Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health is commonly described in individual terms, i.e. the pathology of an individual who is depressed or anxious. Of course, there are individual, genetic and biological factors at play, but the mental health of children and adolescents is deeply rooted in the environments in which they live. In South Africa, those environments are commonly characterised by poverty, violence and discrimination. These threats have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate breakdown, and it is therefore not surprising that feelings of fear, anxiety and hopelessness are increasing among young people.

Mental health problems are often considered in binary terms, as if there is some clear point at which a person moves from being well to unwell. Concepts such as mental health, mental well-being, mental illness, or mental disorders are often used interchangeably. Mental health is frequently used as a way of referring to disorder or distress, but should instead be thought about as falling on a continuum. At the one end of the continuum are children and adolescents who could be described as ‘flourishing’. They are content, able to self-regulate and sustain meaningful relationships, act with agency, be productive, and manage adversity. Moving along the continuum, young people may still be managing everyday routines but experiencing anxiety and worries in one or more life areas; further along, they may be actively struggling with home, school or relationships, and display some mental distress, but not all of them have a mental disorder. It is here that early intervention and support may be essential to assist them in not progressing further to an actual diagnosis of a mental illness or mental disorder. Mental illness also lies on a continuum, from a mild time-limited illness through to a persistent disabling condition or psychosocial disability which requires concerted psychosocial rehabilitation, with family, school and community support.

This paper explores the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders, the key role of social determinants in the aetiology of well-being and mental disorders, how a life-course perspective strengthens understanding of the cumulative interplay of risk and protective factors over time, and the need to adopt a twin-track approach to address the intersections between disability and mental health.

The role of schools and health facilities are considered as two essential platforms for supporting children and families, given their broad reach, existing mandates for mental health service delivery, and their central positioning in the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023─2030 (NMHPFSP).1 The case is made that supporting child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) is not only a wise investment in children, but is also perhaps the best investment that can be made in inter-generational health, in order to break the cycle of violence, poverty, discrimination, and mental ill-health in South Africa.

The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023–2030

The NMHPFSP1 aims to strengthen mental health care through integrated, person-centred, and rights-based services. Its key priorities include integrating mental health into Primary Health Care, enhancing specialist services, and prioritising child and adolescent mental health. The framework emphasises building a skilled workforce through training and task-sharing, improving intersectoral collaboration, and promoting community-based care. It also focuses on governance, financing, and robust monitoring and evaluation to support implementation. Overall, it seeks to address mental health service gaps and ensure accessible, quality care for all, especially for vulnerable populations. This paper considers how to strengthen implementation in order to enhance outcomes for children and adolescents.

Understanding the epidemiology of CAMH

Many mental health problems have their onset during childhood and adolescence, providing important opportunities for early identification and intervention.

Early onset

A recent large-scale meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (n = 192) concluded that of those individuals with mental disorders, one third (34.6%) experience onset before the age of 14, and nearly half (48.4%) before the age of 18.2 The peak age of onset for mental disorders is 14.5 years, and the disorders most likely to emerge before 18 years of age are: neurodevelopmental disorders, anxiety/fear-related disorders, obsessive-compulsive/related disorders, problems with feeding/eating, stress- and trauma-related disorders, and depressive disorders.2

Prevalence

Reliable data on the prevalence of mental health problems among children in South Africa are scant, but globally, it is estimated that as many as 20% of children younger than 18 have a mental disorder.3 In 2006, experts estimated that the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in South Africa was 17%,4 but this number is likely to have increased since then. In one study of first-year university students in South Africa, 38.5% of respondents reported at least one lifetime common mental disorder, while the median age of onset for any disorder was 15 years (IQR = 13–17), with major depressive episodes having the lowest median age of onset (15 years).5 The most representative recent data on mental health of children and adolescents come from the Third National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey conducted in 2011, which found that nationally, 24.7% (23.2–26.2) of learners had felt so sad or hopeless during the preceding six months that they stopped doing certain usual activities for two or more weeks in a row.6

