Introduction

In its three decades of democracy, South Africa’s mental health system has seen considerable change. Importantly, mental health has been included in several key policy and legislative reforms, particularly its integration into the broader health system.1–7 Despite progress in instituting integration, de-institutionalisation and decentralisation through these instruments ─ notably through the introduction of the Mental Health Act (17 of 2002)8 and two successive National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan (NMHPFSP)9,10 iterations ─ substantial gaps remain in the implementation of person-centred, comprehensive, integrated, and human rights and equity-based mental health services to the population. Specifically, funding and resource availability continues to be heavily concentrated at specialist and hospital levels of care, and substantially skewed towards urban areas; integration at the Primary Health Care (PHC) level remains limited; structured community mental health services are rare, apart from single urban pockets throughout the country; standards of care during and after institutionalisation are woefully inadequate, and strong intersectoral governance and strategic budgeting are absent.10–12

Much has been published on the history of South Africa’s mental health system and its policy and system reforms from its colonial past to the post-democratic era.5,6,13,14 South Africa’s journey from a colonial, apartheid-driven mental health system to one that is democratically rooted has been summarised in two important reviews, namely a 2000 publication by Thom,13 and a 2011 publication by Petersen and Lund,4 the latter building on the initiative of the former. These two papers reflect key global and local movements in the mental health systems reform trajectory which foregrounds rights-based approaches and person-centred care.

From 2011 to the present, substantial global and local changes have occurred in mental health system reforms, including the continuation of the Movement for Global Mental Health and its substantial funding advocacy,15 which in turn has led to an improved climate for the implementation of several key research programmes in South Africa. During this period, South Africa also launched its first formal mental health policy, the National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan (NMHPFSP) 2013─2020,9 as well as its continuation in the 2023─2030 period.10 There has also been a gradual recognition of the importance of investing in initiatives that will bring South Africa closer to the Sustainable Development Goals 2030,16 under the National Development Plan 2030.17 Furthermore, National Health Insurance (NHI) has been formally introduced through legislation and policy, boosted by several policy changes meant to strengthen the health system in preparation for its roll-out, such as PHC re-engineering and hospital revitalisation.18,19 Limitations in progress towards mental health system goals were laid bare in the Life Esidimeni events; the reporting and subsequent investigations severely underlined systemic failures in strategic objectives such as decentralisation, governance and leadership, strengthened community-based services, intersectoral co-ordination, and human rights-based care.20–23 Subsequently, the underinvestment in community-based care and need for overall increased investment in mental health care has been highlighted.11 Finally, disease patterns have changed in important ways since 2011, with a substantial rise in South Africa’s non-communicable disease burden on the one hand, and the COVID-19 pandemic shock on the other, both highlighting the urgent need to integrate mental health and other programmes into a person-centred service approach, particularly at PHC level.24

Given these developments, revisiting the path set by Thom,13 Petersen and Lund4 is timely. This study presents a current review of South Africa’s mental healthcare research and system progress, by: (1) mapping out the type, scope and focus of research studies that have been undertaken, and (2) drawing conclusions from those studies on the progress made towards reforms in developing a people-centred mental health system. Accordingly, an integrative review was undertaken to systematically identify and synthesise published empirical evidence in public mental health care in South Africa, from 2011 to 2024.

To guide the review, the objectives of the World Health Organization (WHO) framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services (IPCHS)25 were used. The framework outlines five broad areas for delivering people-centred services, namely: (1) engaging and empowering people and communities; (2) strengthening governance and accountability; (3) re-orientating the model of care; (4) co-ordinating services within and across sectors, and (5) creating an enabling environment. The framework provides both a guideline for re-orientation of health services for health systems strengthening, and a means of evaluating service improvement, making it appropriate for the aims of the current review.

