Introduction

South Africa has among the highest burdens of common perinatal mental health conditions (‘perinatal’ being the period from when a woman becomes pregnant to one year postpartum). Between 16% to 50% of women experience depression, stress or anxiety,1–3 and 10% are at high risk of suicide.4

This public health crisis, underpinned by apartheid-originating inequalities, is driven by social determinants such as poverty, food insecurity, gender and racial disparities, violence, and social isolation.5,6 In turn, mental ill-health traps women in vicious cycles of socio-economic adversity,7 with multiple transgenerational impacts8 such as double the odds for low birth weight and pre-term birth, and other long-term impacts on child and adolescent wellbeing.9

Evidence suggests that in resource-constrained settings, mental healthcare services may feasibly and effectively be delivered by non-mental health specialist service providers, often integrated within the context of Maternal and Child Health platforms.10–12

In recent years, the South African health policy environment has shifted substantially to foreground the provision of mental health care within maternity care platforms. The 2021 South African Maternal Perinatal and Neonatal Policy includes “maternal and mental psychosocial support, including detection and management of maternal mental health disorders”, as one of “16 essential life-saving intervention packages”.13(p32) The National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023–2030 underscores the critical need for mental health care to be integrated within general health services, and acknowledges perinatal women as being particularly vulnerable.14 The release of the national Integrated Maternal and Perinatal Care (IMPC) Guidelines for South Africa in October 2024 marked a significant breakthrough with three new chapters: Respectful maternity care; Maternal mental health; and Intimate partner violence and domestic violence.15

The new IMPC Guidelines follow the principles set out in the 2022 World Health Organization guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in Maternal and Child Health Services16 and correspond to other key South African guidelines such as Adult Primary Care17 and the 2019 Standard Treatment Guidelines.18

In 2021, the National Department of Health (NDoH) and National Treasury commissioned an assessment of the Mental Health Investment Case for South Africa. This showed that the government’s return on investment would be R4.70 for every R1 spent on addressing maternal depression, which thus represents the highest return for all mental health conditions that were analysed.19

Despite policy advances, integration of mental health care into primary maternity care remains limited. No dedicated or designated staff are available to provide psychosocial support, and existing maternity care staff face high levels of burn-out and compassion fatigue.20 Levels of disrespect and abuse of service users by staff appear to be very high.21 Barriers include high patient volumes and lack of training in the detection and management of mental health problems.22,23

The Perinatal Mental Health Project (PMHP) the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Public Mental Health has for, 12 years, operated a maternal support service (MSS) at the Hanover Park Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU). This service is funded by private grants, donations, and in part, the Department of Social Development. Using the PMHP as a case study, the objectives in this paper are to:

-

demonstrate how a stepped-care maternal mental health service model can be feasibly integrated into primary-level maternity care in South Africa;

-

share the practical lessons, adaptations and efficiencies gained over a 12-year implementation period within a high-adversity setting; and

-

illustrate the enabling factors and challenges of integrating perinatal mental health care into public health systems.

The goal is to contribute actionable insights for policy-makers, programme implementers and health planners on how to design, adapt and scale up maternal mental health services in real-world, resource-constrained contexts.

Case description: the PMHP maternal support service

Hanover Park is located about 20 kilometres from Cape Town’s central business district. It was designed under the Apartheid regime’s Group Areas Act to house forcibly displaced Coloured communities who still face socio-economic marginalisation and systemic inequalities today.

The area is densely populated, with high levels of unemployment and poverty. The community faces endemic gang-related violence and substance abuse. In 2012, the PMHP undertook a cross-sectional study among pregnant women at the Hanover Park MOU to establish their socio-economic profile and prevalence of mental health conditions. The findings indicated that 55% were unemployed and 42% reported food insecurity in the past six months; 22% were diagnosed with a major depressive episode, 17% with anxiety disorders, 11% with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 18% with alcohol and other substance use disorders. Current suicidal ideation was reported by 12%.2,4,24,25

The MSS provides free, tailored mental health and psychosocial interventions to women during their pregnancies and up to a year postnatally. The service is integrated into the primary-care level MOU at the community health centre (CHC). Women from Hanover Park and surrounding areas, including historically Black African-designated townships, can access the MOU for pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care if they have minimal obstetric risk factors.