Environmental stressors

It is unsurprising that so many young people in South Africa have mental health problems, given the high exposure to risk factors such as violence and adverse childhood events. For example, one survey of 617 adolescents aged 12–15 years, sampled across multiple sites in Cape Town, found that almost all participants (98.9%) had witnessed community violence, 40.1% had been directly threatened or assaulted in the community, 76.9% had witnessed domestic violence, 58.6% had been directly victimised at home, 75.8% reported direct or indirect exposure to school violence, and 8% reported that they had been sexually abused.7

Furthermore, many children live in poverty8 with marked rates of food insecurity,9 both of which significantly compromise youth mental well-being. In addition, bullying and problematic Internet use are emerging risk factors for poor mental health among young people. Both have been linked to higher rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation, particularly in adolescence.10,11

Disability

Environmental stressors experienced by children with disabilities may place them at higher risk for mental health problems. A recent report12 raised previous estimates for children with any form of disability to one in 10 children, with psychosocial issues being prevalent across age groups. Mental disorders are a leading cause of years lived with disability, with approximately 8% of the world’s young children (aged 5–9 years) and 14% of the world’s adolescents (aged 10–19 years) estimated to live with a mental disorder.13 South African prevalence data on disability, probably under-reported at 7.5% of the population older than five years, sets decreasing prevalence rates for children, from 10.8% of 5–9-year-olds, to 4.1% of 10–14-year-olds, and 2.6% of 15–19-year-olds.14

Access to treatment

Crucially, treatment rates for mental health conditions are low, with a lack of trained health personnel and accessible and affordable child and adolescent psychiatric services. For example, only one in 10 children with a diagnosable and treatable mental disorder are able to access treatment. A pressing challenge for the implementation of the NMHPFSP is to find cost-effective ways to scale-up access to evidence-based treatments and to plan appropriate services, which is difficult in the absence of reliable nationally representative epidemiological data on child and mental healthcare needs.

Potential of a national prevalence study

Reliable epidemiological data about the mental health of children and adolescents are needed to plan effective services, set priorities, and establish prevention programmes. Existing studies typically focus narrowly on symptoms of depression and anxiety, use small non-representative samples, are observational, and/or use poorly validated assessment instruments. Diagnosing mental disorders in children and adolescents is complex, and care should be taken to use properly validated instruments to obtain accurate and meaningful prevalence estimates. Furthermore, most South African studies of mental disorders among children and adolescents to date have used only screening instruments, which typically lack specificity and sensitivity and thus identify a high number of false positives for the most common disorders, while simultaneously neglecting other less common, and potentially more serious, conditions. Indeed, the absence of well-validated screening instruments available in different languages to determine whether someone is likely to meet diagnostic criteria is an impediment to mental health research in South Africa, not only among children. There is an urgent need for a scientifically rigorous national CAMH survey in South Africa to help establish priorities, plan services, and allocate resources efficiently. The importance of such a survey was evident in a South African Human Rights Commission Report15 which explicitly called for the National Department of Health (NDoH) to conduct this crucial assessment. Plans are currently afoot to conduct a national representative survey to estimate the prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric conditions. A key deliverable for the NMHPFSP would be to advocate for and support the allocation of resources to collect the data needed for such a survey.

Addressing the social determinants

Social determinants of child and adolescent mental health refer to the social and economic conditions that have a direct influence on the prevalence and severity of mental health conditions across the life-course.16 Social determinants like poverty, violence, food insecurity, extreme weather events due to climate change, and neighbourhood safety and infrastructure all play a profound role in shaping the mental health of children and their subsequent health and well-being in later life.