Method

An integrative review26 of empirical, published research focusing on development and implementation of public mental healthcare services in South Africa from 2011 to 2024 was undertaken. This allowed for the inclusion of both experimental and non-experimental research. Accordingly, the following steps were pursued26:

Problem identification

Key search questions were refined in discussions between the authors and an expert oversight group comprising senior researchers in mental health in South Africa. Accordingly, the research questions were as follows:

-

In terms of type, scope and focus, what public mental health service research has been conducted in South Africa between 2011 and 2024?

-

In step with IPCHS, what lessons and recommendations can be gleaned from this literature in terms of South Africa’s mental health system reform objectives?

Literature search

A search strategy was developed based on the key questions identified. Database-specific search syntaxes were developed following best practice guidelines.26 A trained research assistant undertook searches in EBSCOhost (including Medline, Healthinfo, Sabinet), PubMed, and Google Scholar, for the period November 2010 to September 2024, using the following key phrases:

(‘mental health services’ OR ‘mental healthcare’ OR ‘psychiatric services’ OR ‘behavioural health services’) AND (‘community health services’ OR ‘primary health care’ OR ‘secondary care’ OR ‘tertiary care’ OR ‘mental health systems’ OR ‘health services’) AND (‘research’ OR ‘evaluation’ OR ‘assessment’ OR ‘progress’ OR ‘impact’ OR ‘outcome’ OR ‘effectiveness’ OR ‘service delivery’) AND (‘South Africa’ OR ‘South African’).

Data evaluation

Results were screened for inclusion based on containing data relevant to the study and being of sufficient quality. A total of 1 869 papers were included for title screening following an application of the search parameters, of which 218 remained after title screening.

Abstract screening was conducted using Covidence by the two authors and a research assistant (each abstract being reviewed by two researchers), resulting in 135 included abstracts. Full texts of included abstracts were reviewed for inclusion (each by one author), resulting in 126 papers for final analysis.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from full texts by the two authors and a research assistant. NVivo 15 was used to store and manage the data.

Data analysis

The data were analysed thematically in NVivo 15 using the WHO framework on IPCHS.25 An initial coding framework was developed based on the five areas for delivering people-centred services of the WHO framework. For each of these framework components, themes were developed including the progress made, and barriers hampering progress towards objectives were reported in terms of the findings of the included studies, where data were available. Recommendations (potential enablers) were then made on the basis of addressing these barriers.

Presentation

The findings are presented in narrative form, structured to answer the research questions of the review.

