Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought crisis to healthcare systems globally. Surging waves of critically ill patients necessitated dramatic restructuring of healthcare facilities and massive internal redistribution of healthcare resources, which in the South African context were already stretched by an established quadruple burden of disease. The Western Cape recorded its first Coronavirus case on the 11th of March 2020, and rapid local progression of the pandemic resulted in the province experiencing the highest number of cases and deaths in the country during the initial period of the first wave in South Africa.

At Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH), a tertiary academic hospital linked to the University of Cape Town (UCT), the expanding disease burden displaced routine services due to the need for COVID-segregated in-patient care facilities, including high-care and intensive-care wards, and Operating Rooms (ORs). A motivation was therefore drafted by the hospital Chief Executive Officer, outlining the need for additional COVID-specific high-care beds, as well as COVID-specific ORs, to better meet this demand for urgent care of patients with COVID-19. A disused hospital space was proposed as the site for a 16-bed high-care ward for management of persons under investigation (PUI) and COVID-positive patients. In addition, two new ORs and a four-bed recovery area were built to process PUI and COVID-positive surgical emergencies. The infrastructure plan also included setting rooms, autoclaves, change rooms, a cold layout room, a sluice room, storage rooms, offices, sleep-in rooms, a staff kitchen, and rest areas.

However, with each successive wave many peri-operative staff were re-directed to critical-care services, while tertiary elective surgical care, already a crucial and scarce resource in the public sector, was de-escalated. These elective patients experienced progression of their primary disease and/or comorbidities while awaiting diagnostic workup and surgical procedures, and they subsequently required more complex and riskier procedures, resulting in higher complication rates and poorer outcomes.

Despite the name, ‘elective’ or ‘booked’ surgery is not optional, being necessary for curative care after diagnosis. At national level, the economic impact of delayed interventions was significant. Initially, curable early stage cancers eventually progress to stages of inoperability, with debilitating pain, shortened lifespans, and increasing cost of chronic cancer care. Benign conditions were also postponed. Both have the potential to impact on the quality of life of public-sector patients, their ability to work, earn an income, and care for themselves and their households.1–3 Reduced booked case numbers also decreases the number of experiential learning opportunities. This remains a threat to the clinical competence and quality of surgical care provided in the uninsured sector and can result in a loss of accreditation for reimbursement for such care in the insured sector.4–6

The global backlog of elective surgical cases after the first wave of the pandemic was estimated to be 30 million; this was calculated to take a year of operating time to work back, but only if all hospitals were to increase their pre-COVID surgical volumes by at least 20%.7 Data from six secondary hospitals in the Western Cape province showed that during the first wave, total surgeries decreased by 44%, and elective surgeries by 74%.8 At GSH, 1 500 theatre lists were foregone in the pandemic, resulting in the cancellation of approximately 10 000 elective surgeries.