Influence

There is growing epidemiological evidence of the social determinants that influence the mental health of children and adolescents in South Africa, and other low- and middle-income countries. These determinants can be organised into five main domains, those being the demographic, economic, neighbourhood, environmental events, and social/cultural domains. Each domain exerts its influence on the mental health of children and their subsequent life-course, through a combination of distal and proximal determinants. For example, the effect of economic recessions has an influence on mental health through its impact on youth unemployment, which has been shown to be associated with increased prevalence of depression in South Africa.17 These domains often interact, creating more severe adversity for children who experience an intersection of social determinants. For example, children exposed to violence in the context of food insecurity are at particularly high risk. Each of these domains show strong alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), offering some key opportunities for policy interventions.16

Interventions

Several potential targets have been identified to address the social determinants of the mental health of young people18 which can be incorporated as interventions included in the implementation plan of the NMHPFSP.

-

In the demographic domain, these include school-based mental health promotion and prevention interventions.

-

In the economic domain, there is growing evidence for the beneficial mental health impacts of cash transfer programmes as a poverty alleviation instrument.19

-

In the neighbourhood domain, after-school programmes and recreational activity have been shown to improve self-esteem, self-confidence and increased pro-social behaviours.

-

In the environmental domain, psychosocial interventions targeting children exposed to traumatic events have been shown to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

-

In the social and cultural domain, increased school enrolments and higher educational attainment have been shown to reduce depression in adolescence.

Implications for policy and practice

In the South African context, mental health policy and services have been largely focused on providing treatment for adult populations, mainly through hospital-based services.20 There is a key gap in policy interventions that address the upstream social determinants of child and adolescent mental health, that would lead to a reduction in the burden of mental health conditions at population level. The NMHPFSP implementation strategies must take a whole-of-society approach in co-ordinating sectors that can address these upstream social determinants and improve the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents. This work should actively engage the relevant department as a central mechanism through which to harness resources and embed a mental health orientation to intersectoral work.

To promote this whole-of-society approach, it is vital that future research in South Africa evaluates interventions that combine components to address the social determinants. For example, interventions that provide immediate poverty relief, such as the Child Support Grant, could be combined with socio-emotional learning programmes in schools to promote the resilience of children and adolescents and prevent mental health conditions. Food security, safe communities, access to good quality education, and opportunities for youth employment are all essential for promoting mental health and creating an enabling environment in which children can thrive.

Adopting a life-course perspective

It is also crucial to adopt a life-course perspective to examine the onset of health problems, and to understand how health disparities develop and are amplified, mitigated or reproduced across generations.21 Specifically, this perspective deepens understanding of how social risks and opportunities create vulnerability or resilience at each life stage, and how they accumulate or are reduced across lives and generations.21 A life-course perspective shifts understanding from simple, linear explanations to a perspective that acknowledges that mental health is complex, interactive, holistic, and adaptive.22

Child and adolescent health and development is consecutive, with what happens during one age period being influenced by what happened previously. The concept of developmental cascades is useful here to describe how functioning in one domain of behaviour may ‘spill over’ and affect other domains.23 For example, a child living in an environment characterised by violence may develop a heightened sensitivity to danger cues which are essential to protect themselves from such violence. However, when they enter school, the resultant anxiety may cause distraction and an inability to focus, resulting in poor grades, reduced educational achievement, and increased chances of school drop-out. Developmental cascades and a life-course perspective provide a way of showing how both ordinary and extraordinary experiences may ‘get under the skin’.24

