Introduction

The Mental Health Care Act 17 of 2002 (MHCA) provides for equitable access to efficacious mental healthcare services across South Africa, within available resources.1 The MHCA promotes care in the least restrictive environment, preferably in the community, and stipulates that services should be integrated into the general healthcare setting at all service levels, including Primary Health Care (PHC). Accordingly, the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2023– 2030 (NMHPFSP) promotes the availability of psychotropic medicines, as provided for in the Standard Treatment Guidelines (STG) and Essential Medicines List (EML), throughout the health system, with monitoring and evaluation of medicine utilisation.2

Access to effective psychotropic medicines has contributed significantly to the global movement towards de-institutionalisation.3 However, in South Africa, de-institutionalisation has occurred without appropriate community-orientated mental health care, resulting in homelessness, incarceration, and ‘revolving door’ admissions.2 Sustainable access to effective psychotropic medicines is essential if people with serious mental illness are to be integrated into their communities.

The aim of this paper is twofold: (1) to review national policy supporting access to psychotropic medicines of assured quality, safety and efficacy by the uninsured South African population, and (2) to examine psychotropic medicine utilisation by the provinces and nationally and explore equity in access and changes over time.

Method

The Medicines and Related Substances Act 101 of 1965 (Medicines Act)4 and National Drug Policy 19965 were reviewed with regard to psychotropic medicine access (i.e. medicines used in the treatment of mental disorders); non-psychotropic medicines used for the management of adverse effects were not included. The National Department of Health (NDoH) STG and EML for PHC, paediatric hospital, adult hospital, and tertiary and quaternary service levels ─ accessible on the NDoH website6 ─ were examined regarding the medicines available, indications for use, and prescriber restrictions.

The NDoH endeavours to have all EML medicines on national tender and therefore equally available to all provinces. Because patient-level data are not available in the public health sector, medicine procurement data were analysed as a proxy for medicine utilisation. Data were obtained from the National Surveillance Centre (NSC) for the calendar years 2019 to 2023. The NSC is a web-based tool developed in 2016 with the support of the Global Health Supply Chain Programme–Technical Assistance, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).7 The NSC links with provincial medicine depots and individual facilities to enable real-time monitoring of medicine availability at all levels of the supply chain. While there is a need to strengthen the use of the NSC to improve stock management, medicine procurement by provinces and institutions is accurately recorded for medicines that are on national tender.

One problem with relying on procurement data is that the reason for prescription and clinical profile of the end-user is not evident. As this study aimed to gain insight into medicine access for mental disorders, medicines were included in the analysis only if their indications for use in the STG are limited to mental disorders. Therefore, medicines commonly used for both mental and other health conditions were excluded.

NSC procurement data were expressed using the defined daily dose (DDD) per 100 000 uninsured population, per day, for each medicine or medicine group and province. The DDDs for each medicine formulation were obtained from the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.8 The DDD is a standard dose assigned to each medicine and medicine formulation according to its main indication for use, which facilitates comparative analysis between healthcare settings. The uninsured population per province was derived by subtracting actuarial estimates for medical aid coverage from mid-year population estimates for each year, as explained by Ndlovu, et al.9

Results

The findings from the review of medicine-related legislation and policy are presented, followed by analysis of procurement data.

Legislation and policy

Medicines and Substances Related Act 101 of 1965 (Medicines Act)

Section 22A of the Medicines Act4 governs the sale and supply of medicines in accordance with their prescribed schedule. In terms of section 37A of the Medicines Act, the Minister may, on recommendation by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), amend any schedule prescribed under section 22A by notice in the Government Gazette. Scheduling recommendations are made by SAHPRA principally according to the safety profile of the active pharmaceutical ingredient and dosage form in relation to the therapeutic indications for its use.

Medicines in Schedules 3 to 6 are only available upon prescription by an authorised prescriber (defined in section 22A (17) as “a medical practitioner, dentist, veterinarian, practitioner, nurse or other person registered under the Health Professions Act,1974”).4 While medical practitioners, dentists and veterinarians can prescribe all medicines in those schedules, within their scopes of practice, the other prescribers are limited to specific medicines within each schedule. Medicines may be scheduled as ‘prescription-only’ for several reasons, including the need for professional assessment and management of the clinical condition for which the medicine is indicated, and/or professional monitoring for potential toxicity, adverse events or dependence.10 Heightened potential for abuse or dependence, necessitating additional access control, differentiates Schedules 5 and 6 from Schedules 3 and 4. Although substances in Schedules 5 and 6 may be listed for prescribing by specialist nurses, no such listing has occurred to date, as no specialist register for nurses exists currently.11 PHC nurses in the public sector are provided with section 56(6) permits, in accordance with the Nursing Act 33 of 2005.12 Such nurses may prescribe medicines only up to Schedule 4.

Psychotropic medicines used in the treatment of mental and substance-use disorders are all listed in Schedule 5 (e.g. anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, lithium salts, benzodiazepines) or Schedule 6 (e.g. methylphenidate, methadone, buprenorphine). Additional restrictions are placed on any Schedule 5 or 6 medicines used for their “anxiolytic, antidepressant, or tranquillising properties” in that they may not be continued longer than six months without authorisation by a psychiatrist in addition to the initial prescriber (or by a second psychiatrist if the initial prescriber is a psychiatrist). While Schedule 5 prescriptions may be repeated for up to six months, Schedule 6 prescriptions are for a maximum of 30 days’ treatment.