The MSS rationale, design and pilot have been previously described.26 Over time, elements have evolved or been added based on: (1) experience of PMHP service provision at other sites that are no longer operational; (2) contextual factors such as policy and guideline changes, and (3) PMHP monitoring and evaluation processes.

Approach

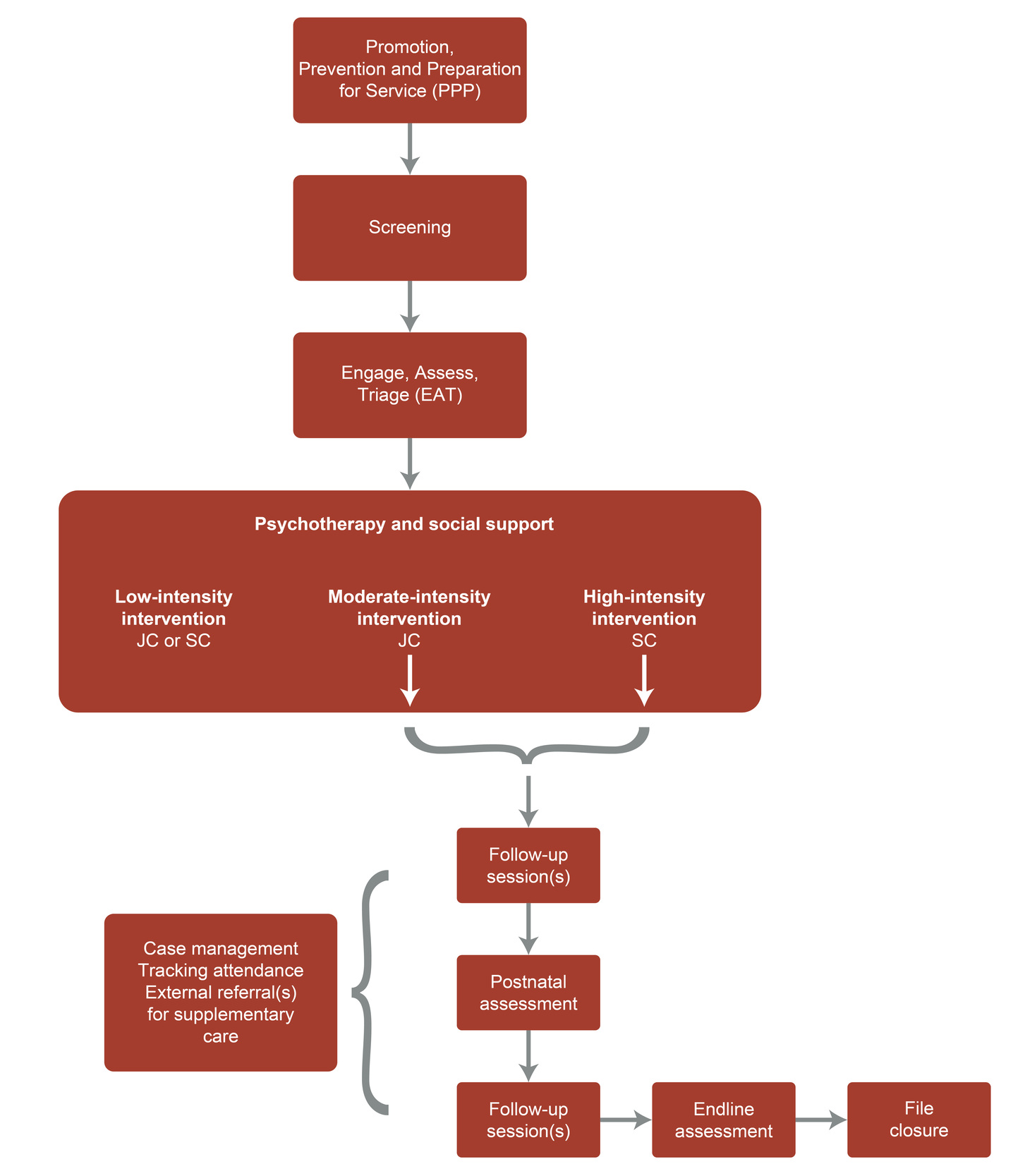

The current model combines both collaborative care and stepped-care service design principles, and consists of multiple components.