Findings

Overview of mental healthcare research published between 2011 and 2024

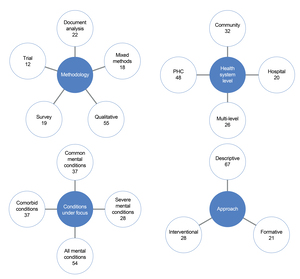

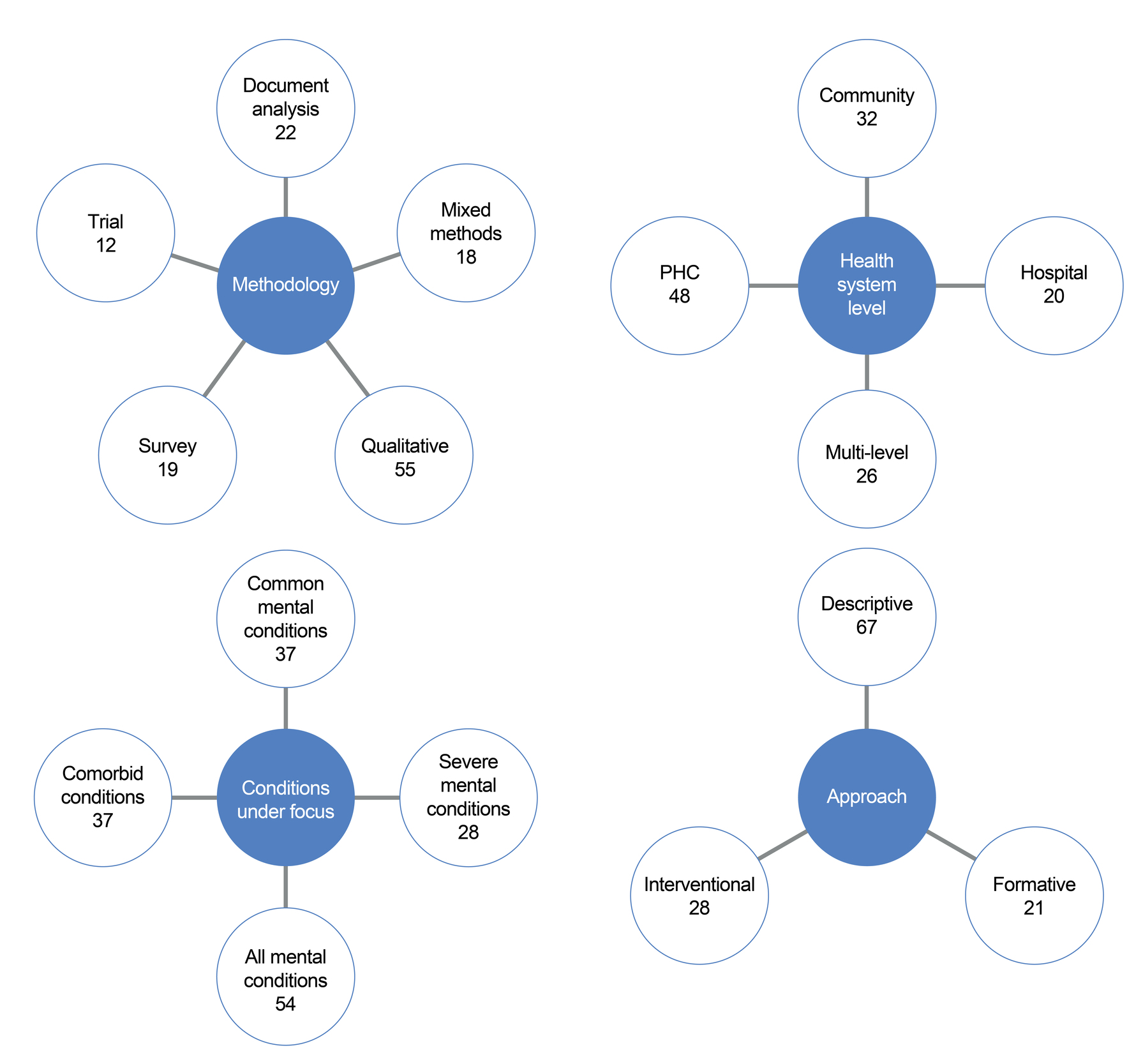

A total of 126 papers over the period of 13 years were included for final analysis (Table 1). As depicted in Figure 1, the bulk of papers used qualitative methodologies (n = 55), followed by document analysis (n = 22), surveys (n = 19), mixed methods (n = 18), and trial studies (n = 12). In terms of health-system level, 48 papers focused on PHC, followed by 32 at community level, with fewer studies with a multi-level focus (n = 26) and hospital focus (n = 20). A relatively large proportion of papers focused on non-specified mental health conditions (mental health care in general; n = 54), followed by common mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (n = 37), severe mental health conditions (n = 28), and comorbid conditions (n=7) as focus. A substantial proportion (n = 67) of the included studies were descriptive in nature (e.g. describing challenges, bottlenecks, and experiences related to mental health system structures and processes). Smaller proportions of the included studies featured the description, implementation and/or evaluation of intervention programmes (n = 38), with fewer involving formative research towards informing the development of interventions (n = 21).

