Introduction

The Western Cape Department of Health and Wellness (WCDoHW) envisages a health system by 2030 that brings care closer to the community, promoting well-being.1 The WCDoHW Health Care 2030 plan (HC2030) advocates for comprehensive, quality care packages that cater for all health needs across the life course, are accessible, and enhance the quality of life of beneficiaries.1 Despite prioritising mental health services in the province, the implementation of comprehensive mental healthcare packages inclusive of community-based psychosocial rehabilitation remains a challenge for service managers, policy-makers and clinicians. The ongoing acute mental health facility pressures, practice in silos, bio-medical focus, poor access to out-patient services, stigma attached to mental health illnesses, and human resource constraints result in mental health care service gaps.2 These and other challenges lead to ‘revolving door’ patients, poor adherence to treatment, inappropriate use of acute services, and premature discharges.

The mental healthcare gap in the Western Cape prevails throughout South Africa.3 Recognising the impact of mental, neurological and substance use (MNS) disorders on the healthcare of the nation and the shortage of specialist mental healthcare providers, the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf/the Academy)3 presents a vision for existing healthcare personnel to function in a task-sharing/task-shifting system. Task-sharing and task-shifting involves the rational distribution of tasks among health workforce teams, with mental health care provided by non-specialists under the training, supervision and support of specialist mental health workers.4 Task-sharing emphasises collaboration and support between specialists and non-specialists to improve access to mental health care.

Task-shifting typically involves transferring tasks from highly specialised health professionals to less specialised staff, often due to a shortage of specialists.5 The Academy proposes the integration of mental health into general health care, particularly the capacitation of community health workers (CHWs) in basic psychosocial rehabilitation and disability-inclusive community development skills.3

Similar recommendations for investments towards rehabilitation in a community-based health system were outlined in a report by Thematic Commission Pillar Five of the Presidential Health Summit.6 The Pillar Five report proposes a shift in focus from curative to promotive and preventive health care, and increased appointment of CHWs. It recognises the need to formalise the training and scope of practice of CHWs, including their competencies and roles in delivering rehabilitative services. A conceptual re-alignment by health system managers and human resource planners would be necessary for these recommendations regarding rehabilitation in community-based services (CBS) to materialise.6–8

The WCDoHW project described in this paper exemplifies the implementation of these human resource strategies, and is based on the Community-orientated Primary Care (COPC) practices implemented by a rehabilitation team in the Klipfontein/Mitchells Plain sub-structure (KMPSS) in the Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality. It details some of the management decisions taken to implement the WCDoHW HC20301 aspirations at local level, with particular focus on the leadership strategies that led to the improved and impactful implementation of rehabilitation services throughout the continuum of mental health care.

This paper foregrounds the strategic human resource management approaches used to develop and utilise a cadre of rehabilitation care workers (RCWs) as members of COPC rehabilitation teams. COPC is a “continuous process by which primary health care (PHC) is provided to a defined community on the basis of its assessed health needs by the planned integration of primary care practice and public health”.9(p3) The COPC process aligns public health services for the burden of disease in a geographically defined community with PHC through health promotion, disease prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care delivered by teams of CHWs that are supported by nurses and sometimes by doctors based at a PHC facility.9

The authors focus on the role of RCWs who are supported by rehabilitation therapists to provide basic community mental health and other disability-related services. RCWs have formal entry-level certification in disability inclusion and rehabilitation care work. Many of the RCWs employed in the KMPSS are CHWs with this certification.

Case description

Piloting rehabilitation care workers

The development of a mid-level rehabilitation health workforce for HC2030 began in 2012 with a pilot project undertaken by the WCDoHW and the University of Cape Town (UCT) in collaboration with the University of the Western Cape and the University of Stellenbosch. The pilot aimed to design a curriculum in disability management and community-based rehabilitation, and to train an initial cohort of 33 CHWs to become certified RCWs. Students in the first cohort were either employed by or volunteering at non-profit organisations (NPOs). The one-year, full-time curriculum for a Higher Certificate in Disability Practice (HCDP) was hosted by the Division of Disability Studies at UCT. The first cohort of 28 students graduated in 2014. UCT remains the training institution for this certificate course. The outcome of the pilot project was a new cadre of mid-level health worker in the WCDoHW called a rehabilitation care worker. The RCWs extended the rehabilitation service in the CBS where they were employed, including a facility-based, six-week in-patient transitional care service that is outsourced by the WCDoHW to NPOs. Since the project’s inception, 121 RCWs have graduated to date (2024), most of whom are employed in government posts or by NPOs funded by government.