PMHP employs two full-time registered counsellors ─ one senior and one junior ─ to provide on-site services. These counsellors are provided with technical and administrative support by PMHP staff with governance by PMHP leadership. A simplified form of the MSS design is depicted in Figure 1.

The core components of the model are described as follows.

Collaboration with maternity staff

MSS staff work closely with MOU midwives, nurses, and administrative staff to integrate mental health care into routine maternal health services. This partnership is founded on open communication, ensuring that both maternity and PMHP staff can effectively respond to evolving needs, such as changes in MOU staffing and procedures, NDoH policies, and modifications in MSS. PMHP provides top-up training and sensitisation programmes to equip staff with the skills to identify and support women experiencing psychological distress, to make effective referrals, to engage empathically, and to manage their own psychological wellbeing.

Service design challenges and improvements are addressed through a co-design approach. This entails conducting workshops on monitoring and evaluation findings where achievements are celebrated and challenges are discussed using and egalitarian framework.27 Over time, these activities foster shared ownership and iterative enhancements of service delivery. This collaborative approach has yielded significant efficiencies in the service with regard to screening coverage, timely and appropriate referrals, tracking of service users, and respectful maternity care.

Mental health promotion, prevention and service preparedness

Prior to instituting this component, women were hesitant to engage with the screening and counselling services offered. We attributed this to high levels of mental health stigma and low levels of mental health literacy among pregnant women, as noted by colleagues at a similar MOU in Cape Town.28 We were also concerned about the women who screen negative for depression, stress or anxiety, as they may not reach threshold criteria but may nevertheless be experiencing distress and thus could benefit from psycho-education. For this reason, promotion, prevention and service preparedness (PPP) group sessions were introduced to improve these women’s engagement with the service and to promote the psychological wellbeing of other women. Counsellors conduct these informal discussions in the waiting area of the MOU daily. The sessions aim to:

-

promote awareness of maternal mental health and emotional well-being;

-

prevent the escalation of mental health difficulties by equipping women with self-care strategies;

-

prepare women to access the MSS when needed, and

-

normalise conversations about mental health and reduce stigma.

The sessions have been well received, with many women actively engaging in discussions, requesting available information leaflets, and expressing a greater willingness to access services following participation.

Initial screening with a locally validated, ultra-brief tool

Universal screening by maternity staff or MSS counsellors originally entailed an adapted version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)29 and a PMHP-developed risk factor assessment (RFA) tool.30 The EPDS proved to be unfeasible for maternity staff in terms of the time needed for administration and the complex scoring system. The multiple-choice structure and use of culture-bound idioms rendered the tool unsuitable for South African women.

The PMHP developed31 and validated32 an ultra-brief screening tool, the Maternal Distress Tool (MDT) for maternity staff to use as an initial screen for identifying women who may require mental health support. The tool has since been incorporated into the 2024 National Integrated Maternal and Perinatal Care Guidelines15 and into maternity case records.

After this was introduced, MSS and MOU staff decided that the Unit personnel would administer targeted screening of vulnerable groups such as adolescents, women with previous mental health problems, women experiencing gender-based violence, those living with HIV, and women about whom MOU staff were concerned. This, together with the additions to the service of PPP and EAT (as shown in Figure 1), yielded several efficiencies in terms of service uptake.33

From the beginning of 2024, a NDoH mandate for universal screening introduced challenges in managing the increased number of eligible women accessing the MSS. The target groups previously identified by PMHP are still referred for assessment, irrespective of their MDT scores. Some women undergo screening at the first antenatal booking visit at the MOU, while others are screened later in their pregnancies, after transfer from Basic Antenatal Care clinics, or when attending the MOU for postnatal care.

Engagement, assessment, and triage sessions

On the basis of these referral criteria, women are offered an EAT session with the junior counsellor, usually directly after MDT screening. These sessions were instituted in order to optimise use of the counsellors’ time. Previously, all women who qualified on the basis of the screening received the same intensity of care from the counsellors. It was noted that the counsellors did not have the time to accommodate women with higher intensity needs. In addition, there was concern that without a personalised, brief engagement with the service to address concerns and misunderstandings, many women who screened positive for distress would not attend the counselling appointments made for them.