Mental health system people-centredness

Empowering and engaging people

In terms of the WHO IPCHS framework, empowering and engaging people involves “care that is delivered in an equal and reciprocal relationship between, on the one hand, clinical and non-clinical professionals and, on the other, the individuals using care services, their families, and communities, thereby improving their care experience.”25(p5) Progress in this area was noted as encompassing provision of opportunities, skills and resources towards unlocking individual and community resources for action, as well as reaching the underserved and marginalised.18 The role of self-help organisations and targeted support for families were highlighted as an important element in empowerment processes.38,98,146 While the bulk of research undertaken involves conventional research designs, recently, more participatory approaches have been adopted, such as human-centred design82 and learning health systems.147,148 Policy participation by mental health service users is suboptimal, and their confidence for participating in such processes can be marred by stigma and discrimination.35 Furthermore, stigma remains a pressing barrier in terms of mental healthcare provision in general, and in relation to implementing family interventions and developing interventions for specific high-risk groups such as survivors of domestic violence.42,44,47,51,53,73

Another barrier halting progress towards empowerment is that some groups, such as adolescents and adolescent mothers,148,149 prisoners,81 and young women,88 are harder to reach. It was highlighted by one study that, particularly regarding vulnerable groups such as survivors of gender-based violence, intervention implementers should share backgrounds and communities with the service user.32 Within South Africa’s multi-lingual context, a similar and particularly problematic barrier to care was the inadequacy of interpretative services during consultations; many African languages provide different interpretations of the meaning of mental health phenomena.140,147,148 Childhood and parenthood were identified as crucial periods, where stigma, family stability and low-income status substantially influenced the uptake of psychological interventions in the household.46,104

Strengthening governance and accountability

Strengthening governance and accountability involves promoting decision-making transparency and the development of systems for collective accountability of health providers and managers.25 This theme had very little evidence showing progress among the papers analysed. In terms of service user participation in service and policy design, there is evidence of an acknowledgement that people with lived experience of mental health conditions should play a meaningful role in co-production of services, although some doubt their inherent capacity to express their needs and felt that caregivers would be better suited to this endeavour.44 Another paper noted that “The importance of modifying system-strengthening interventions to suit varying contexts in pragmatic trials that span more than one district is highlighted; as is key stakeholder involvement in co-designing district-specific implementation strategies to support implementation.”27(p11) Accountability and decision-making transparency were not covered in the included studies, nor were specific barriers to progress in this area identified, indicating that this may be an important area for future investigations.

Re-orientating the model of care

Re-orientating the model of care requires shifts towards prioritising primary and community care services, moving from in-patient to out-patient and ambulatory care, and the co-production of health. This entails investment in health promotion and ill-health prevention strategies, inter-sectoral collaboration, as well as best use of scarce resources.25 Progress under this objective emerged as evidence of the development of tailored approaches for crucial mental health considerations across the life course. These included programmes for women’s mental health promotion across pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum, requiring shifts in practice and support across these different stages in order to ensure better mental health.31,73 Similarly, adolescence is increasingly being recognised as a critical period for intervention, with initiatives such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for improving post-traumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms among adolescents emerging.65

Specific evidence of progress towards re-orientation of services to community mental health was presented in an audit of community mental health services in Southern Gauteng, which described how services were provided through District Health Services through the PHC budget. This included out-patient services at PHC clinics, residential and day care facilities, and psycho-pharmaceutical support by psychiatric registrars and medical officers under supervision. Psychologists provided therapeutic services, but assertive, active follow-up services were lacking.56 In terms of mental health care for children and adolescents, service users could, depending on the context, access care at a PHC clinic or at hospital level, via a specific healthcare worker (public or private), or through traditional health practitioners or faith-based services.60 Beyond services at the PHC and hospital levels, smaller-scale initiatives were described in some settings as providing services at community level, particularly for people living with severe mental conditions. These include clinical community psychiatric teams,128 assertive community treatment (ACT),142 caregiver-orientated mental health services in rural areas,108 and the inclusion of occupational therapists in day care for service users.120 Some progress has also been made in providing recovery and psychosocial rehabilitation services for service users who mostly receive clinical recovery services with very limited psychosocial support. This included self-organising, caregiver support, task-shared psychosocial support services, and step-down and day care facilities.75,105,115,116,119,121