National Drug Policy 1996

The National Drug Policy aims to facilitate universal health coverage in South Africa by ensuring “an adequate and reliable supply of safe, cost-effective drugs of acceptable quality to all citizens of South Africa and the rational use of drugs by prescribers, dispensers and consumers.”5(p3) The Essential Drugs Programme was developed within the Affordable Medicines Directorate in the NDoH to assist with achieving the aims of the National Drug Policy in the public health sector. To increase access to medicines at PHC level, the National Drug Policy recommends that prescribing is determined by competency rather than occupation, stressing the need for institutional and in-service training to ensure suitably qualified prescribers, and encouraging statutory councils to set continued competency requirements.

Two core functions of the Essential Drugs Programme are to select medicines for the EML and to draft standard treatment guidelines. The EML facilitates equitable access to medicine treatment across the country, while the guidance of the STG aims to strengthen rational medicine use. Importantly, the STG is not a comprehensive programme guideline, but is designed to support clinical practice with regard to the EML medicines. The quality, safety and efficacy standards of individual medicines are assured, as only medicines registered with SAHPRA may be included on the EML, and adverse drug reaction reports are monitored by SAHPRA.

The treatment of mental disorders was integrated into the EML and STG from the outset, with specific sections in the 1998 editions of the PHC, adult hospital, and paediatric hospital STG. Psychotropic medicines were integrated into tertiary and quaternary reviews in 2008, when the Tertiary and Quaternary Expert Review Committee was formed. Table 1 presents the essential medicines for mental and substance-use disorders in the current STG according to service level and clinical indication. All PHC-level medicines are available at the other service levels. Additional medicines included on the therapeutic interchange database are the anti-depressants: escitalopram and sertraline (for use if citalopram and/or fluoxetine are unavailable), and the injectable anti-psychotics: haloperidol and clotiapine (for aggressive disruptive behaviour if intra-muscular or oro-dispersible formulations of olanzapine are unavailable).

Apart from the anti-epileptics, all psychotropic medicines in the PHC STG are listed as ‘doctor-prescribed’ as there are currently no other authorised prescribers of these medicines. Tertiary and quaternary medicines are specialist-prescribed, related to the clinically complex indications for these medications. A stepped-care approach is used, with non-specific general measures followed by medicine treatment, and recommendation for referral if there is a poor response to treatment or indications of severity. However, only the bipolar disorder algorithms in the adult hospital STG include a management goal and suggested rating scales for assessing treatment response. In addition to referral recommendations, engagement with specialist services throughout the care trajectory is recommended for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in adults, related to the complexity of the conditions rather than to the potential dangers of the medicines.

Except for sedation of an acutely disturbed child, mental health care of children and adolescents is restricted to hospitals. With the exception of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) which has detailed guidelines aimed at medical officers, management in consultation with a psychiatrist is generally recommended. Psychiatric referral is recommended for all children and adolescents with bipolar, psychotic, or eating disorders, children under 12 years old with depressive, generalised anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders, and children younger than six years old with symptoms of ADHD.

Non-pharmacological interventions, including psychotherapy and occupational therapy, where available, and use of psychosocial services in the non-health or non-governmental sectors are encouraged in all the guidelines of the STG. Brief descriptions of psycho-education and risk assessment are provided in the PHC and adult hospital STG, and the PHC STG include sections on general monitoring and care of people with mental illness, suicide risk assessment, and special population groups.

Analysis of medicine procurement data

The medicines included in the analysis are listed in Table 2, together with their DDD and cost per DDD. Apart from long-acting methylphenidate, the cost per DDD was calculated from 2023 tender prices and averaged over medicine strengths and pack sizes procured.

The tricyclic anti-depressant amitriptyline, anti-epileptic medicines and benzodiazepines were excluded from this analysis, as they are also recommended in the STG for use in non-mental health conditions, including neuropathic pain, epilepsy, and procedural sedation, respectively. Bupropion was not included in the analysis, as it was not on national tender during the period under study due to venlafaxine being more affordable. Intramuscular (IM) haloperidol was also not included, as the product registered in South Africa is no longer marketed here. While IM clotiapine was procured instead of IM haloperidol for the study period, the IM and oro-dispersible formulations of olanzapine were not readily available, as they were added to the EML only in 2024.

In 2023, almost R290 million was spent on the included medicines (Table 2). The most expensive medicines were the injectable anti-psychotics used in the acute management of aggressive disruptive behaviour (clotiapine IM and zuclopenthixol acetate IM). However, greater expenditure is incurred with chronic medicines, and the cumulative budgetary impact of small differences in cost per DDD may hinder population coverage and sustainability. Because of the unaffordability of long-acting methylphenidate tablets compared to the short-acting methylphenidate, the former are not on the EML. However, they were on national tender from 2019 to 2021 and therefore were included in the analysis.