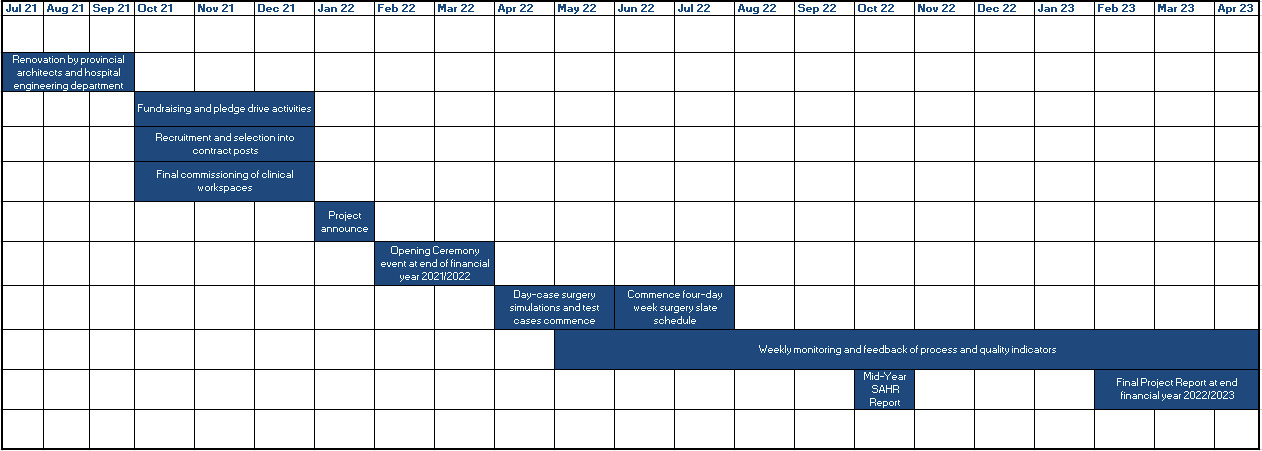

Despite all levels of the health system requiring increases in inputs so as to increase volume of surgical services, and despite the cost of services being relatively high at tertiary centres, it is these centres that have capacity for service escalation in the short term, in terms of staff, capital equipment and unused OR time, and therefore it is at this level that the greatest number of extra procedures can be accommodated. Accordingly, post-pandemic, the COVID-19 escalation space was envisioned as one of the sites for the Western Cape Surgical Recovery Project, specifically, the establishment of a fully-fledged Day-Case Surgery Suite, a service that had been planned for over a decade, pending funding. The proposal to utilise COVID-19 funding for this purpose was accepted by the Provincial Department of Health, and renovations were carried out by provincial architects and facility engineers for three months (from July to September 2021) with the receding of the first pandemic wave (Figure 1). A limited number of extra surgeries were allocated to smaller OR complexes at district and regional levels, while a mix of both complex in-patient and day-case procedures were performed at GSH.

The aim of this chapter is to describe the conceptualisation, planning, implementation and six-month mid-point results of the GSH Western Cape Surgical Recovery Project. The information is provided according to the six building blocks of the health system as espoused by World Health Organization Building Block model,9 and is based on the consolidated views of provincial management, facility management, and frontline clinicians.

The Groote Schuur Surgical Recovery Project

Financing

In March 2022, the Western Cape Deputy Director General of Health presented the Six Levers for Service Design Transformation post-COVID.10 This mapped out the recovery of services for: chronic diseases, intermediate care, violence and trauma, routine preventive services, equitable resource allocation, and as a distinct entity, surgical services. For this last service area, the Provincial Government allocated R20 million of its operating budget toward Surgical Recovery throughout the Western Cape, of which GSH and its referring hospitals (New Somerset Hospital, Victoria District Hospital and Mitchell’s Plain District Hospital) received R6.5 million to use for the staffing components of their respective peri-operative services.

One of the first independent organisations that GSH reached out to as a strategic funding partner was the Gift of the Givers Foundation (GOGF), the largest disaster-response non-governmental organisation based in Africa. Noting the systemic delays to access of urgent time-bound surgical services, an agreement was reached between GOGF and Hospital Management, for the organisation to assist with extra funding of the Provincial Department of Health’s Recovery Plan.11 GOGF pledged to commit a further R2.5 million per year over a period of two years. Funds were also donated by over 3 000 individuals, as well as social clubs and businesses.

Legal funneling and stewardship of these funds required the establishment of the GSH Trust as a Public Benefit Organisation (PBO) in 2021. The primary role of the Trust is to identify the most pressing unfunded service needs that do not fall within the allocated annual operational budget of the Hospital. The Trust has been active in fundraising and marketing and engaging with the public and helped the Project to gain greater community recognition through interactions and engagements with popular radio stations, participation in public events such as the Sanlam Cape Town Marathon, in which hospital staff and benefactors participated to raise funds. Supporters and the general public were updated regularly on the number of cases completed and they received patient case vignettes; this was done via GSH social media accounts and ongoing interaction with the formal media.