Progress in integration of mental health services within PHC clinics has also been receiving attention in several sites.49,52,63,80,89,97,124,145 Garnering the support of district and facility health managers has been identified as key to research in re-orientating the model of care.125 Some work has focused on programmatic integration of mental health with other programmes such as tuberculosis and maternal-child healthcare,94 HIV and diabetes care,87 and general chronic illness care.27,89,90,108,125,145

Models of integrated mental healthcare using task-sharing at PHC clinic level showed promise in KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape. In KwaZulu-Natal, this involved a collaborative care model built on continuous quality improvement and health system strengthening for sustainable implementation, utilising task-shared screening and counselling within improved screening and referral practices.54,126 While shifts to care at PHC and community health levels are vital to creating a more people-centred system of care, this often means that demand for services is elevated which, in turn, rapidly outstrips supply. In the KwaZulu-Natal mental health integration into primary care (MhINT) programme, screening at community and PHC levels were implemented with a co-developed referral pathway, embedded in the Ideal Clinic framework and the integrated clinical services management model of managed care for chronic conditions.28,54 In the Western Cape, motivational interviewing and problem-solving therapy delivered by community health workers (CHWs) further highlighted the strength of evidence for the feasibility and effectiveness of task-sharing for common mental conditions at PHC level.40,57,125 Within these initiatives, validated tools were developed to support the integration of mental healthcare within PHC and, through the Ward-based Outreach Teams programme, within community health services, including the Brief Mental Health screening tool150 and the Community Mental Health Education and Detection tool.34,131,138 Further, the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) tool was developed to measure therapeutic aptitudes required for effective psychological intervention, including delivery by non-specialists.68 Given the nature of mental health care, it was noted that service users often require more sessions or more prolonged time with CHWs.55 While the transition to use of digital technologies is likely to be an important marker of progress towards service re-orientation, a limited number of papers in this review focused on the incorporation of digital technologies in delivering mental health services. Those that did included using text messaging to promote treatment adherence and prevent hospital re-admissions among people living with severe mental conditions,45 and a telepsychiatry model developed for supporting mental health services.33 The challenges of COVID-19 underlined the necessity of digital platforms to support services at PHC level, and it was noted that in certain settings, providers applied several innovations to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, including telehealth, online training, online peer support, and online community outreach.83 Regarding barriers to re-orientating the model of care, hospital re-admission following acute psychiatric hospitalisation is a well-known quality indicator of a country’s health system performance at PHC and community levels. In this vein, re-admissions in South Africa remain a substantial challenge, suggesting that psychosocial support structures are missing at the PHC and community levels of care.45,101,151

Co-ordinating services

Co-ordinating services involves the co-ordination of services around people’s needs and preferences at all levels of care, and the integration of service providers and sectors (inter-sectoral collaboration), through harmonising and aligning service processes.25 Some papers described integrating public mental health services with advocacy support from non-government organisations (NGOs) such as the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG), the North Gauteng Mental Health Society (NGMHS), and Families South Africa (FAMSA).87 A pilot study looked at co-ordination between traditional health practitioners and public health service providers in the early identification of psychosis,82 and there have been other efforts to integrate psychiatric services with traditional health practice.53,82

Regarding barriers to coordination of services, poor intersectoral coordination of care continues to be highlighted, particularly in the management of care for people living with severe mental conditions, where there is an identified need for the Health and Social Development sectors to coordinate different services – in addition to better coordination of several different kinds of service providers on community level.42,44,80,105,115,152 More generally, studies highlighted that service coordination is often marred by limited capacity at district administration level,103 stressing the need for investments in administration and management and not only service providers.28