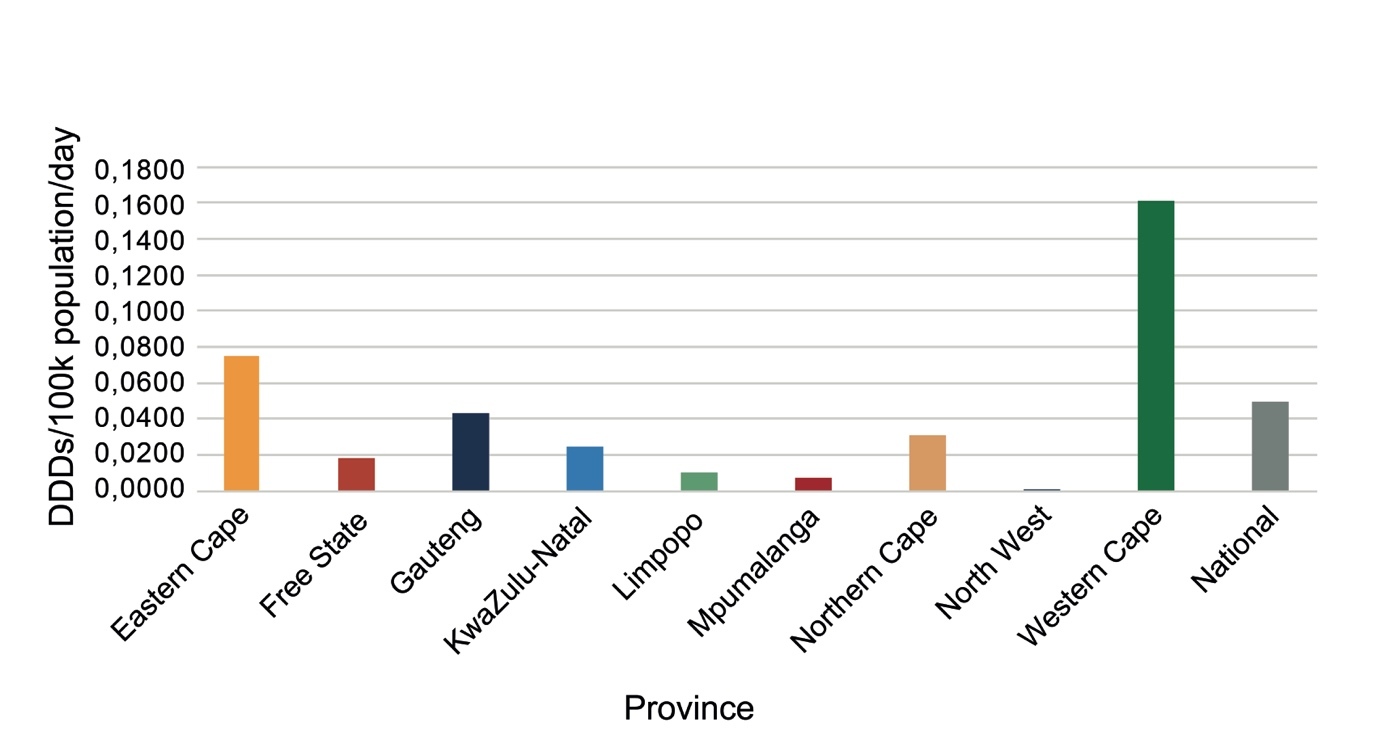

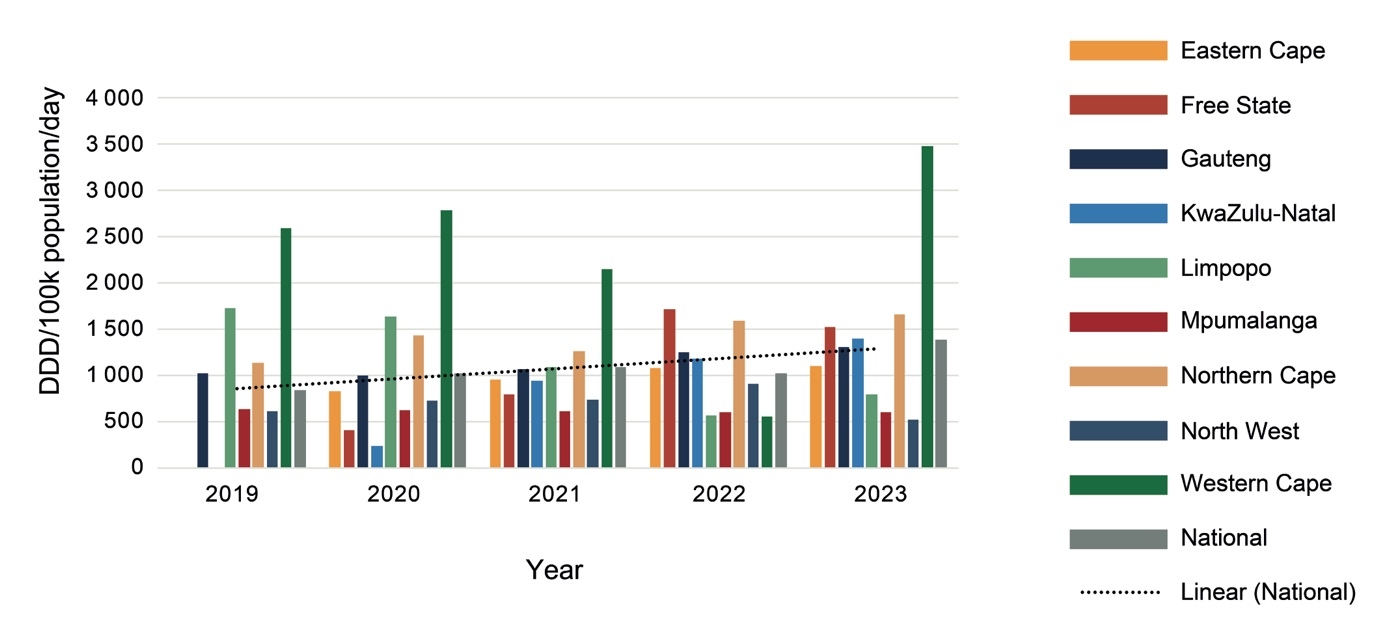

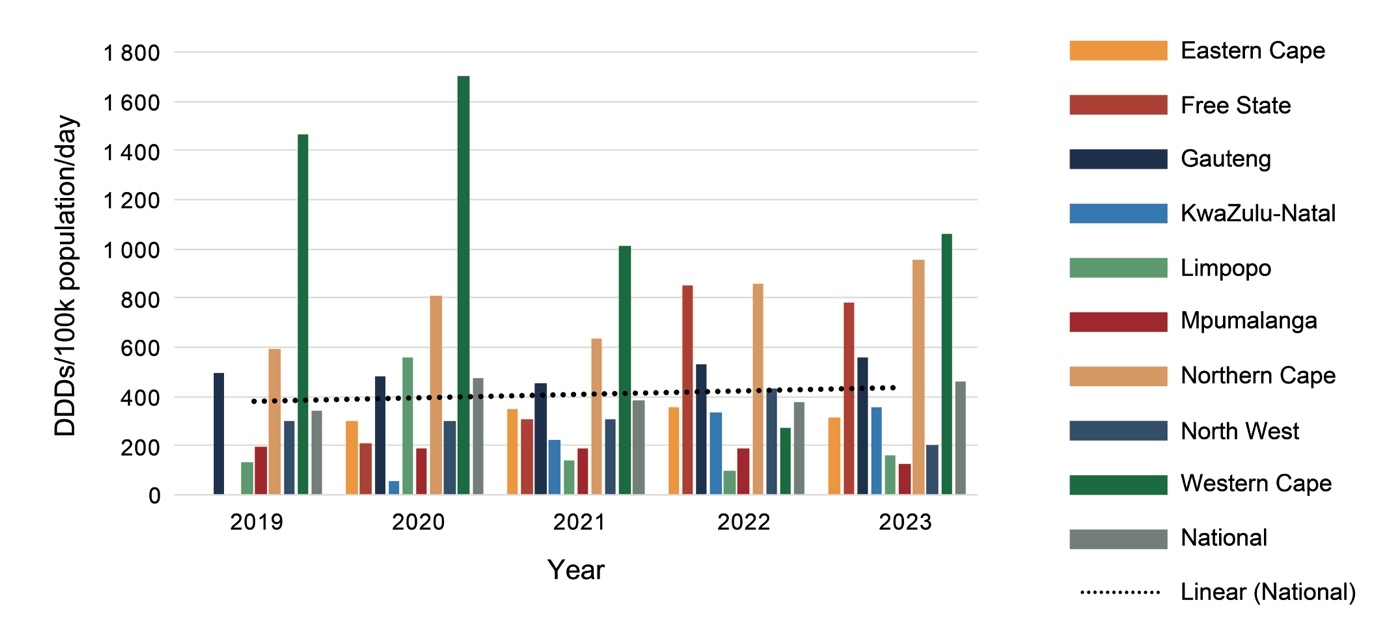

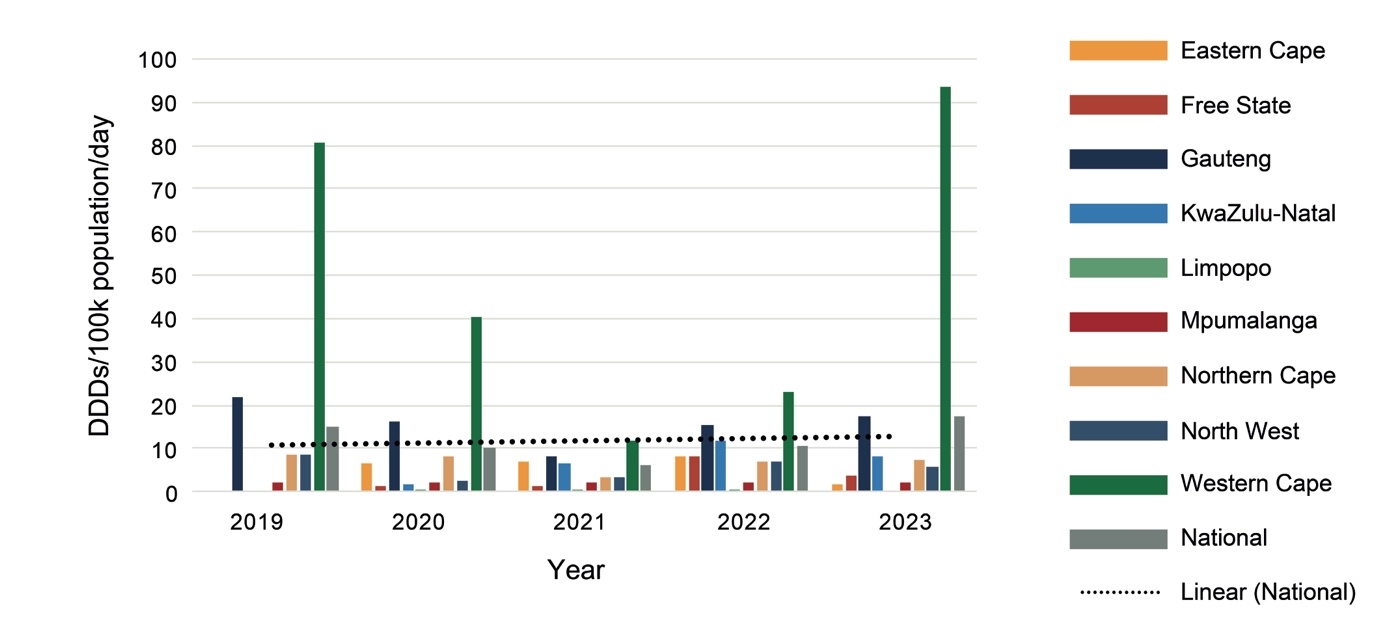

Expenditure on psychotropic medicines by each province per 100 000 uninsured population varied considerably, with the Western Cape spending the most and Mpumalanga the least (Figure 1).