In the EAT session, the counsellor develops a rapport with the women, repeats the screening to validate the score, and assesses for level of distress and for psychosocial risk factors using the RFA. Together, the counsellors and women identify existing resources available and, taking all of these into account, assign a level of intervention based on need. At the end of the EAT session, women with low levels of need receive a brief 10–20-minute intervention focusing on listening, containment, psycho-education and if needed, referral. Women with intermediate levels of need are offered an appointment with the junior counsellor. Women with high levels of need are offered an appointment with the senior counsellor. This process ensures that women receive personalised care and are more likely to attend scheduled appointments, while counsellor time is rationalised for those with higher levels of need.

On-site psychotherapeutic and social support interventions based on levels of need

A range of psychotherapeutic interventions is provided to women with medium to high levels of need. Where feasible, these appointments are arranged to coincide with subsequent scheduled MOU visits, which reduces the need for women to overcome logistical challenges associated with attending for care. The sessions last for 20–60 minutes, and the frequency and timing of sessions offered are based on the women’s needs. The sessions are usually held in-person, although WhatsApp or telephone platforms are available should this be more suitable for the women. Most sessions held are with individual women, but couple, mother─infant, or family interventions may occur as required, and with the women’s permission.

The evidence-based therapeutic modalities employed are an eclectic mix of: cognitive behavioural techniques, psycho-education, grief/bereavement support, bonding intervention (in utero), birth preparation, mothering intervention (exploring the woman’s experience of being mothered), problem-solving, behavioural activation, mindfulness-based techniques, emotion-focused techniques, suicide and impulse risk management, relationship counselling, family and couple counselling, trauma debriefing, and culture-related, crisis, economic and gender-based violence interventions.

Maternal─infant interventions are embedded within the psychotherapeutic offerings, ensuring that the psychological needs of both the mother and infant are met. These include: mentalisation, co-regulation, postnatal bonding intervention, parenting discussions, and infant developmental processes. When possible, a structured follow-up assessment is conducted between six and 15 weeks after the birth. This session enables the counsellors to develop a postnatal care plan and assess resolution of self-reported problems, perceptions of the birth experience, mother─infant attachment, depression and anxiety symptoms, problems with functioning, general perceptions of current life experience, and perceptions of the MSS. Women who do not attend booked sessions are monitored and tracked through a tracking system. Records are kept of those cancelling, transferring to other facilities, or not attending.

Collaborations for case management

The MSS collaborates with social workers and various community organisations to provide comprehensive case-management for women. Counsellors facilitate access to services that offer food security, shelter, parenting support, domestic violence and child protection, social grants, doula services, and income-generating activities. When required, referrals are also made to psychiatric services for psychiatric assessment and prescription of psychotropic medication.

Co-ordinating these referrals is time-intensive for counsellors, requiring ongoing liaison, tracking and follow-up to assess uptake and impact. Growing and maintaining a network of community partnerships, and updating a directory of resources, are key aspects of their work. This time investment ensures impactful care by addressing the psychological and socio-economic factors that influence maternal mental health.

Monitoring and evaluation

Counsellors, administrators and managers all contribute to a structured monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process to ensure service effectiveness and quality. The M&E database is registered with the University of Cape Town’s Health Faculty Research Ethics Committee (R032-2019) and includes:

-

service delivery data (number of women screened, referred, and receiving mental health support);

-

documentation of counselling sessions (including intensity level, duration, format and intervention types used) and referral uptake; and

-

key socio-demographic data and clinical indicators to track trends and identify emerging needs.

Outcome and impact assessment involves:

-

the tracking of psychological distress levels and service-user progress using screening tools and standardised surveys;

-

monitoring of referral outcomes; and

-

collection of feedback from service users to identify service strengths and areas for improvement.

Reporting, adaptation, and continuous improvement entails:

-

reports summarising key findings, service trends and impact indicators, which are distributed to a range of stakeholders through regular face-to-face engagements for discussion, and

-

an iterative improvement cycle to ensure refinement of intervention strategies in response to changing needs, policy shifts, and staffing dynamics.