Reflections on the 2014 outcomes led to a second pilot project incorporating speech, language, swallowing and audiology services into the HCDP curriculum and into PHC and CBS platforms. In 2017, the KMPSS, along with other sub-structures in the Cape Town Metropole, piloted a COPC approach in one geographic area per sub-structure, to test its feasibility and benefits.9 These projects afforded the authors an opportunity to collaborate with RCWs through task-sharing and task-shifting. Practice-based evidence in the pilot sites has highlighted the RCWs’ contribution to enhancing people’s access to basic disability-inclusive and rehabilitative services closer to where they reside.

In 2019, the KMPSS management faced pressure to incorporate mental health services into the PHC and CBS platforms. Improved access to primary-level mental health services was needed to relieve the high demand at the acute service level at Mitchells Plain Hospital and Lentegeur Hospital, the latter being a mental health specialist hospital. A continuum of mental health care was urgently required. The KMPSS rehabilitation team, including RCWs, embraced the opportunity to expand their role in CBS and COPC to include psychosocial interventions in anticipation of hopeful outcomes based on the three approaches that are described in the next section.

Method

In assessing the outcomes of this intervention, the authors employed a qualitative, reflexive methodology. Reflexivity as a research approach is “an intentional intellectual activity in which individuals explore or examine a situation, an issue, or object based on their past experiences, to develop new understandings that will ultimately influence their actions or in which they critically analyse the field of action as a whole”.10(p539) Structured group dialogues were used to critically reflect on and analyse professional experiences and make recommendations for further actions.10 Through the reflexive process, insights were collectively articulated around three themes: the implementation of the HCDP programme, role distinctions between RCWs and rehabilitation therapists, and strategic leadership in policy translation.

The HCDP programme

Re-engineering PHC in South Africa requires building human resource capacity, particularly in the field of rehabilitation and disability, which is under-resourced and does not meet the needs of persons with disability across the lifespan and their families.8,11 The human resource plan of the National Department of Health (NDoH) advocates for CHWs as part of the Ward-based Primary Health Care Outreach Teams (WBPHCOTs) to address, among other healthcare programmes, the rehabilitation needs in communities.12 However, CHWs are not capacitated to deliver the basic disability-inclusive and rehabilitative interventions needed for non-communicable diseases and MNS disorders that are prevalent in a population across the lifespan.3 CHWs require formal certification in basic disability and rehabilitation competencies, and should be supervised by rehabilitation therapists.3

The HCDP programme, accredited at National Qualification Framework Level 5, is the first formal higher education initiative for mid-level health workers in the Western Cape. It provides opportunities to upgrade the informal certification skills of CHWs by taking into consideration recognition of prior learning and work experience. The programme also caters for Grade 12 graduates. The qualification develops foundational skills for health promotion, disability prevention and care, basic rehabilitation, and family support. The RCW skills set serves as a bridge between multi-sectoral public sector services, non-government organisations (NGOs) and NPOs, particularly with regard to early childhood development, schooling, and access to work and leisure opportunities.

The RCW’s primary tasks are to screen for persons with impairments, assist them with participation in everyday activities such as self-care, learning, work, and play, and to promote their social inclusion. Using the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health13 as a conceptual framework, the HCDP curriculum includes the impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions associated with the most prevalent MNS disorders. The RCWs advocate for access to services and resources using elements from different components of the WHO’s Community-based Rehabilitation (CBR) Guidelines,14 including the CBR mental health guidelines.