Creating an enabling environment

Creating an enabling environment requires coalescing stakeholders for transformational change in legislative frameworks, financial arrangements and incentives, and the re-orientation of the workforce and public policy-making. This is a particularly important construct in people-centred system reform, as it cuts across the considerations raised thus far. It involves “a diverse set of processes to bring about the necessary changes in leadership and management, information systems, methods to improve quality, re-orientation of the workforce, legislative frameworks, financial arrangements, and incentives”.25(p9) In terms of policy progress in this regard, while South Africa’s NMHPFSP has filled a crucial gap in reforming care, participation in the policy development process and provisions for subsequent implementation were reportedly suboptimal: “Findings revealed that no substantive changes were made to the mental health policy following the consultation summits. There do not seem to have been systematic processes for facilitating and capturing knowledge inputs, or for transferring these inputs between provincial and national levels. There was also no further consultation regarding priorities identified for implementation prior to finalisation of the policy, with participants highlighting concerns about policy implementation at local levels as a result”.93(p1) Some studies did identify enablers of progress in mental health reform, with mutual learning and capacity-building with district management identified as being key to ensuring that integrated mental health care is in step with district variations, and that mental health is prioritised in programmatic planning processes.28 It was also noted that meaningful change can be achieved through the identification and support of leaders and role-models who are passionate about mental health, and who can champion mental health promotion efforts.31 Health facilities with strong management teams who appear to be invested and committed to support staff and mental health service users often have better implementation capability for re-orientated mental health care, better problem-solving abilities, better re-allocation of scarce resources, and provision of more person-centred care.40

The barriers to creating an enabling environment for person-centred mental health care identified included: a perceived lack of leadership support, poor programme co-ordination, and lack of mental health prioritisation as felt by service providers, creating frustration.42,103 Furthermore, poor communication between management and frontline staff impedes mental health policy implementation.49

A lack of resources (particularly in terms of staffing) was identified as the ever-present implementation challenge, with imbalance between provision for mental and physical health programmes, and particularly lean funding for community care for severe mental conditions and for child and adolescent mental health.31,42,44,49,81,103,113,121,153

Regarding reorienting healthcare workers, papers described training and supervision models in service of task-sharing and integrated primary mental healthcare, including an undergraduate clinical associate programme58,66,102; in-service psychiatric training of PHC nurses97; orientation of managers and PHC staff; training and supervision of registered counsellors and community health workers using master trainers and continuous quality improvement24,27,54,126; training community health workers though a community participation approach147; and structured designated and dedicated training of community health workers to deliver psychological interventions on PHC level.57

Several wider barriers to an enabling environment for mental health service access were highlighted. The Mental Health Act (17 of 2002) and NMHPFSP both underscore the need for changes in physical infrastructure in order to facilitate integrated, human rights-driven mental health care, and measures to address the currently inadequate spaces at PHC and hospital levels.40,42,49 Requirements for improvements were also put forward, although implementation of these requirements remains a challenge.37 Barriers in the wider socio-economic environment were identified; poverty and socio-economic deprivation, as drivers of mental distress, were commonly described. This also translated into reduced capacity for transport to health facilities for routine and acute mental healthcare visits, elevating the need for stronger community care. While the role of families and caregivers is vital in the South African context, and the disability grant system provides an essential protective layer against severe poverty, it was also suggested that the grant generates power dynamics within households in terms of access to monthly payments. Broader South African forces such as labour migration, gender roles, and AIDS-related orphanhood over generations further exacerbate mental health and service access.39,42,44,46,47,70,79,146 In addition to stigmatising attitudes and behaviours towards people living with mental conditions,40,100 some HCWs do not adequately emphasise the connections between mental distress and factors such as gender-based violence, food insecurity, and lack of basic resources.30,31,44 As with all health programmes, mental health care was severely impeded by COVID-19, and some papers described these impacts. COVID-19 and its associated lockdowns resulted in increases in acute psychiatric hospital admissions and out-patient consultation rates, as well as in alcohol withdrawal care rates; reduced service access; disruptions in therapies and medication; increased service burden and stress among HCWs, and reduced service quality and privacy.83,106,135

Discussion

This integrative review was designed to present a current overview of South Africa’s mental healthcare research landscape and how this research illustrates progress made in South Africa’s mental health system reforms. Drawing from publications from the past 13 years, the review highlights some progress as well as persistent challenges in realising people-centred, integrated mental health care. Despite laudable advances in research on the development of health system innovations across hospital, PHC and community levels, as well as some evidence in implementing and scaling-up these innovations in real-life settings, much in terms of system reform has remained strikingly stagnant since Petersen and Lund’s 2011 review.4 Similar to the Petersen and Lund review, this review suggests a dearth of intervention and economic evaluation studies, with most studies being descriptive and formative.