Medicines, technology, equipment and infrastructure

Upfront purchases included a full suite of capital equipment, including anaesthesia workstations, patient monitors, infusion and syringe pumps, ultrasound, difficult airway equipment, blood-gas analysers, defibrillators, electrocautery units, suction devices, autoclaves, computer terminals, and display and supply carts, among other items. As the area was designed for surgical and peri-operative care, isolated electrical outlets with generator backup, piped medical gasses and suction/scavenging, and suitable changing, cleaning and sluice areas, were included. When significant emergency funding became available during the pandemic, and as newer successful treatment modalities were demonstrated globally, the high-care specification infrastructure plans were then pivotable to include high-care-level treatment, including advanced monitoring and high-flow nasal oxygen-capable outlets at every bedside, and a staging area for the preparation, processing and sterilising of equipment for the hospital’s CAIR (COVID anaesthesia intubation and retrieval) team.12 Senior consultants were asked to vet all provincial equipment purchases (including video laryngoscopes, transport monitors and ventilators) both clinically and financially. This ensured cross-cutting functionality and lateral compatibility with existing equipment, cost-effectiveness, and regard for use in surgical service recovery post-pandemic.

Service delivery, leadership and governance

The Hospital’s Surgical Recovery Project was started in early May 2022, with extra hand surgery and eye cataract lists on Saturdays, using a mixed complement of GSH staff working overtime rates (for nursing staff) and pro bono (for medical staff), while recruitment and selection processes were initiated for formal posts. The project was implemented using a phased approach, gradually increasing the number of participating specialties. Day-case elective surgery was introduced first, followed by short-stay overnight cases, and finally more complex cases requiring longer stays.13 The rationale for this strategy of expanding ambulatory capacity first was to utilise fewer hospital resources and reduce risk of in-patient COVID exposure.2,14,15 Some surgical specialties, such as Cardiothoracic Surgery, Neurosurgery and Ophthalmology, were unable to make use of the Day-Case Surgery Suite, due either to lack of equipment or infrastructure constraints in the Suite. These specialties were provided with OR slates in Main Theatre in lieu of slates allocated to them for Surgical Recovery, and they used an extra staffing complement.

The Theatre Management Committee (TMC) at GSH, similar to other such Committees at the Hospital, maintains clinical and corporate governance of all peri-operative services provided in the Day-Case Surgery Suite, as well as the Main Theatre Complex overall. The Committee is a consultative and decision-making forum tasked with ensuring the maintenance of quality, safety, and efficiency; it is chaired by the Medical Manager: Peri-Operative Services, and includes senior surgeons, anaesthetists and theatre matrons. Transversal issues requiring further escalation, such as infrastructure maintenance and further equipment requisitioning, are relayed to the Hospital Executive Management Committee to action.

Human resources

Human Resources (HR) is a critical enabler of service (and cost) escalation. Staff costs generally account for two-thirds of all healthcare service expenditure, and this is a driver of other costs (for example, increased consumable utilisation); as such HR is tightly regulated.15,16 Despite this, there must still be contingency planning for when staff members are ill, or when emergency services are under pressure and requiring service escalation. Over the first financial year of operation (April 2022 to March 2023), expenditure for contract staffing (as well as high-cost consumables) was tracked by GSH cost centres for allocation and reconciling to the Surgical Recovery Project funds held with the hospital’s finance director. Purchase sign-off for requisitioned items is completed by the appropriately delegated individual, from Operational Manager to Medical Manager. At the end of the first financial year, permanent posts allocated are to be transitioned to the running of a Day-Case Surgery service, which will form part of the general expenditure of the Peri-Operative Services’ Functional Business Unit at the hospital.