RCWs perform their roles in people’s homes and other community spaces. Clinical guidance and governance of the RCW scope of practice must, however, be provided by the relevant rehabilitation therapists in the district where they are employed. The professionals who are eligible to provide the necessary clinical supervision are either occupational therapists (OTs), physiotherapists (PTs), speech and language therapists (SLTs), or audiologists. OTs provide supervision of RCWs working with mental health clients.

The HCDP programme consists of four theoretical courses: inclusive development and agency; disability information, management, and communication systems; promoting health and well-being; and health and functional abilities, along with one work-integrated practice learning course. The programme aligns with the National Skills Development Strategy aiming to promote a skills system that responds to labour market needs and promotes social equity.15 The work-integrated course addresses social equity by ensuring that RCWs are adequately prepared to provide essential services to people with disabilities and are equipped to enter the workforce.

Role distinction between RCWs and rehabilitation therapists

Rehabilitation care workers play a vital role in the recovery of persons with mental illness, however, they cannot function independently, which foregrounds the role of the supervising rehabilitation therapist. The ASSAf report3 on provider competencies for MNS disorders indicates that ideally, CHWs with RCW certification should be supervised by rehabilitation therapists such as OTs and clinical social workers, and that the current curricula for nurses, doctors, psychologists and other key providers do not yet adequately prepare them to deliver comprehensive rehabilitation and community-based disability-inclusive development services. Rehabilitation therapists are positioned to supervise RCWs in meeting the needs of persons with physical, sensory and psychosocial impairments. However, in the PHC setting, roles have become blurred as duties among healthcare professionals are shared and duplicated to ensure that communities are optimally serviced and treatment gaps are prevented. Therefore, it is important to establish guidelines, roles and responsibilities to ensure accountability and successful service provision. Table 1 outlines some core functions of the RCW and the supervising rehabilitation therapist.

Table 1 depicts the collaborative partnership between the therapist and the RCW, indicating that the RCW cannot function independently within the CBS context. The supervising therapist provides the overall case management, referring to the co-ordination and oversight of mental health services, ensuring that the client’s needs are met through appropriate services and interventions. Mental health intervention activities, psychosocial disability prevention, and mental health promotion group activities provided by the RCWs at community-based venues require regular supervision and team meetings. Understanding the roles of each service provider and facilitating these responsibilities leads to optimum impact and beneficial effect within the CBS rehabilitation service. It is the therapist’s role to contain and guide RCW activities with the individual(s) concerned, whether in the home, group or community setting. A synergy of collaboration, sharing, and engaging practice requires nurturing as the RCW becomes the extension of the rehabilitation team in the community. Mental health services require careful task-shifting and sharing between the RCW and therapist, especially in PHC contexts at the primary and CBS levels, where the emotional toll of mental health care can lead to provider burn-out and compassion fatigue. The therapist plays a continuous role in guiding and developing the RCW’s skills, while also addressing the impact of social determinants of health on the RCW’s productivity and mental well-being.

The CBS rehabilitation team, consisting of rehabilitation therapists and RCWs, collaborates with other professionals such as social workers and registered counsellors, as well as with relevant stakeholders in government sectors and NGOs to achieve community-wide outcomes. The WCDoHW funds one specific NPO per PHC facility in the Cape Town Metropole to provide integrated CBS, including treatment interventions, disease prevention, health promotion, and palliative care. These NPO teams, which include nurses and CHWs, collaborate with rehabilitation teams to enhance disability inclusion and rehabilitation. Although such collaboration currently occurs infrequently, the goal is to strengthen the partnership between the WCDoHW, NPOs and communities to optimise the continuum of care.