In terms of progress towards developing a more people-centred mental health system, the IPCHS25 was a useful guide for gauging the extent to which the published literature illustrates elements of people-centred care. In terms of empowering and engaging people, it emerged that specific groups of people – such as adolescents, young women and mothers, and prisoners ─ remain hard to reach, both in terms of service provisioning and policy involvement, in part because of stigma. Regarding strengthening governance and accountability, little evidence relating to accountability and decision-making transparency was found. This is certainly not a finding that is unique to mental health care, but reflects a relative lack of research on the topic in health systems research more generally.154 In terms of re-orientating the model of care, the review identified programmes that address critical periods of the life course, including: women’s mental health promotion; adolescence, and service re-orientation towards more community-focused care (including a district initiative in Gauteng).56 Intervention programmes aiming to promote community-based care included outreach by mental health professionals,128,134,142 while various recovery and psychosocial rehabilitation initiatives were described.75,105,115,116,119,121

In step with global trends and recommendations,15,155,156 several programmes were launched to strengthen the integration of mental health into PHC settings.49,52,57,63,80,89,90,97,108,124,125,145 Apart from the Southern African Consortium of Mental Health Integration126 example, rigorous examples of scaling-up evidence-based PHC integration models into district health services were largely absent.

Co-ordinating services included collaboration between government and NGO services and advocacy, as well as with traditional health practitioners who are regarded as playing a crucial role in promoting people-centredness in a mental health system.157

Finally, it is crucial that research and development activities are firmly embedded in an enabling environment. In this regard, strategic management and leadership across all levels of planning and operations are essential for any progress in systems reform, particularly in the contexts of resource disparities and the ongoing need for HCW orientation towards system reform goals such as integrated care and task-sharing. In this vein, the two iterations of the NMHPFSP have been important milestones. While no formal evaluation was undertaken of the NMHPFSP 2013─2020 (and this paper is not intended as an evaluation), it can be inferred that the policy had very limited effects on mental health system reform. Provincial and district-level policy operationalisation of the policy objectives were largely missing, and one analysis suggested that this has been due to poor conceptualisation of processes such as de-institutionalisation in the policy document. The lack of clarity of key directives in the NMHPFSP, as well as logical leaps between the actions and objectives of the policy, has hampered implementation efforts of the policy at provincial and district level.158 The task at hand will entail stakeholder collaborations for mutual learning embedded in strong provincial leadership, in order to identify grassroots issues that can be addressed through low-cost, effective interventions tailored to the wide and multiple variations in population needs and preferences, and system resources in the country. The people-centred principles used as a framework in this paper should be seen as foundational for the eight objectives of the NMHPFSP 2023─2030, as summarised in Box 1.