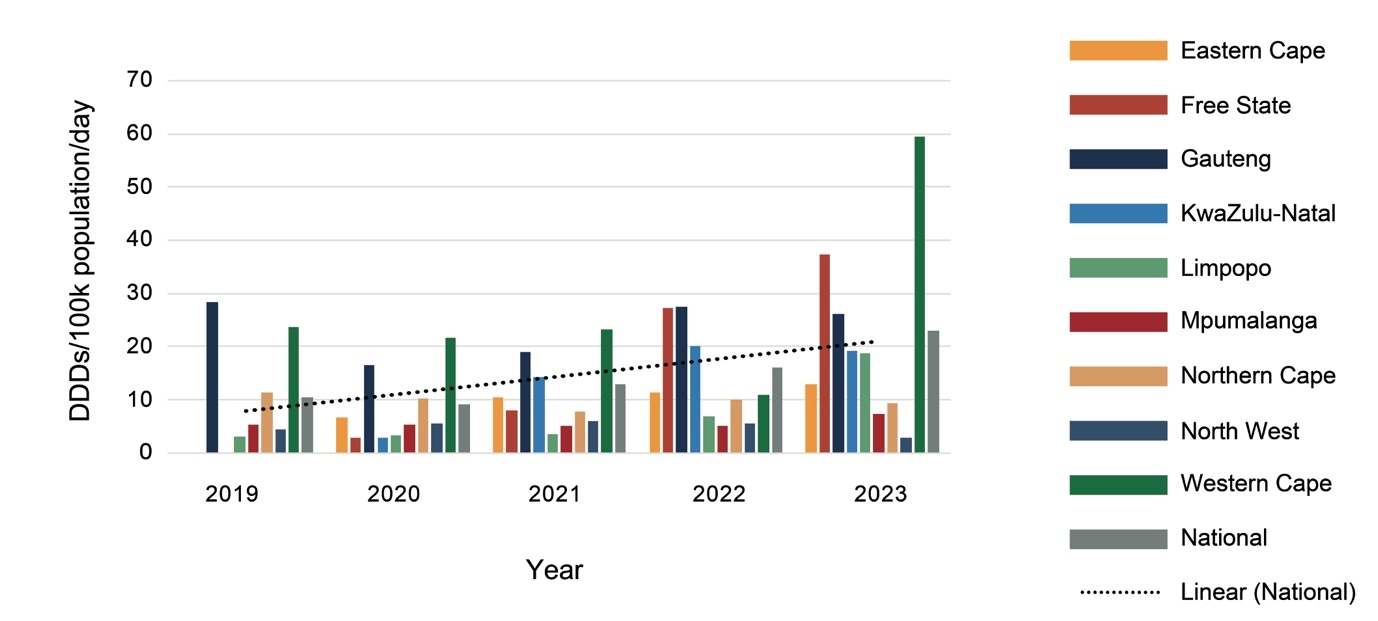

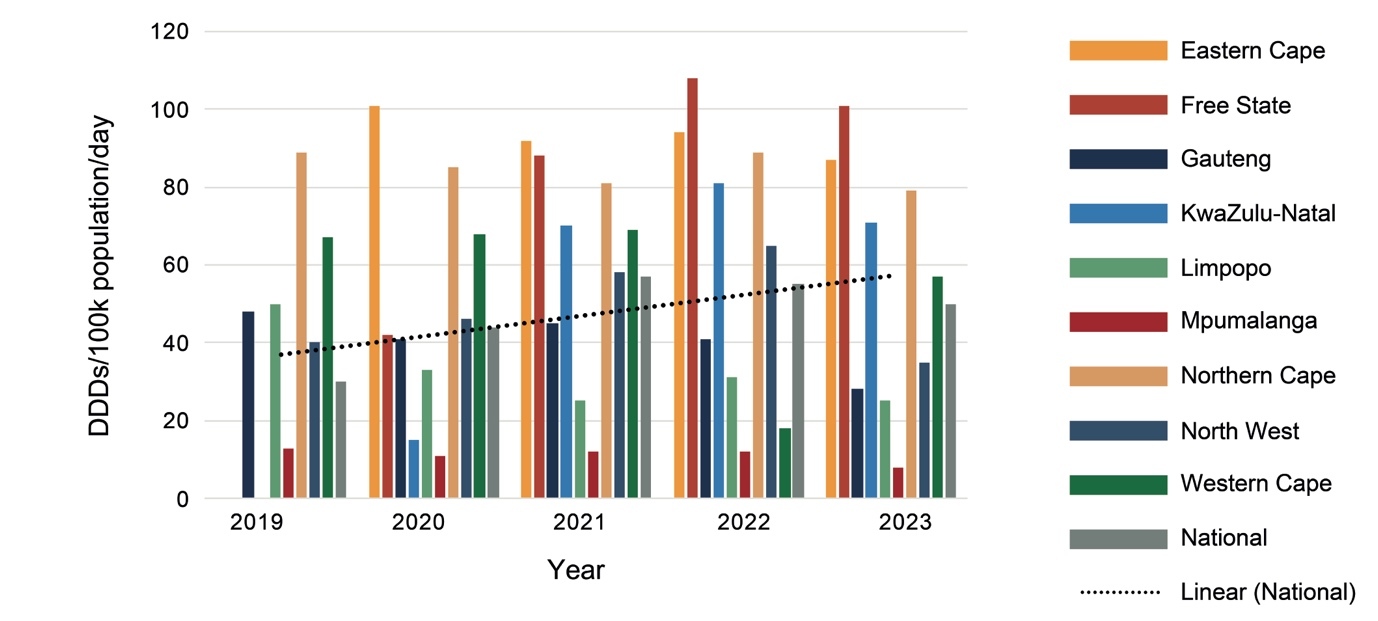

As shown in Figure 2, procurement increased nationally by 66% from 2019 to 2023, with marked variations between provinces and from year to year. Much of this increase is due to a 35% increase in procurement of psychotropic medicines by the Western Cape between 2019 and 2023, and the Eastern Cape, Free State and KwaZulu-Natal Provinces changing from provincial to national procurement processes between 2019 and 2020. While KwaZulu-Natal increased procurement each year, Limpopo Province had a general decline in procurement, and Mpumalanga had almost no change.

There was little change in procurement of anti-depressants over the five years (Figures 3 and 4). Provinces showed different patterns of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) procurement, with fluoxetine favoured by the Eastern Cape, Free State, Mpumalanga (which did not procure citalopram at all), Northern Cape, North West, and Western Cape. While KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo Provinces procured similar quantities of both SSRIs, and Gauteng procured more citalopram. Venlafaxine was procured in much smaller quantities than the SSRIs, mostly by the Western Cape and not at all by Limpopo Province.

In 2023, 475 DDDs of antidepressants were procured per 100 000 uninsured population per day, meaning that just under 0.5% of the uninsured population could have accessed medicine treatment for depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder if each person was prescribed one of the three anti-depressants at the DDD for the year.

As with anti-depressants, procurement patterns for anti-psychotics differed between provinces (Figures 5 to 8). Procurement of anti-psychotics used in maintenance treatment (Figures 5 to 7) increased over the five years, with increases of almost 40% for oral first-generation anti-psychotics (FGAs), 66% for long-acting injectable FGAs, and 240% for second-generation anti-psychotics (SGAs). In 2023, oral SGAs were the most used anti-psychotics, with procurement of almost 400 DDDs per 100 000 uninsured population per day.