Strategic leadership and policy translation

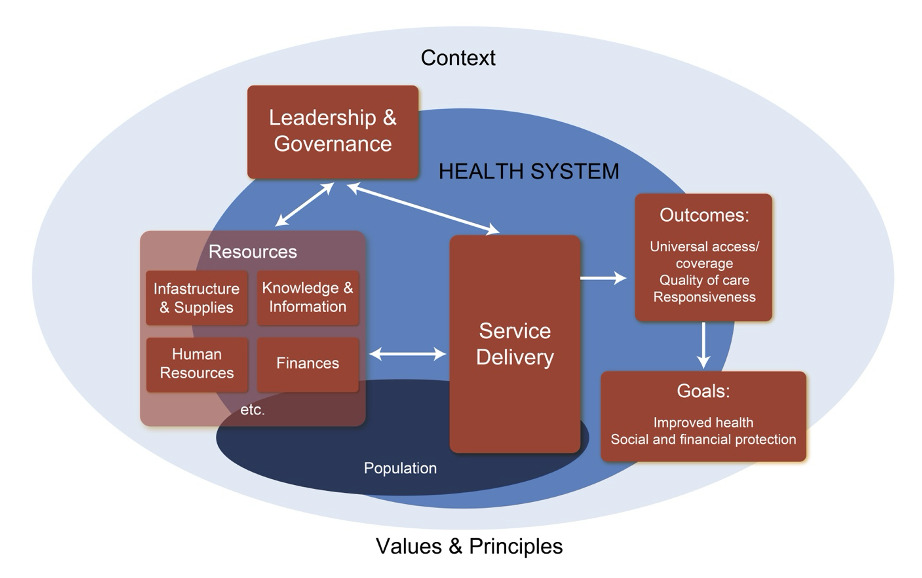

The KMPSS CBS rehabilitation model offers valuable insights for further reinforcement and replication in other settings. Each pilot project provided practice-based evidence for reconfiguring services to address unmet disability-related health needs. Small feasible structural changes applied in the broader context after the pilot projects resulted in significant service improvements. Health managers, recognising the success of the projects, took bold steps to apply the knowledge, lessons and good practices more broadly in the sub-structure. However, despite the success of small studies, there is often hesitation among managers and frontline staff to scale practices due to the bureaucratic nature of government departments and the challenges of implementing changes in large, complex health systems. Nevertheless, the KMPSS model demonstrates that change is possible. Figure 1 illustrates how a systems approach to service design was used to integrate RCWs into CBS.

The context of good practice described in Figure 1 pertains to the health system in KMPSS. KMPSS is located on the Cape Flats with an estimated combined population of just over one million people. An estimated 92% of this population are dependent on public services. The foremost approach of KMPSS leadership and governance was to respond to the disability-related service needs of their population by embracing the opportunity of introducing RCWs onto the platform. This approach required engaging the local corporate management teams to support the health managers in obtaining the necessary resources to recruit, train, and pay RCWs.

In a system, the various decisions made by service managers has an influence on other parts of the system. Undoubtedly, it was clear that the service delivery of RCWs would be beneficial; however, an adequate number of therapists was required to provide clinical governance at the CBS level. Historically, all rehabilitation therapists were based at the PHC facilities. They did not go into the community, nor did they provide any CBR service. Their clients were expected ─ based on ambulatory primary level medical services ─ to attend individual, (on average) monthly rehabilitation appointments at PHC clinics. Therefore, the leaders in the KMPSS had to consult with the rehabilitation therapists to motivate them to work in the community, i.e. to be willing to apply their disability-inclusive development and CBR competencies. These negotiations required a range of human resource management interventions such as knowledge- and information-sharing, change-management strategies, and additional training for therapists on their CBS rehabilitation role expectations. Importantly, a series of facilitated support workshops16 were offered at which therapists and RCWs could process their mutual expectations, concerns, and shared values and service principles.

This process of role-transitioning triggered a new way of working among the rehabilitation therapists. For example, OTs became ‘community-rich’ service providers and the main clinical governance support to the RCWs. Physiotherapists and audiologists became the ‘facility-rich’ service providers, and the speech language therapists started working in both the community and the facility depending on need. The OTs provide limited facility-based services, and the PTs provide limited CBS, depending on the health needs of the population they serve. The goals and outcomes of CBS rehabilitation were promoted by enabling flexible re-allocation of roles evidenced by increased referrals, compliments from service users, and endorsements from referring facilities. Due to the positive feedback received, the broader KMPSS management team supported the conversion of posts from other professional groups and prioritised additional funding to appoint more OTs. The KMPSS managers provided strategic support through hosting consultative workshops and ongoing feedback loops with the affected staff, referring facilities, and patients. They were positioned to design continuum models of care and a robust referral system for a CBS rehabilitation service that included mental health. Local management policies were then designed to provide direction and support. However, the service provision was handed to the therapists to take the lead, with fruitful outcomes for the people served and for the local CBS health system.