Clerical support for the Surgical Recovery Project was required to manage information processing and administration of the unit. Information processing includes accurate and timeous capture of standard patient demographic, admission, procedure, quality, efficiency and discharge information onto the Hospital Information System. Thereafter, the hospital Information Management Unit (IMU) collates the captured information to create FBU reports detailing the volume, efficacy, quality and safety of the service provided. Efficient unit administration also involves folder management, assisting with the ordering of consumables and equipment, forwarding of patient billing information to the hospital accounting offices for fee payments, follow-up clinic bookings at Surgical Outpatient Department Clinics, and managing the schedule of the area OM.

A total of 14 full-time equivalent (FTE) nursing posts were created based on the requirement to run ORs for 12-hour day shifts (from 07h00 to 19h00, Monday to Thursday each week), the four-bed recovery area, and the 16 bed Day-Case Surgery Ward. Due to the lack of available theatre specialty-trained nurses, general nurses were employed for on-the-job upskilling. As most new staff had no prior theatre experience, half of the new nursing personnel were allocated to the Day-Case Surgery Suite and Ward, and half to more complex in-patient Surgical Recovery lists under supervision in the hospital’s Main Theatre Complex (MTC). This was done so that the nursing skills mix in the different ORs was balanced for the necessary training and supervision of junior staff to take place. Finally, a nursing OM was rerouted from the MTC, and managerial responsibilities in theatre were restructured in order to support the Surgical Recovery Project.

Two permanent anaesthetic registrar posts were created to process the increase in surgical workload. These staff are responsible for safely anaesthetising patients using either general or regional techniques, and also assist in outreach anaesthetic services, emergency transfer, and intensive care services at GSH. They are the primary clinicians responsible for pre-operative assessment and optimisation, as well as postoperative analgesia, recovery and discharge of patients. Anaesthetic consultants were rerouted from the existing pool to supervise and manage these registrars, to develop clinical protocols, to oversee the quality of care provided, and lead clinical governance of the Day-Case Surgery Suite. Clinical protocols and standard operating procedures (SOPs) developed and updated for the project included guidelines for referral to a pre-assessment clinic, pre-operative investigations required for day-case surgery, guidance on managing patients with common chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension and anaemia, general rules for pre-operative fasting, and analgesia guidelines for postoperative patients.

Two general surgeon Medical Officer (MO) posts were created to assist with the efficient processing of surgical recovery cases. These MOs were tasked with the support and management of peri-operative patients. This included liaison with the various surgical specialties on the hospital booking lists, assessment and work-up of patients pre-operatively, assistance intra-operatively, and safe discharge from the recovery area together with anaesthetic colleagues. In addition to process management of the area, the surgical MOs were also responsible for chairing daily morning multi-disciplinary OR huddles, ensuring that the data captured by clerical staff accurately reflected the caseload processed through the ORs, and taking part in weekly theatre-management meetings.

Information management

To fulfil the targets set by GSH in conjunction with the Province and external stakeholders, the TMC included volume, quality and efficiency measures of the new Day-Case Surgery Suite in the MTC FBU data reports, which are drawn by the Hospital IMU on a weekly and monthly basis. Generation of these reports requires accurate and timeous data transcription by theatre clerks, from nursing elective and emergency theatre registers, into proprietary cloud-based information systems such as Clinicom (for elective data) and WebSurgiBank (for emergency data).

Data are then extracted by the IMU and uploaded to the Hospital’s Microsoft SharePoint website. Data uploaded here are then visualised into Microsoft Excel charts and tables, as well as interactive dashboards using Microsoft Power BI. These data are used for both operational and formal research, having been authorised as a peri-operative registry with the UCT Human Research Ethics Committee. This enables a multi-disciplinary, team-based, data-driven approach to OR management, to deliver safe surgical services of a consistently high quality.

Results

The summary data below have been reviewed from official hospital datasets, as contained in the GSH Peri-Operative Registry.

Process

Elective waiting times for malignant and benign conditions were manually collated at the start of the Project, based on a survey of all Surgical Heads of Divisions. Just over 6 000 patients were waiting for surgical procedures at the start of the Surgical Recovery Project on the 1st of May 2022. This survey is planned to be repeated one year hence at the end of the first year of the Project.