While oral haloperidol was the most procured FGA by all provinces each year, procurement of SGAs varied. Risperidone was the most procured by each province between 2019 and 2022, followed by olanzapine in all provinces except for the Free State and Limpopo (which procured more clozapine than olanzapine) and Mpumalanga (which did not procure any olanzapine at all). However, an increase in amisulpride procurement was notable in 2023, especially by the Eastern Cape, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape Provinces, so that it became the most procured item that year nationally, followed by risperidone at 171 and 113 DDDs per 100 000 population per day, respectively.

Procurement of IM anti-psychotics used in the emergency setting (Figure 8) almost doubled over the five years, with the Western Cape procuring the least, suggesting that there are fewer emergency psychiatric admissions there than in other provinces. However, it is not known whether provinces purchased haloperidol IM from outside South Africa using a section 21 application, or purchased an alternative IM anti-psychotic that is not included on the EML on quotation, as these data are not collected by the National Surveillance Centre.

Due to supplier constraints, lithium was supplied via the national tender only in 2023, resulting in national procurement data being available only for that year (Figure 9). As with the other psychotropic medicines, there are marked disparities between provinces, with the Western Cape and North West procuring the most and least, respectively.

Methylphenidate procurement, illustrated in Figure 10, includes the procurement of short- and long-acting tablets for 2019 to 2021, but only short-acting tablets in 2022 and 2023. As only NSC data were analysed, additional procurement of long-acting methylphenidate at a local level during the last two years is not represented in the graph.

