among medical staff. A collaborative care model provides a useful framework for developing and improving service provision. Building relationships between specialist mental health staff and district-level staff is critical. Task-shifting should not be seen as a substitute for the provision of adequate numbers of mental health service providers. District mental healthcare teams should be expanded beyond the current sites, and attention should be paid to providing mental health-trained staff at the sub-district and district hospital levels. In particular, the provision of RCs and clinical psychologists, and mental health OTs in every sub-district should be prioritised. Data collection at DH level should be improved to include outcome measures such as average length of stay, re-admission rates, and retention in care.