From the start of May to the end of October 2022 (the first six months of the Project), a total of 800 surgical procedures were completed, averaging 133 procedures per month, or 31 procedures per week, and beyond the target of 750 procedures set for the period.

Specific ICD9 codes were utilised to record the types of procedures performed. Ranked by category, the largest number of procedures done were eye cases (n = 191), followed by cases involving surgery to the integumentary system (n = 141), and musculoskeletal system cases (n = 123).

There were a total of 30 patient cancellations on Surgical Recovery Project lists. Reasons for cancellation included patient issues (unwell for surgery, not starved, or did not attend on the day), or provider issues (lack of theatre time or equipment, or further workup required).

Efficiency

Start times over the first six months of the project were poor, with less than 10% of all theatre slates initially starting their first cases before 08h00. Despite poor on-time start (OTS) statistics in the first three months of operation (range 0.0 - 6.9%), the percentage of OTS improved markedly over the last few months of the Project (range 43.3 - 56.5%). While day-case surgery can decrease bed utilisation in hospital, this results in patients needing to travel to the hospital on the morning of their procedure, which introduces delays due to transport delays and folder administration.

Further difficulties experienced with day-case surgery include the necessary pre-operative assessment of patients and secondment of theatre equipment from Main Theatres. Lastly, at project start, emphasis was placed on safe, methodical daily start-up of the new OR slates, with less concern for efficiency initially.

The average duration of operations in the Surgical Recovery Project was 45 minutes, while the average duration including anaesthetic induction and recovery time was 80 minutes.

Quality

World Health Organization checklists have been completed for 85.1% of operations performed at the Day-Case Surgery Suite. No adverse incidents have been recorded against the Day-Case Surgery Suite. No 30-day in-patient mortalities have been recorded for the Project to date.

Discussion

Human resources

The greatest challenge to surgical recovery – at GSH, in the Western Cape, and nationally – is lack of trained nursing staff with the specialised skillset required to run ORs, despite there being funded posts vacant. Recruitment of staff in the public sector can also be a lengthy process, and in initiating the Project, Agency and Overtime expenditure had to be used. This is particularly difficult when trying to bring in nursing staff on ad hoc agency or very short-term contract conditions. Contracts were only filled several months after Project initiation. In future, provincial health department funding is likely to remain constrained. Thus, HR requirements are likely to be the main barrier to future service escalations.13,14

Future pandemic waves

Further challenges to surgical services remain the possible impact of future COVID waves, and lockdowns, especially if more virulent forms of the virus than Omicron resurface. The Day-Case Surgery Unit was used as a COVID-19 high-care space during the peaks of the COVID waves; in the event of future COVID waves, other high-care areas would need to be found to accommodate such patients in order to mitigate risk to the Project. However, de-escalation of Main Theatre Complex services would inevitably occur, due to the need for secondment of anaesthetic, nursing and surgical staff.

Although there have been attempts to devise and implement objective scoring systems (such as the MeNTS score and its local South African adaptations) to determine an adequate service mix between COVID and surgical services, surgical divisions at GSH found these impractical to use as a tool for deciding which cases to prioritise, given the considerable demand and backlog of surgical cases.16,17

Service needs for complex surgical cases

Despite the significant advantages of Day-Case Surgery, approximately half of all OR slates are planned to perform in-patient general anaesthesia procedures. Most surgical specialties at tertiary level perform operations that are not amenable to Day-Case Surgery, and have patients with longstanding, complex and advanced pathology. In-patient slates allowed these surgical teams to tackle the extremely long waiting lists at tertiary level, resulting from de-escalation of surgical services at GSH during COVID-19 waves. The number of beds available for pre-operative and postoperative care remain a constraint on tertiary-level surgical service escalation.