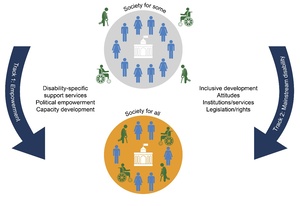

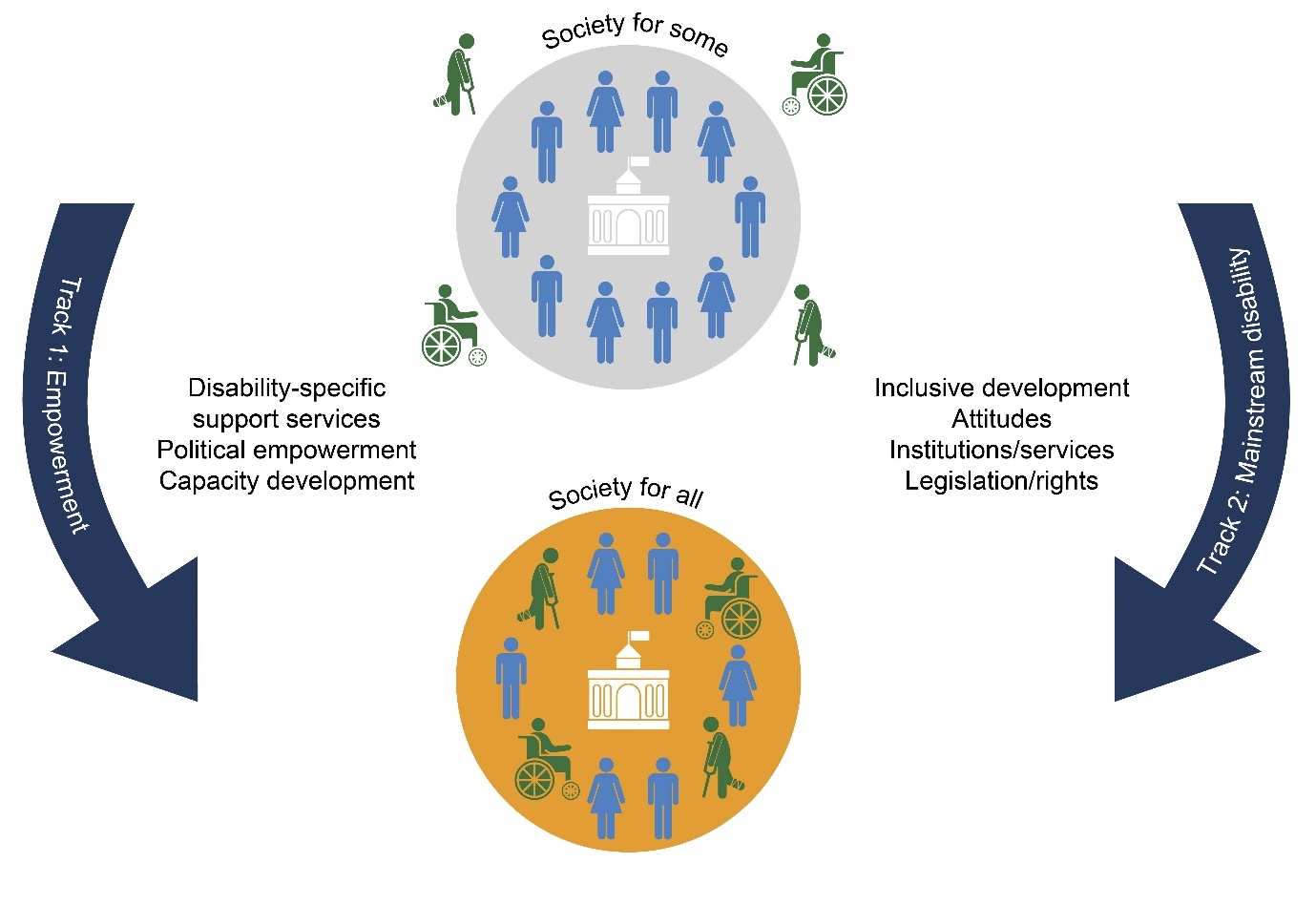

Implementing a twin-track approach

Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities25 defines persons with disabilities as “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others”.

Given the early age of onset of mental health problems or disorders, the risk for psychosocial disability with untreated conditions and the higher co-occurrence of psychosocial issues/disability with other disabilities, a shift is needed to extend the disability focus of the NMHPFSP implementation strategies beyond psychosocial disability to include mental health concerns affecting on all children with disabilities. This includes adopting a twin-track approach across the life-course, focusing on: (1) mainstreaming disability-sensitive design, implementation and evaluation of programmes, and (2) providing targeted interventions for disability-specific mental health-related supports to promote mental well-being and recovery of children with disabilities.26

Adequate funding of services must therefore provide for disability-specific programming. Co-ordinated financing and workstream mechanisms are needed across the social cluster to enable measurable intersectoral collaboration in mental health-related initiatives across departments. Although disability rights are enshrined in the Constitution of South Africa, and sectoral disability policies give direction to effect this, it has been suggested that disability legislation is needed to enforce cross-sectoral disability inclusion in policy implementation.27

The NMHPFSP highlights self-representation of service users in policy implementation. This must be extended to appropriate inclusion of the voices of children living with psychosocial and other disabilities through research and public participation initiatives.