Additional mental health screening tools and surveys were incorporated into the database in 2024 and early 2025 to improve the ability of the data to reflect changes over time. These include an assessment of functioning modified from the functioning item on the Patient Health Questionnaire 9,34 the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale,35 and the Kimberly Mums Mood Scale,36 all of which underwent cognitive testing and adaption by PMHP for the population served. This information will be analysed when the sample size allows for inferential statistics to be conducted.

Prioritisation of staff well-being and supervision

The service model includes weekly individual supportive clinical supervision of MSS staff to mitigate the emotional toll. Additionally, several mental health promotion activities have been integrated into the PMHP for all staff, including access to free mental health support, team-building activities, and quarterly mental health days. Staff also have access to a set number of days for continuing professional development opportunities. These elements have helped to prevent burn-out and have promoted retention of staff, thus enhancing the sustainability and quality of the service.

Results

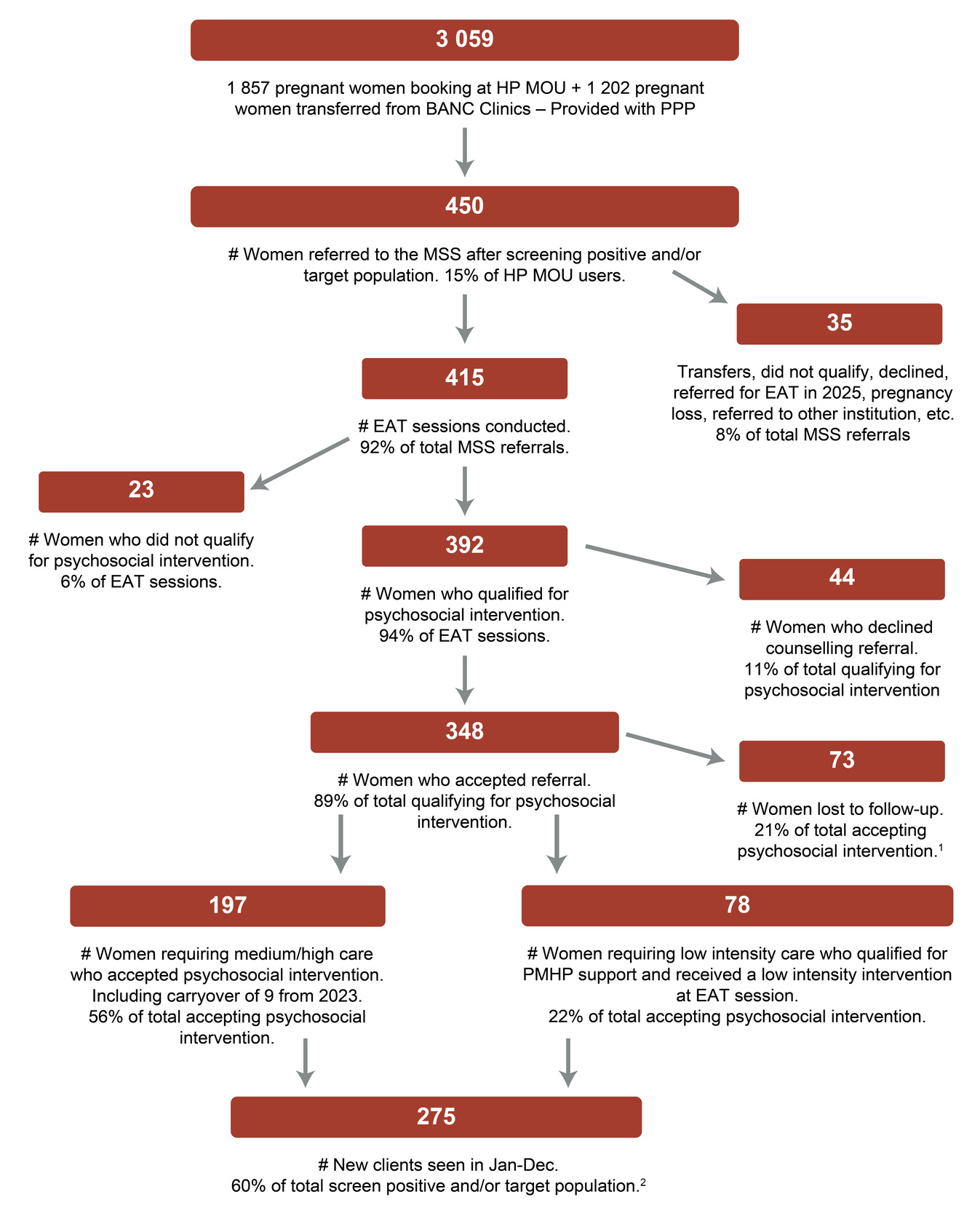

During 2024, maternity staff referred 450 of the women who attended the MOU for antenatal care to the MSS. Referral was based on a positive MDT screen or if a woman was from a vulnerable population group. A total of 275 new MSS service users were seen with a mean of 3.4, a median of 3, and a mode of 2 sessions attended. Details are provided in Figure 2.

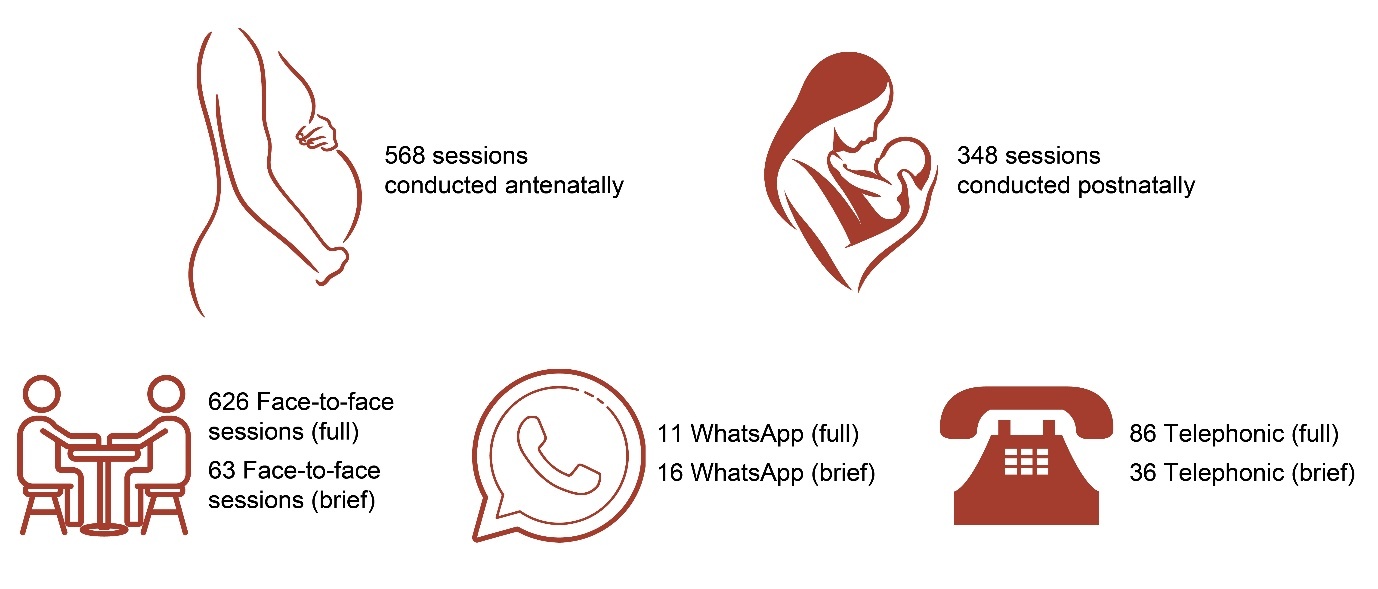

Figure 3 depicts a breakdown of the 916 sessions provided by perinatal period (antenatal n= 568 and postnatal n=348). The duration (full and brief), and format (face-to-face, WhatsApp and telephonic) are depicted for 838 sessions, and which exclude the low-intensity interventions for 78 women.