The number of DDDs procured per 100 000 uninsured population per day increased by 130% over the five years, with steady increases in the Eastern Cape, Free State and Limpopo. However, only 23 DDDs per 100 000 population per day were procured in 2023 ─ enough to treat 0.023% of the uninsured population for ADHD at 30mg of methylphenidate a day.

Discussion

This review of psychotropic medicine access and procurement in South Africa found that over 25 medicines are on the EML for national use. In addition, guidance on medicine usage and the treatment of mental health conditions has been integrated into the PHC, adult hospital, and paediatric hospital STGs, with some discrepancies between service levels. Of concern, however, is the very low procurement of psychotropic medicines in general, and the marked procurement differences between provinces.

Population coverage

Citing 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study prevalence estimates, the NMHPFSP states that just under 16% of the South African population has a mental or substance-use disorder in 12 months.2 The 12-month prevalence rates of the conditions covered by the STG and EML are 3.8% for anxiety (including PTSD), 3.9% for depression, 0.6% for bipolar disorder, 0.2% for schizophrenia, 1.2% for ADHD, and 1.6% for alcohol, and 0.7% for drug use disorders. While disorders such as intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder do not require medication, people with these disorders often have comorbid mental disorders which require medication; it is not known whether such comorbidities have been adequately captured in prevalence studies.

In 2019, the mental health treatment gap for the South African population dependent on the public health sector was estimated at more than 90%, based on the prevalence rates, a 2016/2017 financial year national mental health costing survey, and District Health Information System data.13 This is somewhat higher than the often-reported 75% treatment gap estimated by the South African Stress and Health (SASH) study.14 The 2019 estimate was calculated using service-related data for the uninsured population only, whereas the SASH study (which evaluated only anxiety, and depressive and substance-use disorders in adults) was derived from a 2004 investigator-administered diagnostic questionnaire-based survey of a nationally representative sample population, some of whom would have accessed private healthcare services. However, the different estimates could represent a widened treatment gap over the 15 years between the two studies. As a reflection of medicine utilisation, this medicine procurement analysis provides some insight regarding coverage, although higher utilisation may reflect increased dosages and/or poly-pharmacy.

Anti-depressant utilisation

For 2023, sufficient anti-depressants were procured to treat 0.5% of the population with a single medicine at the DDD for anxiety, and depressive and stress-related disorders. Using a combined prevalence of 7.7%, this indicates a 93.5% treatment gap for anxiety and depressive disorders. Although not everyone with anxiety and depressive disorders requires medication, and comorbidity may cause duplication of cases, the prevalence rates cited by the NMHPFSP are lower than those found in the SASH study (8.1% and 4.9% for anxiety and depression, respectively), suggesting that this study’s estimate is not unrealistic.

Anti-psychotic utilisation

Anti-psychotics accounted for most psychotropic medicine procurement and increased substantially over the five years, especially for SGAs. While increased anti-psychotic utilisation in South Africa may indicate greater coverage of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, further research is needed. The increasing burden of substance use,2 particularly of substances such as methamphetamine that may induce psychotic disorders, could be at least partially responsible for the increased anti-psychotic utilisation. Furthermore, in African countries, prescribing two or more anti-psychotics (usually an oral SGA in combination with a long-acting injectable FGA) has been noted in 40% of people with schizophrenia, often in males with repeated hospitalisations and comorbid substance-use.15

Methylphenidate utilisation

ADHD in children and adolescents is the only indication for methylphenidate in the STG, and the increased procurement may well indicate increased coverage. However, at the population prevalence for ADHD of 1.2% cited by the NMHPFSP, potential coverage of 0.023% leaves a 98% treatment gap. Even with additional local procurement of long-acting methylphenidate, coverage is markedly inadequate, as the prevalence of 1.2% is probably an under-estimation; globally, ADHD occurs in 5 to 6% of youth with little variation between countries, and in approximately 2.5% of adults.16

This low coverage is very concerning. Methylphenidate improves sustained attention and reduces impulsivity, which negatively affects behaviour. Observational studies, mostly from Taiwan and Scandinavia, indicate that compared to untreated ADHD or periods without medication, stimulant treatment is associated with reduced criminal behaviour and fewer accidental injuries, burns, substance use, sexually transmitted diseases, teenage pregnancy, and suicide attempts.16 Importantly, positive behavioural associations with methylphenidate appear to be greatest if treatment is sustained. However, achieving wide coverage and consistent treatment may be unaffordable for South Africa, related to both medicine costs and accessible clinical expertise.

Provincial differences in access

Provinces differed from each other considerably in expenditure on psychotropic medicines (Figure 1) and number of DDDs procured (Figure 2), with the Western Cape, followed by the Northern Cape, procuring the most DDDs per day per 100 000 population, and North West followed by Mpumalanga procuring the least in 2023. The Northern Cape procured more DDDs with less expenditure than the Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, indicating greater usage of cheaper medications. Provinces estimate their medicine requirements based on historical procurement figures rather than epidemiological data, and therefore the quantities procured tend to reflect past usage rather than clinical need.