Strengthening child and adolescent mental health services and systems

Child and adolescent mental health services and systems (CAMHSS) encompass the services that are accessible to children and adolescents for their mental health care and the systems within which these services are nested.28 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a health system includes “all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health”.29(p2) The six WHO health system building blocks (health service delivery, health workforce, information systems, access to essential medicines and technologies, health financing, and leadership and governance) provide a framework for understanding health systems.29 It is important to note that CAMHSS extend beyond the NDoH to include the Departments of Social Development, Basic Education, and Justice.

Child and adolescent mental health services in South Africa follow the WHO tiered model of care, promoting the integration of mental health services into general health services at the primary care level.1,30 This model, first adopted in the NMHPFSP 2013─2020, emphasises decentralised, community-based care. In this model, primary care clinics and community health centres form the first line of formal care, offering services for uncomplicated mental disorders, while more complex cases are referred to general hospitals.30 Highly specialised care is reserved for severe and complicated cases.30

State of child and adolescent mental health services and systems in South Africa

Despite the NMHPFSP’s advocacy for decentralised mental health services since 2013, South Africa’s mental health landscape remains overwhelmingly hospital-centric.31 This disproportion is starkly illustrated by the national mental health care budget, where a staggering 86% is allocated to in-patient services, leaving a mere 17% for out-patient care, of which only 8% filters down to primary care.32 In regions like the Western Cape, the primary care uptake for CAMH services is woefully inadequate, with children and adolescents comprising less than 5% of primary care out-patient visits in 2016.33 Rural areas fare even worse; for example, in the Amajuba District of KwaZulu-Natal, primary-level CAMH services were non-existent in 2019.34 Even when accessible, these services often fail to meet the specific needs of young people, with children and adolescents frequently being treated alongside adults,33,34 a practice that is far from ideal.35

The concentration of the CAMH workforce at higher levels of care exacerbates the issue. While multi-disciplinary teams are available at specialist psychiatric hospitals, they are not as accessible at general hospitals and primary care facilities.33,34 In South Africa, primary care is predominantly nurse-led,36 yet the nursing curriculum includes minimal mental health training, with virtually no focus on child and adolescent mental health. This oversight represents a missed opportunity for early detection and intervention. A recent study conducted in Cape Town highlighted CAMH as the top training need for Professional Nurses.37 However, the District Health Information System’s sole CAMH-specific indicator is the child and adolescent suicide rate,1 and the lack of comprehensive data impedes effective planning, evaluation and service improvement.38

Leadership and governance for CAMH are critical yet severely lacking at the national level. Despite CAMH having been on South Africa’s policy agenda for two decades, effective intersectoral collaboration systems and implementation plans are absent at the district and provincial levels. Financially, CAMH services suffer from a lack of dedicated funding with no ring-fenced budget, resulting in its low prioritisation compared to adult mental health and general health care. This financial neglect significantly hampers the delivery of effective CAMH services, contributing to the systemic challenges faced in providing adequate care for the nation’s young people.

Strengthening CAMHSS: lessons from the Western Cape

In the Western Cape, a provincial CAMH lead was appointed in 2021, resulting in the establishment of a CAMH service-strengthening team with a ring-fenced budget allocated to the project, and portfolios focused on early intervention, training, psychological services, digitalisation and outreach, and competencies and packages of care. Until recently, CAMH training in the Western Cape was anecdotal, but with the introduction of this team, more formalised training sessions have been conducted. A mapping of current psychosocial services was also conducted, providing valuable insights into existing resources and gaps. In parallel, a competency framework for medical officers at the primary care level was developed. This framework is based on the Academy of Science of South Africa competency framework38 initially designed for adult mental health, and has been adapted to meet the specific needs of CAMH. The team also works closely with the developers of the PACK Child guideline,39 ensuring that commonly seen presentations and conditions are not overlooked.