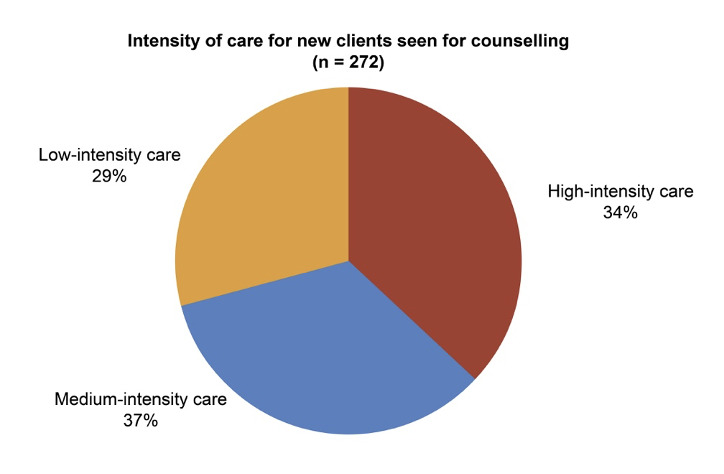

Figure 4 shows the intensity of care received by new clients during 2024.

During the year, 178 referrals were facilitated to external organisations for complementary services: 53% to non-government organisations (NGOs), 25% to Department of Social Development services, and 22% to public health services.

Postnatal follow-up assessments were completed for 69 women in 2024. For the degree of resolution of their presenting problems, across all problem categories (primary support, social environment, physical health, mental health, lifecycle transition), 37% reported complete improvement, while 23% reported partial resolution. For these 69 women, a comparison of their perceptions of how they were feeling before and after the intervention is illustrated in Table 1.

A selection of quotes from service users, as captured at the postnatal assessment, is provided below.

[I] would recommend the counselling. Helps a lot. Yoh, it’s a good thing when you think what happened in your past. You can share. I don’t have friends. I got you to talk about anything. I’m happy I have you in my life, not feeling so heavy now.

[I] could speak about troubles. Black people don’t talk about feelings. I don’t speak to anyone. Would suggest it for a trusting stranger, advice, family worry about you, speak and work through it, mom will worry.

I was so scared in this pregnancy because of what has happened before. I was not okay, but I enjoyed talking and it was so helpful for me.

I feel so much better now. I am not as angry as before. I was judging myself, stressing, not sleeping, not talking to anyone. I kept a lot to myself, but since I started speaking, my mind is clear and working. I can think of a plan.

Discussion

The MSS demonstrates the feasibility of integrating mental health care within a primary-level maternity care setting. Outcomes data from 2024 resonate with indications of positive impact that have been documented in qualitative studies conducted with MSS service users.37–39 The service model has undergone refinements over more than a decade to improve efficiency, accessibility, and service-user outcomes. However, challenges remain in scaling and sustaining the model, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Challenges and limitations

Capacity and workforce constraints

The cadre of provider is a critical consideration. The MSS model employs registered counsellors, whose tertiary-level training enables them to integrate diverse psychotherapeutic modalities, contributing to symptom improvement or remission. However, this approach comes at a significant cost, as the expenditure for training and remuneration of registered counsellors is substantially higher than for community health workers (CHWs) or peer providers.

While randomised control trials (RCTs) in other low- and middle-income countries have shown that CHWs and peer providers are effective in delivering perinatal mental health interventions, findings from South Africa raise concerns about their ability to engage in effective psychotherapeutic modalities. Specifically, a RCT in Khayelitsha40 and implementation science research in Cape Town informal settlements41 demonstrated limited effects of psychosocial interventions provided by CHWs, which raises concerns about the feasibility of relying on lower-cost cadres for mental health service delivery in South Africa. For national replication, a cost-effective yet adequately skilled workforce is needed to support widespread implementation.

Screening mandates and service capacity

The recent inclusion of the MDT in the national guidelines and maternity case records represents a significant advancement for early identification and intervention of perinatal mental health problems. However, the opt-out provision, which allows for screening to be omitted if services are unavailable, may lead to avoidance of mental healthcare provision by staff. Additionally, universal screening can create logistical challenges in triaging and managing large numbers of women identified as needing support, particularly in settings where mental health and social support services are already stretched.