In summary, firm intentional leadership led to strategic policy decisions by management at local level in deliberations about the resources required for CBR service delivery, which paved the way for more optimal health outcomes that overtly situated rehabilitation as an integral part of universal health coverage. In particular, the principles of CBR and the values of disability-inclusive development informed the original decision of the KMPSS management team to take the bold step of piloting the RCW pilot project in 2012.

Key outcomes

Case-based evidence

The impact of the approaches described above is illustrated in Box 1 by the anonymised case of RK, a 31-year-old female referred to CBS rehabilitation in July 2022 after being discharged from Mitchells Plain Hospital for a major depressive episode.

Expanding access to rehabilitation

There are currently 11 OTs (four in 2013) and 32 RCWs (six in 2014) working in two CBS rehabilitation teams in the KMPSS. Since 2019, the referral of mental healthcare users and the provision of a CBS recovery-orientated mental health and family support programme have steadily increased. The rehabilitation team has incorporated mental health care for all of their clients across the lifespan, irrespective of presenting impairments. Thus, a client referred for stroke rehabilitation, where only the ‘physical’ aspects were addressed, will now also receive intervention for signs of depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns. Statistics for the CBS rehabilitation services for mental healthcare users since 2019 indicate a collective caseload of eight to 10 individuals and their family at any one time. Statistics also indicate that since the start of 2024, there has been an increase to a collective caseload of 50 to 55 clients at any one time. These statistics suggest that as the population and disease profile have changed, so too has the need for an integrated CBS workforce inclusive of psychosocial disability and recovery-orientated rehabilitation.

The contribution of a disability-inclusive and rehabilitation-capacitated workforce to strengthen the primary mental healthcare system warrants policy attention. Firstly, CBS rehabilitation not only benefits persons with disabling MNS disorders and their families, but also the communities in which they live. Secondly, CBS rehabilitation is also a component of universal health coverage and an important goal of the envisaged National Health Insurance.17,18 Although the Presidential Health Summit6 listed rehabilitation as a component of comprehensive health care, there is currently no framework for the inclusion of rehabilitation in COPC. The KPMSS perspective could serve as an exemplar towards good practice in other health system sub-structures. Thirdly, the workforce planning for rehabilitation at primary level is hampered by outdated knowledge on CBR and limited understanding of disability-inclusive development among health-system planners, government officials, and healthcare workers.8

It is acknowledged that rehabilitation therapists and RCWs are scarce human resources for universal health coverage. Task-shifting and task-sharing competencies enable the reach of scarce rehabilitation therapists to be extended through partnerships with RCWs. The range of responsive approaches used by RCWs, combined with their deep familiarity of community dynamics and networks, would make their role invaluable ─ particularly in under-served areas, including rural areas.

Lastly, the KMPSS CBS rehabilitation model of care has facilitated opportunities to engage in activities linked to the wellness approach with disease prevention and health promotion strategies being prioritised. For example, clients are supported with ‘return to work’ interventions; parents are supported with ideas for home-based play and development stimulation; youth with challenging behaviours are linked to group-based peer support services; and isolated elders are assisted to connect with relevant community organisations.

In accordance with the intersectoral principles of CBR,14 the CBS rehabilitation team, and specifically the RCWs, work collaboratively with other government sector representatives. They are positioned to act as linking agents for promoting the personal recovery, social inclusion, and participation of persons with mental health disorders. The emphasis of this exemplar of good practice is on the importance of being person-centred and prioritising the inclusion of all persons within a community through collaboration with various stakeholders and participation in intersectoral collaboration for better health outcomes and good quality of life.