In terms of Objective 1 (to strengthen district and primary healthcare-based mental health services), there is good-quality evidence of system strengthening using evidence-based innovations. Such examples were found in the Western Cape and in KwaZulu-Natal.40,54,57,107,117,126 In particular, the KwaZulu-Natal MhINT initiative illustrates the importance of strengthening institutional capacity through a learning collaborative, relying on iterative mechanisms of scaling-up intervention components in alignment with available resources through continuous quality improvement.54 With NHI almost certainly being introduced in some form, the development of health facilities that are orientated towards human rights and provide appropriate space for quality services will become ever more pressing; although, despite guidelines having been developed to start some of this work,37 the degree to which such infrastructural revitalisation will be feasible in the current climate of fiscal austerity in public spending is unclear.159 This will also no doubt affect the achievement of Objectives 5 and 7, and as mentioned, the evidence for task-sharing is strong. CHWs, lay health workers, families and caregivers have all been described in the literature to have substantial potential to take on crucial roles in the mental health service continuum, particularly in terms of mental health promotion, education, screening and referral. National guidelines outlining CHW roles and responsibilities within PHC Re-engineering has been rolled out in various degrees of success, although provincial funding will have to be found and ring-fenced in order to effectively scale-up task-sharing innovations. In this vein, it should be noted that substantial inter-provincial differences emerged in terms of the weight of evidence produced (as found in an earlier analysis160), and strategies such as twinning teams from different provinces might enable critical skills transfer and promotion of mutual learning. Inter-sectoral collaboration is a common feature of public policy in South Africa, and arguably, mental health requires such collaboration more than other disease programmes due to the social nature of mental conditions. The Gauteng mental health system strengthening initiative proved to be a good example of enhanced out-patient and community care through “a district specialist mental health team to develop a public mental health approach, a clinical community psychiatry team for service delivery, and a team to support non-governmental organisation governance”.128(p538) Developing inter-sectoral platforms with real power to lobby for budgeting remains crucial in order to ensure a wider variety of stakeholders, including people with lived experience and their caregivers, and to provide mutual accountability to communities. Finally, the lack of an accurate picture of the burden of mental ill-health in South Africa will continue to hamstring strategising and budgeting, and regional epidemiological studies (not included in this review), along with robust indicators, ideally integrated with other conditions on a shared electronic registry, should be considered.

Recommendations

The following recommendations for important research and policy implementation are offered.

Research

-

Map and assess the adequacy of mental health infrastructure across provinces, with attention to space, staffing and accessibility.

-

Conduct intervention research and economic evaluations for community mental health services, prioritising participatory methods and co-creation to include marginalised and underserved groups.

-

Conduct implementation science studies for interventions shown to be effective in understanding how local leadership, organisational culture, and resource allocation influence service uptake and sustainability.

-

Explore scalable models for inter-sectoral collaboration between health, social development, traditional healers and NGOs, focusing on shared service plans and referral systems.

-

Explore effective strategies for overcoming barriers to policy participation among mental health service users.

-

Explore models supporting participatory governance and mutual accountability in the mental health system, including how to build capacity for local-level governance.

Policy and implementation

-

Develop formal structures for service user participation in policy-making and service design.

-

Redirect resources towards scaling-up community mental health interventions with appropriate South African evidence of effectiveness.

-

Prioritise sustained funding for psychosocial support and out-patient services for severe mental health conditions.

-

Prioritise leadership development for district and facility managers that focuses on mental health and incentivises mental health champions at all levels of the health system.

-

Implement national anti-stigma campaigns and integrate mental health literacy into education, justice, and social services.

-

Invest in digital infrastructure, training and regulatory frameworks that support the integration of digital mental health into community mental health services.

Conclusion

This integrative review is timely, marking three decades of research of mental healthcare in democratic South Africa. The conclusions emphasise both the advancements and the ongoing challenges in the country’s research landscape. While many notable strides have been made in developing and testing innovations across various levels of care, the reform aims of South Africa’s mental health system appears to have stagnated since previous assessments. The lack of investment in scalable interventions, within the context of a dearth of associated economic evaluations, continues to present a critical gap in helping to drive people-centred reforms. Future research should address these gaps as well as emphasising strong governance and leadership, intersectoral collaboration, more sustained partnership between researchers and implementers, and more meaningful inclusion of underserved marginalised groups into the research-policy-implementation-evaluation cycle. The goal of a mental health system that is people-centred, well-integrated, equitable, and effective in responding to the growing mental health needs of communities requires continual learning, prioritisation and investment, with sustained monitoring to ensure that these objectives are being met.

Acknowledgements

The valuable technical and academic input and support of Ms Alim Leung is gratefully acknowledged.