Assuming that there is little variation in prevalence of mental health conditions between provinces, inter-provincial disparities in medicine procurement probably reflect differences in access to care as well as prescribing practice. The Medicines Act necessitates access to a psychiatrist for maintenance treatment of persistent conditions (e.g. for relapse prevention in severe depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, or for long-term control of symptoms in severe anxiety disorders and in ADHD). Consistent with the legislation and the clinical complexity of these conditions, the STG recommend that patients should be managed long-term in consultation with a psychiatrist. In the STG, all psychotropic medicines may be prescribed by any registered medical practitioner except for amisulpride, aripiprazole and venlafaxine, which are restricted to tertiary and quaternary care as a means of ensuring specialist assessment and cost-containment.

However, having more psychiatrists does not necessarily mean more medicine procurement. The finding that the Western Cape procured the most psychotropic medicines is consistent with the finding by Docrat, et al.13 of the Western Cape having the most psychiatrists (0.89 per 100 000 uninsured population). However, compared to Gauteng Province, the Northern Cape procured more and KwaZulu-Natal procured similar medicine quantities with far fewer psychiatrists (0.51 versus 0.40 and 0.12 per 100 000 uninsured population in Gauteng, Northern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, respectively). Thus, the efficiency of each provincial mental healthcare system should be evaluated. Of note is that the Northern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal Provinces, having more medical officers than Gauteng, may be relying on this staff cadre to provide mental health care. In addition, KwaZulu-Natal has developed a telepsychiatry system to facilitate remote specialist supervision.17 In Gauteng, an analysis of psychotropic medicine procurement for the 2017/18 financial year found that 60% of DDDs were procured for use in the PHC setting (where care is provided by community psychiatric teams as well as PHC practitioners) and only 25% by tertiary, central and specialised hospitals, which have a greater number of psychiatrists.18

Without treatment outcome measures, this analysis cannot provide insight regarding which provinces offer the best quality of care. National mental health indicators provide little insight into the quality of care provided by the different provinces, with only the recently added suicide attempt rate reflecting a person-centred outcome.2 Importantly, the MHCA promotes community-based care, close to the person’s home and integrated into general health services. However, the rapid de-institutionalisation which followed the promulgation of the MHCA in South Africa has led to high levels of homelessness, incarceration, and repeated hospitalisations among people with severe mental disorders.2 Such individuals must have access to psychotropic medicines after hospital discharge, as well as psychosocial and community support.

While the NMHPFSP recommends a task-shifting approach that enables primary, secondary and tertiary preventative and recovery-orientated mental health care, it also cites staffing norms for specialist-level community mental health professionals. A community-based mix of healthcare providers is consistent with global experience of factors facilitating successful de-institutionalisation.3 Such a workforce should also improve access to care for people with depression, anxiety, PTSD and ADHD, who do not require hospitalisation but would benefit from collaborative specialist input. Nevertheless, a marked shortage of medical practitioners is the reality for most of South Africa, particularly in PHC settings that rely heavily on nurse-prescribing19 which is currently limited to Schedule 4 medicines.

Limitations

This policy review included only STGs developed in line with the National Drug Policy and not clinical programme guidelines. However, medicines included in clinical programme guidelines should be aligned with the STG. The reliance on procurement data is a limitation, as some procurement may be followed by diversion, theft or inappropriate use. Procurement data could also not be corrected for periods of restricted supply or stock-outs. Nevertheless, relying on procurement data as an approximation of utilisation, and therefore service delivery, is defensible.

Recommendations

Based on the analysis presented in this chapter, the following recommendations are offered:

-

Workforce needs and training gaps in each province should be clarified, with appropriate multi-disciplinary personnel and task-shifting, and adequate specialist and sub-specialist support to enable comprehensive community-based care and safe discharge of people with mental disorders from tertiary to district services, as envisaged by the MHCA.

-

Urgent attention to current legislative restrictions on mental health service provision by appropriately trained nursing personnel is needed by addressing the creation of appropriate specialist nurse qualifications and registers, and/or rescheduling of selected medicines.

-

Coverage targets, linked to the available financial resources, with tracking of expenditure against a mental healthcare-specific budget, should be established.

-

Urgent revision of the mental healthcare indicators in the National Indicator Data Set is required, incorporating targets (such as coverage) and outcome measures (such as re-admission rates) in routine monitoring systems.

-

Patient-linked data with reliable coding of clinical diagnoses are needed. As electronic records are implemented, the creation and maintenance of registers for people with specific mental health care conditions should be prioritised.

-

Well-designed and executed observational studies, focused on meaningful outcome measures, should be conducted.

-

As universal health coverage is expanded, consideration should be given to the development of new models of reimbursement, enabling collaboration between disciplines and mobilisation of the entire mental healthcare service capacity of the country, for the benefit of all who reside in South Africa.

Conclusion

Existing medicine policy and STGs support the provision of effective mental health care with a range of psychotropic medicines at all service levels. However, the analysis of procurement data over time indicates inadequate population coverage as well as inequity between provinces in access to care. Effective community-based mental health care services depend on an accessible, appropriately trained health workforce. Measurable, person-centred outcome indicators are needed to assess whether the goals of treatment are achieved.

_procurement_between_.jpeg)

_procurement_betwee.jpeg)

_procurement_between_.jpeg)

_procurement_betwee.jpeg)