A centralised outreach service was established, featuring a senior medical officer serving as a mobile outreach clinician who is linked to all three specialised units. This officer assists general hospitals during crises involving children or adolescents, provides management guidance, teaches hospital staff, and triages waiting lists to prioritise the sickest children. This approach allows for timely treatment of the most critical cases and reduces unnecessary referrals to specialist units. Additionally, an in-depth analysis of the maternal─infant journey through midwife obstetric units identifies areas for improving infant mental health and for early detection and intervention of mental and neurodevelopmental disorders.

This concerted effort underscores the importance of deliberate health system strengthening activities focused on CAMHSS. The initiatives taken in the Western Cape illustrate how targeted strategies can significantly enhance service delivery and address the specific needs of children and adolescents within the broader health system. There should be a shift from seeing CAMH as a highly specialised discipline reserved for the apex pyramid in the WHO optimal mix of services, to a community-based speciality that brings CAMH close to where people live. Perhaps the NDoH could support provinces to develop context-specific provincial teams, within resources, to effect a co-ordinated district-to-specialist team approach.

Support for children of parents with mental disorders

In addition, it is important to recognise that children of parents with mental disorders are at heightened risk of developing mental health problems. Many blame themselves for their parents’ mental illness, or take on excessive responsibilities at home, or simply struggle to cope with the stigma, isolation and trauma of bearing witness to their parent’s illness. These children have been prioritised in prevention programmes in the Netherlands, Norway and Australia,40–42 which include interventions such as family assessments to identify children at risk, providing children with age-appropriate information about mental illness, strengthening school and social support, minimising family dysfunction, and a statutory duty to report cases of abuse and deliberate neglect. Similar guidelines should be established in South Africa to ensure that adult services incorporate proactive measures to identify and support children of parents with mental illness.

Using schools as nodes of care and support

Educational institutions are well placed to play a pivotal role in supporting the mental health of children and adolescents.43 Increasingly, children are accessing early childhood education facilities, with even more attending primary schools, and significant numbers are enrolled in high schools and tertiary institutions.44 Therefore, educational institutions in South Africa serve as vital centres of care. These institutions possess existing infrastructure and are typically well integrated within the communities they serve, as well as with local and provincial governments that regulate their operations.43 As critical contact points, schools facilitate interactions between educators, students, parents, caregivers, and various community organisations and services, with the potential to create a comprehensive support network for learners.45

Stigma associated with mental health problems often prevents young people from accessing the support they need. As such, school-based interventions that are effectively delivered by mental health professionals, teachers, para-professionals, lay counsellors, and peers, are often more accessible than specialised mental health services.46 Evidence suggests that high-quality teacher─student relationships can serve as a crucial protective factor for vulnerable children.47,48 Moreover, learners who feel connected, respected and valued in their school have positive outcomes such as psychosocial well-being, and are less likely to engage in risk behaviours or experience mental health problems.49

Poverty, violence, and social and gender inequality can profoundly influence schools’ operations in ways that compromise child and adolescent mental health,50 for example, by exposing children and adolescents to negative experiences, including bullying51 and corporal punishment.52 Additionally, many schools are overburdened with limited capacity to provide comprehensive mental health support.53

The WHO’s Health Promoting Schools framework underscores the critical role of schools in creating healthy and safe spaces for teaching and learning.54 This framework advocates for a holistic approach by integrating health promotion into the school curriculum, engaging communities and families who significantly influence child and adolescent health, and addressing both the physical and psychological environments of schools.43

Mental health support in South African schools must be tailored to the developmental stages of learners, and provide support across the mental health continuum from promotion of positive mental health to prevention of mental health conditions, as well as access to treatment and recovery services.43 While comprehensive policies exist to address these needs, challenges in implementation persist, necessitating ongoing attention and improvement from early childhood development (ECD) programmes through to high school.43 For example, while ECD policies make provision for health screening and support services, they require a stronger focus on the early identification and referral of mental health problems.43 Strengthening educators’ capacity to identify behavioural concerns has shown effectiveness in resource-constrained settings,55 and ECD centres serve as crucial hubs for connecting parents and caregivers with necessary services.