Discussion

Public health workers, including RCWs and CHWs, typically work from 08h00 to 16h00, Monday to Friday, which limits their ability to support employed clients. For instance, when RK returned to work, she could not meet with RCWs during the day. Similarly, RCWs and CHWs cannot provide family support when no-one is at home. Flexible working hours for RCWs and CHWs could be explored to accommodate such clients, but this would have to be in consultation with all stakeholders and be consistent across the team, including supervising therapists.

The current system for capturing rehabilitation service statistics is narrow, only tracking the number of assistive devices issued at PHC clinics. CBS rehabilitation services, including mental health recovery interventions, are not captured, and data are informally gathered by therapists for reporting on the National Framework for Disability and Rehabilitation descriptors for CBR.19

RCWs are employed by NPOs funded by the WCDoHW and contractually managed by those NPOs, while clinical governance is shared with WCDoHW rehabilitation therapists. This arrangement relies heavily on strong working relationships between the NPOs, departmental officials, and therapists. More integration of mid-level health worker positions into the public sector health system is needed.18 The KMPSS team faced challenges in introducing RCWs as mid-level workers, requiring regular role-clarification between rehabilitation therapists, RCWs, and CHWs. Strengthening the alignment of RCWs’ and CHWs’ roles is a priority for health and rehabilitation managers.

Another limitation highlighted in this study is the gap in curricula for healthcare professionals, such as nurses and doctors, in rehabilitation and disability-inclusive development. This gap may contribute to a lack of interdisciplinary collaboration and hinder the integration of disability studies and rehabilitation services into comprehensive healthcare delivery.

Recommendations

It is recommended that professional boards, training institutions, and employers consider upskilling RCWs through career-laddering to a higher certification level. An additional year of training to become a community rehabilitation worker with a broader intersectoral scope would provide a career development pathway. Two RCWs have successfully entered the occupational therapy programme at a local university through recognition of prior learning, although this required that they resign from their roles and secure their own funding.

The KMPSS experience highlights that CBR is crucial to comprehensive care, and RCWs and rehabilitation therapists should be integrated into WBPHCOTs, alongside nurses and CHWs, as outlined in current policy. In line with this recommendation, we must explore and formalise task-sharing and task-shifting between RCWs and CHWs, particularly in areas such as supporting daily living independence and screening for functional deterioration as part of this collaborative, inter-disciplinary care model.

Additionally, this paper highlights the need for future research, particularly in exploring opportunities for practitioners to share ‘lived experiences’ on under-researched topics. Another key area for exploration could be to focus on understanding the barriers and enablers to scaling small-scale successful practices within large, complex health systems, especially in the context of bureaucracy. For example, research could focus on how corporate governance could support a flexible, adaptable health service that responds to evolving population health needs and hurdles, and the cost-saving benefits of CBR.18

Finally, training institutions should incorporate disability studies, rehabilitation practices, and human rights frameworks into the curricula for all healthcare professionals, tailored to their specific roles. Additionally, inter-disciplinary training that fosters collaboration across healthcare professions should be prioritised to ensure the delivery of comprehensive, person-centred care.

Conclusion

This paper underscores the pivotal role of RCWs in advancing universal health coverage and emphasises the critical importance of bold, responsive leadership in driving local-level policy innovation. The KMPSS experience exemplifies how decentralised decision-making and adaptive management can effectively transition rehabilitation services from facility-based models to community-orientated care.

Operating within the bounds of delegated authority and resource constraints, the KMPSS team strategically responded to unmet health needs by designing and implementing contextually relevant interventions informed by practice-based evidence and pilot studies. Incremental yet deliberate changes were introduced and adopted, even when these involved unfamiliar or unconventional approaches.

A particularly noteworthy example of this leadership was the decision to support the HCDP as a foundational platform for capacitating RCWs. This commitment laid the groundwork for a more inclusive, community-based rehabilitation service model, aligned with the principles of equity, responsiveness, and sustainability.

The success of this initiative affirms the value of courageous, evidence-informed decision-making and offers a replicable model for strengthening human resources for health in support of disability inclusion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the management and rehabilitation team of the Klipfontein/Mitchells Plain substructure, and extend our deepest gratitude to Professor Maddie Duncan (Occupational Therapy Department, UCT) for her unwavering support, guidance, and encouragement.