Evaluation challenges

Evaluation results show that the Surgical Recovery Project enabled increased surgical throughput and decreased surgical waiting time for patients; reduced ward bed occupancy through the use of a Day-Case Surgery model of care; reduced risk of in-hospital morbidity due to shorter hospital stays and enabled better multidisciplinary management of patients in a purpose-built space.

The evaluation process however was not without its pitfalls. Collection, collation and analysis of information across specialties is a time-consuming, manual and ad hoc process. Due to nuances in treatment algorithms and patient presentations, different specialties maintain their own waiting lists, with each diagnosis having its own target time from initial assessment to definitive surgical procedure. Patients are thus added and removed from these lists dynamically. Current provincial information systems do not cater to these varying needs, and there is no single database of patient waiting times for elective procedures, although theatre information systems are in development by the Western Cape Department of Health. These systems should be standardised across facilities and regions for comparative analysis.

Further complicating the use of elective waiting times for impact monitoring is the fact that prevalence of surgical illness is dependent on social determinants of health, the availability of effective screening programmes and referral systems, as well as population growth, particularly in urban areas.

Recommendations

In implementing the Project at GSH, it has been evident that the volume of services provided in the public sector can be escalated with the use of external funding of capital for HR, equipment and consumables. These services become truly effective when there is sufficient multi-disciplinary planning, alignment and support, at operational, strategic and executive levels of healthcare facilities. The following factors should be taken into account when undertaking similar initiatives.

-

A large outlay of capital investment is required for the delivery of peri-operative services. Therefore, a crucial enabler of peri-operative and critical-care services is access to the necessary funding for infrastructure and capital equipment. In the absence of such funding, network relationships of clinicians and managers within non-governmental organisations, corporate social investment schemes, tertiary institutions, charities and the general public can be leveraged through traditional media and social media to generate financial support. Active Hospital Trusts can perform this role, and the funding ambit of these institutions may increase over time, as tertiary provincial healthcare expenditure becomes more and more constrained.

-

Planning for short-term responses to external shocks to the health system, including future pandemic waves, must also consider future service demands, in order to channel unpredictable injections of funding into standing Annual Operational Plans, which can be readily actioned and provide the infrastructure skeleton on which future services can be built.

-

The use of provincial funding for such projects should be dedicated to the fixed-cost HR required (especially scarce nursing skills) to build service sustainability. Once-off or on-going purchases of variable-cost items such as equipment and consumables can then be requested from funders and declared as donated goods. There is a constant need to upskill and train staff, especially in scarce skills areas such as peri-operative services, hence this also needs to be built into staffing ratios. A benefit of this is the ability to employ lower-level staff, who can be upskilled in the process.

-

Data collection for monitoring and evaluation, as well as formal research, are crucial for understanding project progress, and should be built into routine unit management. Regular review meetings with Hospital Clerks and IMU personnel helps to facilitate standardised definitions and measurements. Hospital Information Systems, however, carry outdated and generic ICD coding dictionaries and require updating to the latest versions available. In the absence of this, regular data-verification meetings must be held between Clerks and Clinicians. Elective surgery wait-time monitoring systems need to be developed for facilities to review on a regular basis, and this can assist with dynamic theatre scheduling.

-

A mixed model of high turnover, centralised surgical services, together with partners in accessible peripheral hospitals, who are also able to make use of the same budget, can foster a sense of local Project ownership across the system. An increase in surgical procedures performed at regional and district level over the longer term would be a more cost-efficient use of resources.

-

An active and highly visible funding and media campaign can generate both financial and community support for healthcare facilities and is another opportunity to build trust with patient communities. Such a campaign can also galvanise the goodwill and dedication of staff around a common goal of increasing the general public good, despite multiple competing constraints faced by public healthcare services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Sasher Dayser for meticulous data entry for the Project; the Gift of the Givers Foundation and Hike2Heal for donations and support received; and Mrs Mary-Ann Dubru, Mr Aghmat Mahomed, Professor Justiaan Swanevelder, Professor Graham Fieggen, and Professor Salome Maswime for their support and guidance.