Primary school policies mandate health screening, psychosocial support and linkages to Primary Health Care facilities56 and the curriculum includes mental health education. Future investments should prioritise training for educators and healthcare providers to effectively implement these policies. Addressing bullying and enhancing school connectedness remain critical objectives.43

In secondary schools, policies again emphasise health screening, psychosocial support, and school safety, along with mandatory counselling for pregnant and parenting learners.43 Collaborating with community-based initiatives can mitigate implementation challenges.43 For example, peer support groups, sports, and arts-based programmes can build resilience and social connectedness among adolescents. Additionally, leveraging digital health tools can complement these interventions; mobile apps, SMS-based support, and youth-focused social media campaigns offer discreet and accessible help-seeking options for adolescents. Implementing such youth-friendly initiatives is vital for reaching vulnerable youth who may not otherwise seek formal services.57,58

Tertiary institutions play a crucial role, and although a comprehensive national policy for mental health in higher education is yet to be developed, individual institutions have developed their own frameworks to support students facing mental health challenges.

The following key areas have been identified to enhance mental health across the educational system:

-

Transition periods between educational phases (for example between primary and secondary school) are particularly stressful for learners, and targeted interventions are needed to ease these transitions effectively.59

-

Addressing systemic issues such as racism, sexism and discrimination within educational settings is imperative. Initiatives like Teaching for All, which has been implemented in South Africa, exemplify efforts to mitigate these challenges.60

-

Supporting the well-being of educators is also crucial, given their stress levels and perceived lack of readiness to handle mental health issues.61,62

-

Furthermore, there is a pressing need to integrate learners with disabilities into mental health support frameworks, as they are disproportionately vulnerable to developing mental health disorders.63

Despite the challenges faced by schools and educational institutions, leveraging existing resources and evidence can pave the way for incremental improvements in mental health support for young people across South Africa.

Finally, it is also important to consider children and adolescents who are not part of educational institutions, and the crucial role played by community-based interventions such as Waves for Change in complementing school-based programmes.

The role of community-based interventions: Waves for Change

Waves for Change (W4C) offers mind-body therapy through a 12-month intervention targeting chronic trauma, emotional regulation, a sense of belonging, and instilling a sense of purpose. Participants meet once a week for a three-hour session that includes mental health promotion and surfing. Recently, W4C piloted a programme specifically for neuro-diverse children, with initial findings showing promise. The general structure of the sessions includes an energiser (physical activity), emotional check-in, breathing and meditation, a surfing lesson, and debriefing.64 These interventions are delivered by youth coaches, using five pillars: a physically and psychologically safe space, a caring adult, fun physical activity, the opportunity to learn new social and emotional skills, and referral to other services when needed.

Given the breadth of challenges and opportunities discussed across the health, education and community sectors, it is helpful to draw together these key actions into a single overview. Table 1 provides a summary of key recommendations to support child and adolescent mental health in South Africa at policy, school, health facility, and community levels.

Conclusion

In a context of climate breakdown, poverty and political fragility, children and adolescents are growing up in a ‘world on fire’.65,66 Globally, this can be seen in increased mental ill-health and feelings of hopelessness. In South Africa, the caring capacity of families and community networks is under increasing pressure, with four in every 10 children now living below the food poverty line,67 while austerity cuts are eroding children’s access to essential health, education and social services.68 Amid these challenges, it is critical to prioritise early investments in child and adolescent mental health in order to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty and ill health. To deliver on this vision, South Africa must invest in building an ecosystem of support69 ─ one that bridges health, education and social development systems, and that builds a strong foundation for health and development across the life-course.