Related contextual factors influence the conundrum of ‘to screen or not to screen’.42 Brown, et al.23 described that mental health is not a priority for many managers and senior health officials overseeing maternity services. This, combined with insufficient provider training, limits the integration of mental health screening care into primary-level maternity care. Many maternity providers in South Africa report that high patient volumes limit their ability to conduct mental health assessments. Some avoid screening due to time constraints or to a perceived lack of mental health expertise. Similarly, Abrahams, et al.22 found that while some providers recognise the importance of screening for common mental disorders, they often feel unprepared to manage positive cases. They express discomfort with discussing mental health issues, and report that referral pathways are unclear or inconsistent. Furthermore, pregnant women may avoid disclosing their distress due to concerns about stigma, confidentiality, or the availability of services. In settings where there are inadequate resources available to ensure mental health care and follow-up, it may be ethically problematic to conduct screening.

Referral pathways and socio-economic barriers

A key component of the MSS is linking women to social support services. However, referral co-ordination is time-intensive, requiring liaison, tracking and follow-up. Additionally, external service availability and reliability fluctuates due to funding and resource constraints, thereby affecting continuity of care. Socio-economic hardships, including transport costs, lack of safety, and caregiving responsibilities, further limit some women’s ability to engage fully in interventions.

Data limitations and future analyses

The M&E process has evolved to capture service-utilisation trends and rudimentary service-user outcomes. The findings are largely descriptive, limiting the ability to generalise conclusions about service impact. However, the inclusion of more complex mental health screening scales and socio-economic indicators in 2024–2025 is expected to enhance data robustness and strengthen evidence-based recommendations for scaling the MSS model.

Replicability and scalability

The PMHP MSS offers a partly scalable model for integrating mental health care within maternal health services.

Key facilitators of replicability are:

-

use of a validated, ultra-short screening tool (i.e. the MDT);

-

a stepped-care approach, allowing for flexible and resource-efficient service delivery; and

-

collaboration with maternity staff and local support services, fostering shared responsibility for mental health integration.

Recommendations for scaling

A co-ordinated strategy from the NDoH, in collaboration with the Department of Social Development and the NGO sector, is needed for sustainable maternal mental health services.

We suggest that the NDoH engages in a multi-level approach that includes the following:

Adequately resourcing frontline providers

-

Expansion of training programmes (undergraduate or in-service, such as ESMOE43) to equip maternity health workers to provide empathic care, screening for mental health issues, first-level support, and appropriate referral.

-

Implementation of ongoing competency training and assessments to ensure that maternity health workers and other relevant providers can address common perinatal mental health concerns.

-

Exploration of task-sharing approaches with midwives and nurses to be trained in psychotherapeutic modalities, and/or employment of a greater complement of registered counsellors within the health system.

-

Supplementing these actions with mental health promotion activities provided by CHWs. An example from The Gambia reports that collaborative music-making facilitated by local women from the community improved symptoms of distress.44

-

Testing of hybrid models that combine CHWs’ involvement for women with low-intensity needs with registered counsellors, to provide oversight of CHWs and care for women with higher levels of need.

-

Provision of robust supervising and mentoring programmes for providers to support mental health-related responsibilities.

-

Strengthening of health workers’ wellbeing by embedding proactive and preventive approaches within the work environment to mitigate burn-out and improve the quality of care.

-

Involvement of human resource personnel to amend job descriptions and performance measures for maternity health workers to include mental health-related key performance areas.

Strengthening referral pathways

-

Creation of new and funding of existing referral options for women requiring psychosocial and more specialised mental health support, including existing structures developed through the Primary Health Care Re-engineering programme.45

-

Provision to NGOs of with financial and technical resources to ensure their sustainability, effectiveness and quality of care.

-

Development of standard operating procedures to streamline mental health care within maternal services and referral pathways.

Including relevant mental health service indicators

Incorporation of perinatal mental health service indicators into maternity care health management information systems to enable monitoring and evaluation of service provision.

Conclusion

These system-strengthening elements will require good governance, co-ordination, and financial investment. We believe that the cost of not investing in such responses is ethically and economically unaffordable. If these strategies are implemented, South Africa may realise the potential of integrated mental health services within maternity care, ensuring the holistic well-being of mothers and their children.